AP Syllabus focus:

‘Parties use communication technology and voter data management to shape messages, expand outreach, and mobilize supporters.’

Modern political parties rely on digital communication and data-driven targeting to compete in candidate-centred elections. These tools help parties tailor messages, find persuadable voters, and coordinate turnout operations efficiently across many platforms.

Communication technology in party strategy

Parties use communication technology to deliver information quickly, repeatedly, and in customised formats that fit different audiences and media habits.

Key technologies and channels

Campaign websites and email lists to collect supporter information and deliver updates, donation asks, and volunteering opportunities.

Text messaging (SMS) and peer-to-peer texting to push reminders, event details, and rapid responses near Election Day.

Social media platforms for short-form messaging, shareable content, livestreams, and influencer-style amplification.

Digital advertising (search ads, display ads, streaming audio/video ads) to reach specific audiences based on interests, location, and online behaviour.

Collaboration tools (volunteer apps, phone-banking platforms, virtual events) to coordinate large-scale mobilisation with less central staffing.

What communication technology allows parties to do

Shape messages by adapting language, tone, and issue emphasis to different segments of the electorate.

Expand outreach by contacting voters at lower cost than traditional mail or broadcast television.

Mobilise supporters through reminders, social pressure cues, and easy “one-click” paths to donate, volunteer, or attend events.

Voter data management

Communication becomes more effective when parties can decide who should receive which message and when. That requires ongoing voter data management.

Core data sources parties manage

Voter files (state-provided registration and turnout history) that form the backbone of targeting.

Consumer and lifestyle data (purchased or modelled) used to infer interests or likely priorities.

Digital engagement data (email opens, website visits, ad clicks) used to measure responsiveness.

Field data from canvassing and phone calls (issue concerns, support levels, volunteer interest).

Turning data into strategy

Parties integrate and update data to:

Identify base voters (reliable supporters), persuadables (reachable swing voters), and low-propensity supporters (need mobilisation).

Prioritise scarce resources (staff time, volunteer calls, advertising money) toward voters most likely to affect outcomes.

Adjust messaging based on real-time feedback (what content attracts attention or prompts action).

Microtargeting and tailored messaging

Parties use data to customise appeals rather than relying on a single, broad message for all voters.

Microtargeting: the use of detailed voter data and predictive analytics to send tailored political messages to narrow, specific groups of voters.

Issue targeting (emphasising different issues to different audiences).

Turnout targeting (focusing on supporters who need reminders or assistance to vote).

Channel targeting (choosing the most effective platform for each voter group).

Mobilisation and turnout operations (GOTV)

Data and technology are especially important for get-out-the-vote (GOTV) efforts, when timing and coordination matter most.

How parties use tech to mobilise supporters

Create lists for door-knocking, calls, or texts based on likelihood of support and turnout.

Send location-specific voting information (polling place changes, early voting sites, deadlines).

Track contact attempts and outcomes to avoid duplication and to re-contact high-priority voters.

Coordinate volunteers rapidly, including remote phone banks and distributed texting teams.

Limits, trade-offs, and democratic implications

Technology and voter data management can strengthen party capacity, but they also raise concerns tied to how parties communicate and compete.

Information quality risks: fast-moving online ecosystems can reward simplistic or misleading content, and targeted messages may be less visible to public scrutiny.

Privacy and trust concerns: extensive data collection can make voters feel monitored, reducing confidence in parties or the electoral process.

This diagram summarizes the major functions in a privacy risk management program: Identify, Govern, Control, Communicate, and Protect. It helps explain why parties’ large-scale voter data practices can trigger concerns about oversight, consent, and safeguards. The figure is useful for connecting campaign data use to broader debates about privacy governance and public trust. Source

Fragmented messaging: highly segmented appeals can make party platforms feel inconsistent across groups, complicating accountability.

Digital divides: unequal access to reliable internet or digital literacy can make outreach less effective for some communities, affecting participation.

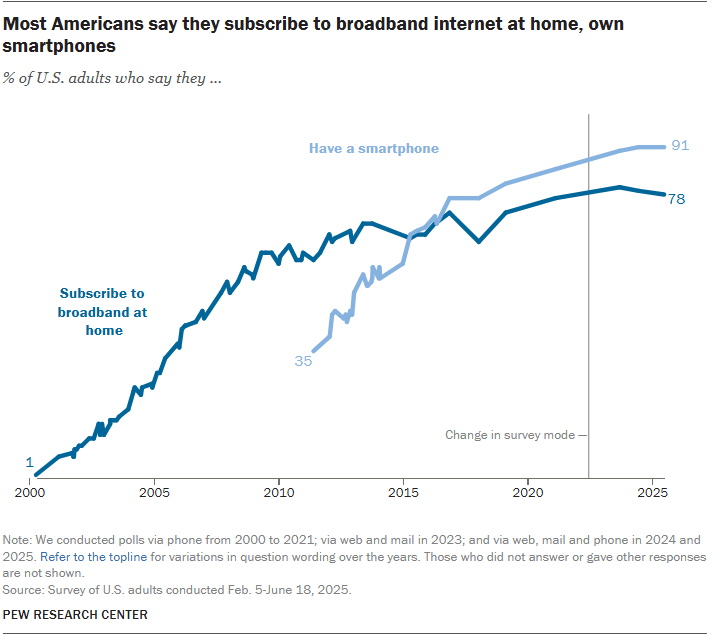

This Pew Research Center chart tracks U.S. adults’ access to key digital infrastructure (especially home broadband), providing concrete evidence that access is widespread but not universal. It supports the idea that digital-first party outreach can systematically underreach groups with lower connectivity. Using this kind of data helps distinguish campaign strategy claims from measurable participation constraints. Source

FAQ

They use data matching (often via vendors) to link records with probabilistic methods.

Common matches: name, address, date of birth, device identifiers

Outputs include “confidence scores” for whether two records are the same person

A/B testing compares two versions of a message to see which performs better.

It commonly measures click-through rates, sign-ups, donations, or time spent on a page, helping parties refine wording and images.

They are groups generated by platforms to resemble an existing list of supporters.

Parties use them to expand outreach to new but similar users when they lack direct voter contact information.

Key risks include phishing of staff accounts, ransomware, and data leaks from vendors.

Mitigation typically involves multi-factor authentication, access limits, encryption, and strict vendor security requirements.

Rule changes can restrict targeting options, political ad formats, or data access.

Algorithm shifts can also reduce organic reach, forcing parties to rely more on paid ads, email lists, and direct texting to maintain contact frequency.

Practice Questions

Define microtargeting and describe one way a political party might use it to mobilise supporters. (3 marks)

1 mark: Accurate definition of microtargeting (data-driven targeting of narrow voter segments with tailored messages).

1 mark: Describes a mobilisation use (e.g., targeted turnout reminders, volunteer recruitment, early voting prompts).

1 mark: Links the use to supporter mobilisation (increasing likelihood of voting/participating).

Analyse how communication technology and voter data management have changed how parties shape messages and expand outreach. In your answer, explain one benefit and one drawback for democratic participation. (6 marks)

2 marks: Explains message shaping/outreach changes (e.g., tailored digital ads, rapid-response messaging, multi-platform distribution, prioritising persuadable/low-propensity voters).

2 marks: Explains voter data management’s role (e.g., voter files + analytics to segment, allocate resources, track contacts).

1 mark: Clear benefit for participation (e.g., easier mobilisation, more relevant information, lower-cost outreach increasing contact).

1 mark: Clear drawback for participation (e.g., privacy concerns, misinformation/low transparency, fragmented messaging reducing accountability).