AP Syllabus focus: ‘Political parties mobilize and educate voters, helping people participate and make choices in elections.’

Political parties try to win elections by turning supporters into actual voters and by giving people information shortcuts about candidates and issues. Mobilisation and education strategies shape who participates and how they vote.

What it means to mobilise and educate

Political parties act as linkage institutions by connecting citizens to government through elections.

This photograph documents a 1935 voter outreach setting in which party-aligned organizers use posters and face-to-face instruction to teach potential voters how to participate. It illustrates how parties (and allied groups) combine mobilization (bringing people into the electorate) with education (providing simple, visible cues about candidates and partisan commitments). Source

In practice, that means two related tasks:

Mobilising voters: increasing turnout and participation among likely supporters.

Educating voters: providing cues about issues, candidates, and stakes so voters can make choices.

Parties do both because many Americans have limited time and information, and because turnout is uneven across groups and elections.

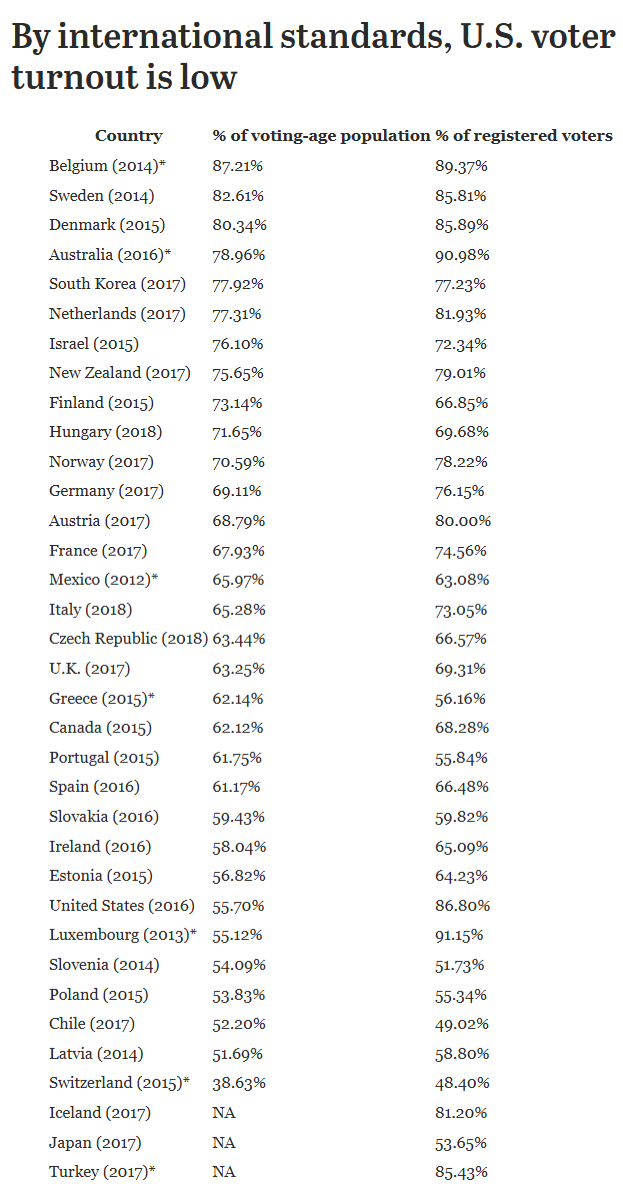

This Pew Research Center chart compares voter turnout across democracies, showing that U.S. turnout is relatively low by international standards. The visualization helps explain why parties invest heavily in turnout operations: when baseline participation is modest, targeted mobilization can meaningfully change who shows up—and therefore who wins. Source

Core concept: GOTV

Get-out-the-vote (GOTV): party efforts close to an election to increase turnout among identified supporters through reminders, assistance, and direct contact.

GOTV is often decisive in lower-turnout contexts, where small changes in participation can change results.

How parties mobilise voters

Parties mobilise by reducing costs of voting (time, confusion, access) and increasing the perceived benefits (importance, group identity, competition).

Direct contact and ground game

High-impact mobilisation typically involves repeated, personal outreach:

Door-to-door canvassing to identify supporters and encourage turnout

Phone banking and texting to remind voters about registration, dates, and locations

Rides to the polls and help locating polling places or ballot drop boxes

Volunteer recruitment through local party organisations and campus/community networks

Face-to-face contact is resource-intensive, so parties concentrate it where it is most likely to matter (competitive districts, swing precincts, high-propensity supporters).

Data-driven targeting

Modern party organisations rely on voter files and analytics to prioritise outreach:

Segmenting voters by likelihood to support the party and likelihood to turn out

Tailoring messages (jobs, education, safety) to different audiences

Tracking contacts to avoid duplication and to focus on persuadable or low-turnout supporters

Targeting helps parties allocate limited time and volunteers, but it can also mean some communities receive less outreach if they are viewed as electorally “safe” or “unwinnable.”

Mobilisation through identity and social networks

Parties also mobilise indirectly by shaping social incentives:

Using partisan identity and group-based appeals (“people like you are voting”)

Encouraging participation through unions, churches, student groups, and community leaders aligned with the party

Leveraging endorsements and local surrogates to build trust

How parties educate voters

Parties educate by creating clear, consistent signals about what a vote means. This matters because ballots can be complex and because many voters rely on cues rather than detailed policy study.

Information shortcuts and issue framing

Parties provide heuristics (informational shortcuts) through:

Party labels on ballots that indicate general ideology and policy direction

Talking points that highlight which issues the party wants voters to prioritise

Comparisons that frame choices as consequences (taxes, rights, services)

Education is not neutral: parties highlight favourable information and downplay weaknesses, aiming to define both their candidates and their opponents.

Voter education tools

Common educational methods include:

Sample ballots and voter guides shared online and through mailers

Candidate events, town halls, and speeches that explain priorities

Digital content (short videos, infographics) designed for rapid consumption

Rapid response messaging to interpret breaking events in partisan terms

These efforts can increase political knowledge for engaged citizens, but can also contribute to selective exposure where voters mainly hear one side.

Why mobilisation and education matter for participation

Mobilisation and education influence participation by shaping:

Turnout: reminders, social pressure, and assistance raise the likelihood of voting.

Choice: party cues help voters connect broad values to candidate selection.

Political engagement: repeated contact can bring new participants into volunteering, donating, and community action.

Parties are most effective when they combine education (clear stakes and cues) with mobilisation (concrete steps to participate).

FAQ

They often rank voters by likelihood to support the party and likelihood to turn out, then prioritise “low-turnout supporters” because they are easiest to convert into additional votes.

In-person contact can build trust, allow two-way conversation, and create stronger social pressure to follow through, especially when done by local community members.

They may use randomised field experiments (A/B tests) comparing turnout rates between contacted and non-contacted groups, then scale up the most effective scripts.

In highly polarised environments, fewer voters are persuadable, so increasing participation among existing supporters can be more efficient than changing minds.

Local organisations provide neighbourhood knowledge, volunteer networks, and relationship-based outreach, while national groups supply data, messaging templates, and coordinated campaign support.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks) Explain one way political parties mobilise voters.

1 mark: Identifies a valid mobilisation method (e.g., canvassing, phone banking, texting reminders).

1 mark: Describes how it increases turnout (e.g., reminders, assistance, social pressure).

1 mark: Connects to targeting supporters/raising participation close to election day.

Question 2 (4–6 marks) Analyse how political parties educate voters and how that can affect voter choice.

1 mark: Defines or accurately describes voter education as providing cues/information about candidates/issues.

1 mark: Explains a tool (party labels, voter guides, messaging, endorsements).

1 mark: Explains how cues act as heuristics that shape vote choice.

1 mark: Discusses issue framing/agenda emphasis influencing what voters consider important.

1 mark: Notes a limitation or consequence (selective exposure, biased information, uneven outreach).

1 mark: Uses clear, accurate political knowledge and links education to electoral decisions.