AP Syllabus focus:

‘Linkage institutions are channels that allow individuals to communicate their preferences to policymakers, including parties, interest groups, elections, and the media.’

Linkage institutions are the main “connecting tissue” between the public and government. They help citizens express preferences, help leaders interpret demands, and shape which voices and issues gain attention in policymaking.

What are linkage institutions?

Linkage institutions translate public preferences into political action by structuring participation, information, and communication between citizens and policymakers.

Linkage institutions: Channels that connect citizens to government by allowing people to communicate preferences and influence political outcomes (commonly political parties, interest groups, elections, and the media).

In practice, linkage institutions do three core things:

Transmit information upward (citizens’ concerns to leaders)

Transmit information downward (government actions and choices to citizens)

Organise participation (making collective action easier than acting alone)

The four major linkage institutions in AP Gov

Political parties

Political parties connect citizens to government by bundling (aggregating) many individual preferences into broader, recognisable policy brands.

They offer voters labels and cues that simplify choices.

They connect activists, donors, candidates, and officials into a shared network.

They create a pathway for citizen priorities to become governing agendas when a party wins office.

Key linkage idea: parties reduce the “translation problem” by turning scattered opinions into platforms and governing coalitions.

Interest groups

Interest groups connect citizens to policymakers by representing specific shared interests and pushing them into the policy process.

They provide specialised information to officials (data, expertise, policy proposals).

They signal intensity: even if a group is small, it may show that an issue is highly salient to its members.

They enable participation beyond voting through membership, donations, contacting officials, and public campaigns.

Key linkage idea: groups amplify organised interests, helping policymakers learn what attentive publics want—while potentially privileging those who can organise and sustain pressure.

Elections

Elections are a linkage institution because they create a recurring, rule-based mechanism for:

Citizen input (selecting leaders and approving or rejecting governing coalitions)

Accountability (rewarding or punishing incumbents)

Responsiveness (incentivising officials to anticipate voter reactions)

Elections link citizens and policymakers not only on Election Day but also through campaigns, debates, and issue messaging that reveal what politicians think the public will support.

Key linkage idea: elections are the clearest mass channel for preference expression, but the signals they send can be broad, indirect, and shaped by turnout and district rules.

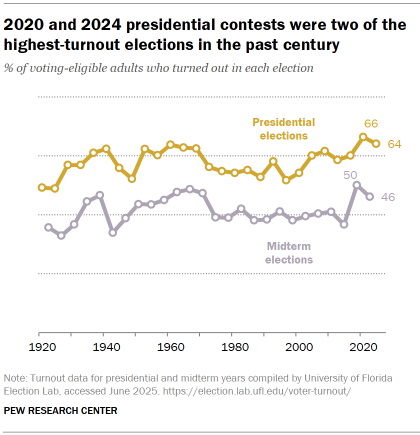

This chart tracks U.S. turnout in presidential and midterm elections across the past century, highlighting how citizen participation rises and falls over time. It helps illustrate why elections are a powerful but imperfect linkage channel: the “voice” government hears depends heavily on how many people show up. The high-turnout peaks (including 2020 and 2024) underscore how political context can amplify mass signals to policymakers. Source

The media

The media connect citizens and policymakers by shaping what the public knows and what leaders believe the public cares about.

They distribute political information and frame events for mass audiences.

They help set the public agenda by increasing attention to certain problems.

They act as a watchdog by highlighting misconduct or policy failures, raising reputational costs for officials.

Key linkage idea: the media are a two-way channel—citizens learn about government, and government learns what is gaining public attention.

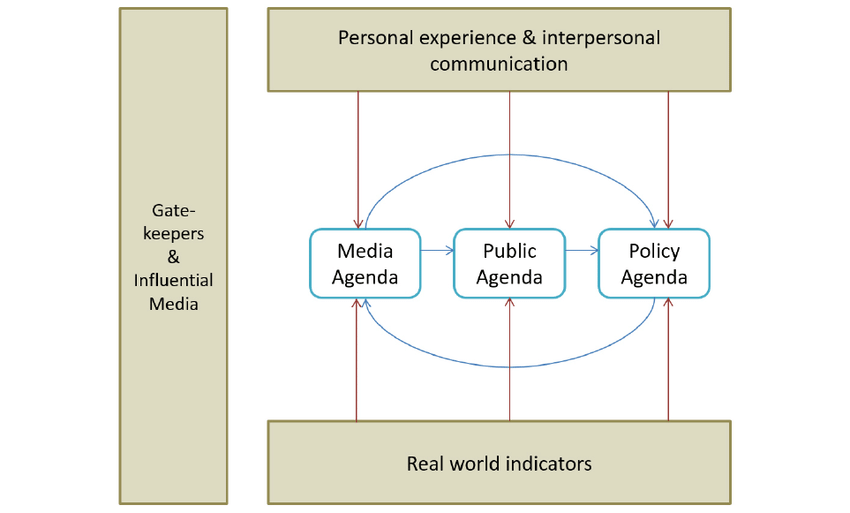

This diagram presents the classic agenda-setting framework by mapping relationships among the media agenda, the public agenda, and the policy agenda. It visually reinforces the idea that media attention can elevate issues on the public agenda and, in turn, influence what policymakers treat as urgent or politically relevant. The model also clarifies why “prioritisation” is a key linkage function: not all issues receive equal attention across these agendas. Source

How linkage institutions convert preferences into policy

Linkage institutions matter because government cannot respond to every individual opinion directly. They make public input “usable” by converting it into organised signals:

Aggregation: combining many views into clearer demands (often through parties or broad coalitions).

Articulation: expressing specific policy goals in concrete terms (often through interest groups and advocacy networks).

Prioritisation: elevating some issues above others (often through media attention and campaign agendas).

Accountability pressure: creating incentives for officials to adjust behaviour (especially through elections and sustained coverage).

Together, these channels shape what policymakers perceive as:

Majority preferences (what most people want)

Intense preferences (what mobilised groups care about most)

Urgent problems (what dominates public discussion)

Democratic strengths and limitations

Because linkage institutions organise participation, they can strengthen democracy by:

lowering information costs for citizens (party cues, news coverage)

providing regular opportunities to influence government (elections, advocacy)

enabling collective action (groups and party networks)

However, linkage institutions can also distort representation:

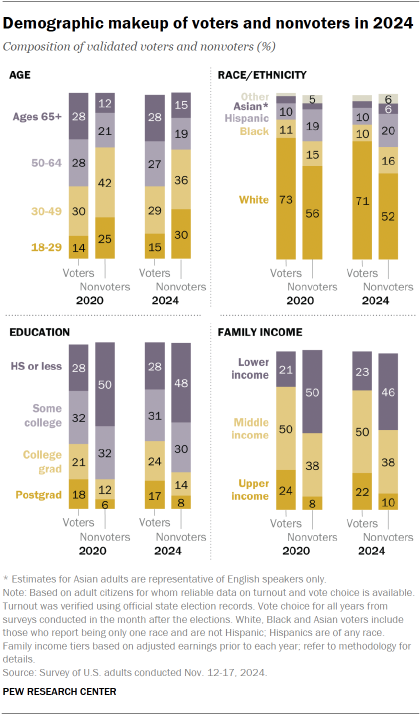

This figure compares the demographic makeup of voters and nonvoters, showing how participation differs by age, race/ethnicity, education, and income. It provides a visual way to understand how elections can transmit a filtered version of public preferences—especially when groups with fewer resources or lower engagement participate at lower rates. The chart also connects to debates about representation and responsiveness in a mass democracy. Source

Unequal voice: organised, well-resourced participants may be heard more clearly than disengaged or marginalised publics.

Selective responsiveness: policymakers may respond to high-salience media narratives or persistent group pressure even when broader public preferences are mixed.

Information problems: citizens may receive incomplete, biased, or strategically framed messages, weakening informed consent and accountability.

Understanding linkage institutions helps explain why public opinion does not automatically become public policy: the connection runs through intermediaries that filter, amplify, and reshape political demands.

FAQ

Linkage institutions are intermediaries that carry information and pressure.

Government institutions make and implement policy, while linkage institutions shape what government is pushed to do.

Yes.

Sustained networks (community coalitions, professional networks, activist circles) can function as linkage channels when they consistently transmit demands to officials.

Groups can signal intensity and persistence.

They also reduce policymakers’ information costs by supplying expertise and coordinated feedback that diffuse publics often cannot provide.

It can weaken monitoring of state and local officials.

With fewer dedicated reporters, information about routine governance may drop, reducing citizen knowledge and lowering accountability pressure.

Clarity, credibility, and reach.

Effective linkage channels deliver understandable signals, represent real constituencies, and maintain ongoing contact with decision-makers rather than one-off engagement.

Practice Questions

Define a linkage institution and identify one example. (3 marks)

1 mark: Correct definition: a channel connecting citizens and policymakers by communicating preferences.

1 mark: Identify one valid example (political parties, interest groups, elections, or the media).

1 mark: Briefly state how the example links citizens to policymakers.

Explain two ways linkage institutions connect citizens to policymakers, and analyse one limitation of relying on linkage institutions for democratic responsiveness. (6 marks)

2 marks: First way explained (e.g., elections create accountability and incentives to respond).

2 marks: Second way explained (e.g., media sets agenda/transmits information; or interest groups provide issue signals).

2 marks: One limitation analysed (e.g., unequal access/resources, distorted issue priorities, or biased/incomplete information) with clear link to responsiveness.