AP Syllabus focus:

‘Winner-take-all voting districts create structural barriers to third-party and independent candidates and advantage the two-party system.’

Winner-take-all election rules shape how votes translate into power, influencing which parties compete and win. In the United States, these rules reward broad coalitions and penalise smaller parties, reinforcing two-party dominance.

Core idea: how winner-take-all shapes party competition

Winner-take-all rules create a seat “bonus”

In many U.S. elections, the candidate with the most votes wins the entire office for that district or state. This differs from systems that distribute representation across multiple parties.

Winner-take-all election: An electoral rule in which the candidate (or party slate) with a plurality or majority wins the single available seat, and all other votes do not earn representation.

Winner-take-all rules matter because they determine whether a party’s support becomes governing power. Even substantial minority support can produce zero seats if it is spread across districts rather than concentrated.

Single-member districts and plurality voting

Most U.S. legislative elections use single-member districts (one seat per district) and often a plurality standard (most votes wins). Together, these rules:

discourage multiple viable parties from competing for the same ideological space

make it hard for smaller parties to convert votes into seats

raise the “threshold” of support needed to win anything at all (a seat)

Why third parties struggle under winner-take-all

The mechanical effect: translation of votes into seats

Winner-take-all systems create a direct structural barrier: representation is not proportional to vote share.

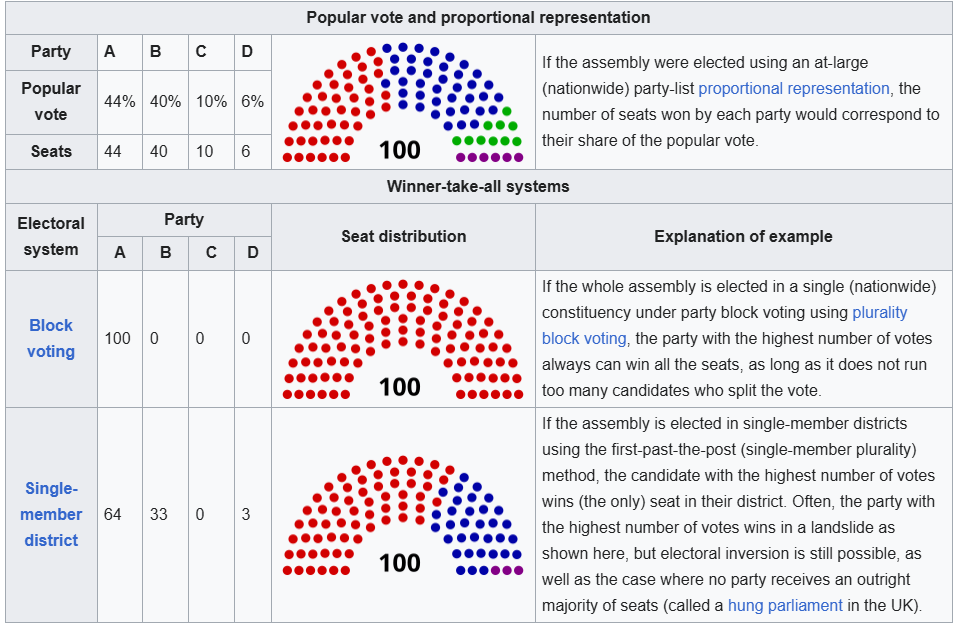

This table/figure contrasts proportional representation with winner-take-all outcomes, showing how a party’s seat share can diverge from its vote share under single-member plurality rules. It visually demonstrates the “seat bonus” for larger parties and how smaller parties can receive meaningful vote shares yet win few or no seats. Source

A third party can win 10–20% across many districts and still win 0 seats.

Major parties can receive a seat advantage from modest pluralities because winning by 1 vote yields the same seat as winning by 20 points.

This mechanical effect encourages politics to consolidate around two large parties that can realistically finish first.

The psychological effect: strategic behaviour by voters and elites

Winner-take-all rules also change incentives and expectations.

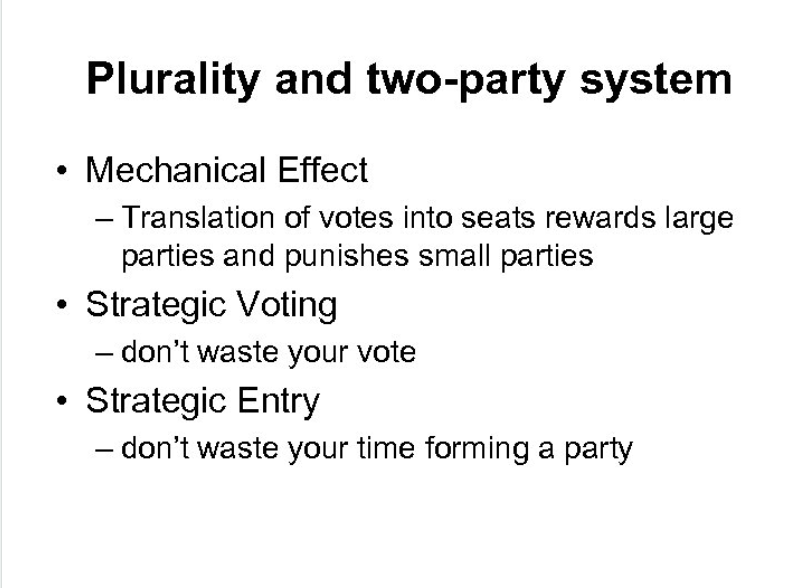

This diagram summarizes how plurality, single-member (winner-take-all) elections produce two-party competition through a mechanical effect (votes-to-seats translation favors large parties) and strategic behavior (voters and candidates avoid “wasting” effort on likely losers). It provides a compact visual bridge between Duverger’s law and strategic voting/entry. Source

Voters often avoid “wasting” a vote on a candidate unlikely to win and instead choose the major-party candidate closest to their preferences (strategic voting). Candidates, donors, activists, and media outlets likewise tend to:

treat third-party bids as spoilers rather than contenders

direct resources towards the two parties most likely to win

push ambitious politicians to run within a major party rather than against both

Duverger’s law: A political science generalisation that single-member, plurality (winner-take-all) elections tend to produce a two-party system, largely through mechanical and psychological effects.

How winner-take-all advantages the two parties

Coalition-building happens inside major parties

Because only one candidate can win each office, groups with different priorities have incentives to combine into broad electoral coalitions. In the U.S., coalition bargaining tends to occur within the Democratic and Republican parties rather than across many separate parties.

This advantage shows up in:

recruitment of candidates with broad appeal rather than narrow platforms

party branding that signals a “governing alternative” to the other major party

pressure on factional movements to work through primaries, endorsements, and party networks instead of launching separate parties

“Spoiler” dynamics reinforce two-party choices

When a third-party candidate draws votes from a major-party candidate with similar supporters, it can change the winner even if the third party has no path to victory. Anticipation of this effect:

discourages third-party voting among risk-averse voters

encourages major parties to appeal to voters who might defect to a minor party

frames elections as binary choices, especially in competitive districts and swing states

Institutional reinforcement beyond districts

Winner-take-all is not only about districts; it is also reflected in broader electoral practices that often award all representation to the top finisher in a jurisdiction (for example, many statewide contests for single offices). These rules amplify the perception that only two competitors are viable.

FAQ

Yes. Signature requirements, filing fees, and varying state rules can raise the cost of entry.

They interact with winner-take-all by forcing minor parties to spend resources just to appear on ballots, even before overcoming the “finish first” hurdle.

Fusion voting allows more than one party to nominate the same candidate, combining vote totals.

It can reduce the spoiler problem by letting minor parties demonstrate support without splitting the vote, but it is banned in most states.

Local races may have weaker party competition, lower information costs, and candidate-centred voting.

A third party can also win if its support is geographically concentrated or if a major party is organisationally weak in that locality.

RCV keeps single-winner seats but changes incentives by allowing preference ranking.

It can reduce strategic voting and spoiler effects, potentially making minor-party candidacies more viable without guaranteeing proportional representation.

Independents must still finish first to win a single seat and often lack party infrastructure.

They may also struggle with fundraising, media coverage, and building a durable coalition across multiple elections.

Practice Questions

(2 marks) Explain one way winner-take-all elections advantage the two-party system.

1 mark: Identifies a valid way (e.g., disproportional seat outcomes, strategic voting, spoiler effect).

1 mark: Explains how that mechanism benefits two major parties (e.g., small parties win votes but no seats, voters abandon minor parties to avoid wasting votes).

(6 marks) Analyse how winner-take-all electoral rules create structural barriers for third-party and independent candidates in the United States.

1 mark: Defines or accurately describes winner-take-all/single-member plurality rules.

2 marks: Explains the mechanical effect (votes-to-seats disproportionality; high threshold to win any representation).

2 marks: Explains the psychological effect (strategic voting; donors/candidates/media focus on viable major parties; spoiler concerns).

1 mark: Links these effects to sustained two-party dominance (coalitions form within major parties; third parties struggle to persist).