AP Syllabus focus:

‘National culture developed alongside continued regional variations, reflecting differences in economy, politics, and social life across the new republic.’

Regional differences in economy, politics, society, and culture persisted after independence, shaping competing visions for the nation’s future and challenging efforts to create a unified American identity.

Regional Variations and Competing Visions

Economic Foundations and Divergent Regional Priorities

Regional identity in the early republic emerged largely from distinct economic structures that shaped daily life and political expectations. The Northeast, increasingly commercial and maritime, relied on shipbuilding, trade, and early manufacturing.

These activities encouraged support for policies that protected commerce, strengthened the national economy, and ensured federal regulation of trade. By contrast, the South depended heavily on agriculture, particularly plantation-based cash crops such as tobacco, rice, and cotton. This agricultural orientation promoted a preference for minimal federal interference, low tariffs, and policies that protected slavery.

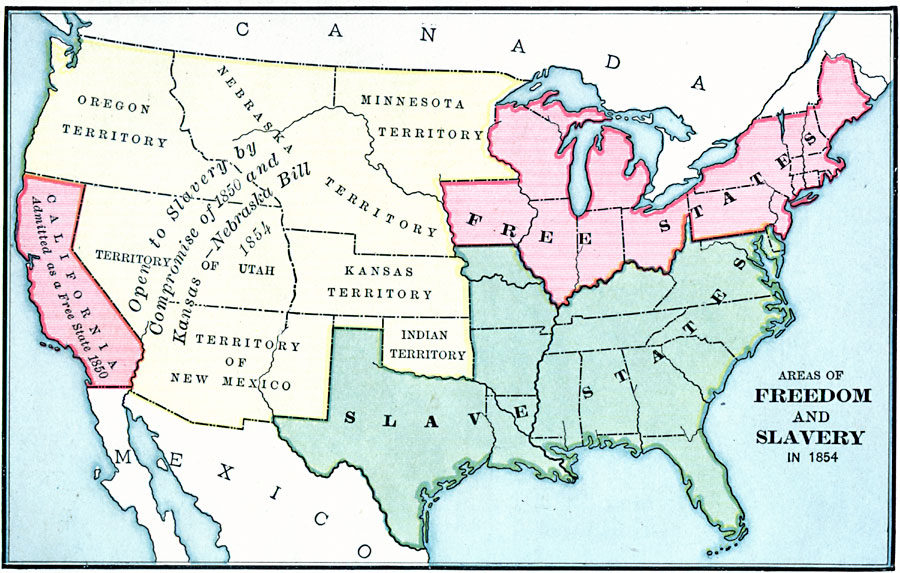

This map shows free states, slave states, and territories open to slavery in 1854, highlighting a sharp sectional division between regions grounded in different labor systems and economic interests. It helps students connect southern support for slavery-protective policies and northern opposition to the expansion of slavery to broader patterns of regional variation and competing visions for the nation. The map includes details tied to the Kansas–Nebraska Act and mid-19th-century territorial politics, extending beyond Period 3 but illustrating long-term consequences of earlier regional differences. Source.

The West, consisting of frontier territories beyond the Appalachians, prioritized land access, infrastructure, and security from Native nations and foreign powers. Its residents often demanded federal support for transportation networks and protection of migratory rights.

These distinct economic worlds fostered divergent expectations about the role of government. Northeastern merchants favored a stronger central government to encourage stable credit and economic growth, while Southern planters feared centralized authority could threaten local power and enslaved labor systems. Western settlers sought representation and federal investment but remained skeptical of elite-controlled institutions.

Social Structures and Regional Identity

Social differences across regions reinforced competing visions of American society. The hierarchical social system of the South rested on plantation wealth and the institution of slavery, producing sharp class distinctions and a political culture dominated by elite landowners.

Enslaved people harvest cotton on a Mississippi Valley plantation under white supervision, illustrating how coerced labor sustained the southern plantation economy. The scene reflects the unequal social order in which enslaved workers produced the wealth that empowered a small elite of slaveholding landowners. Although dated 1857, it depicts plantation structures and labor relations foundational to southern society since the early republic. Source.

In contrast, the North exhibited a more diverse social order characterized by small farmers, artisans, merchants, and wage laborers. Though inequality persisted, social mobility was more pronounced, shaping a culture that valued industriousness and civic participation.

The frontier West developed a reputation for relative egalitarianism, shaped by settler migration, cultural blending, and the practical demands of frontier life. These conditions encouraged a suspicion of entrenched hierarchies and contributed to a political culture that emphasized personal independence and broad access to property ownership.

Political Culture and Competing Visions of the Republic

Political visions in the early republic reflected these regional contrasts. Northeastern Federalists, influenced by commercial and urban interests, supported a political order that balanced popular participation with institutional checks. Their vision emphasized economic development, national authority, and diplomatic stability. Southern and western Democratic-Republicans, led by Jefferson and Madison, advocated an agrarian republic grounded in the independence of small farmers. This vision stressed decentralized authority, limited federal power, and protection of liberties from potential governmental overreach.

Agrarian Republic: A political vision asserting that a nation of independent farmers provides the best foundation for liberty, civic virtue, and minimal centralized authority.

These ideological differences were not simply philosophical; they reflected lived experience. Southern elites feared policies that favored northern commerce, while northern merchants worried that southern agricultural dominance threatened national economic coherence. Western residents viewed both coastal regions as disconnected from frontier concerns, fueling demands for increased political voice.

A sentence here ensures spacing between definition blocks.

Cultural Expressions of Regional Distinctiveness

Regional variations appeared in literature, religious practices, and local customs. The Second Great Awakening spread at different rates, gaining strong influence in frontier and southern regions where revivalist preachers appealed to local conditions and social needs. Northern communities often blended religious revivalism with reform movements, creating a distinctive culture that linked faith with social improvement.

Art, newspapers, and local histories also expressed regional pride. Northeastern writers emphasized maritime heritage and republican virtue, while southern authors celebrated rural life and hierarchical order. Western storytellers and travelers’ accounts depicted frontier resilience and opportunity, shaping a cultural mythology of expansion and self-reliance.

Regional Tensions Within a Growing National Culture

Despite these differences, Americans increasingly imagined themselves as part of a national political community. Symbols such as the American flag, public ceremonies, and shared Revolutionary memory contributed to a broader national culture. Yet regional voices shaped how this national identity was interpreted. Northerners linked national destiny to commerce and industrial development; Southerners associated it with agrarian independence and the preservation of social order; Westerners envisioned a nation defined by expansion and democratic access to land.

These contrasting visions illuminated ongoing debates over federal authority, economic policy, and cultural development. Regional variations did not prevent nation-building, but they ensured that American identity remained dynamic, contested, and deeply influenced by local circumstances.

FAQ

Geography shaped economic possibilities, which in turn influenced cultural and political expectations.

The North’s natural harbours and shorter growing season encouraged trade and small-scale farming, supporting commercial communities.

The South’s fertile soil and long agricultural seasons enabled plantation agriculture and reinforced hierarchical structures.

In the West, abundant land and sparse settlement fostered independence, mobility, and a more fluid social order.

Frontier settlers believed coastal elites did not understand the challenges of life beyond the Appalachians.

Key sources of distrust included:

• Limited federal protection from conflict with Native nations.

• Weak infrastructure investment reaching frontier communities.

• Perceptions that eastern politicians prioritised commercial or plantation interests over western land claims.

Movements of people carried regional cultures into new areas.

Southerners migrating westward brought slave-based agriculture with them, raising debates about slavery’s expansion.

Northerners relocating to new towns often reproduced more egalitarian social structures, heightening contrasts with neighbouring regions.

These migrations spread regional ideas across contested spaces, sharpening national disputes.

Northern regions often linked religious revivalism to social reform, reinforcing visions of a moral, participatory civic culture.

Southern religious life tended to emphasise personal salvation and social order, aligning with hierarchical regional norms.

Western revivalism embraced spontaneity and emotional preaching, encouraging a more populist vision of national identity.

Improved roads, postal routes, and print circulation spread information unevenly.

The North, with dense towns and transport links, developed faster-moving networks that supported commercial coordination and political mobilisation.

Southern rural dispersion slowed communication, reinforcing localism and elite dominance.

Western communities, often isolated, relied on oral exchange and itinerant preachers, strengthening frontier identity and scepticism toward distant authority.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Explain one way in which economic differences between the Northern and Southern regions shaped competing political visions in the early American republic.

Question 1

1 mark

• Identifies a relevant economic difference (e.g., Northern commerce vs. Southern plantation agriculture).

2 marks

• Explains how this economic difference influenced a political viewpoint (e.g., Northern support for a strong central government to regulate trade; Southern preference for limited federal authority to protect slavery and agricultural interests).

3 marks

• Provides specific and accurate detail tying the economic difference to a broader political vision (e.g., Federalist economic development policies vs. Democratic-Republican agrarian ideals) and clearly links regional priorities to political conflict or debate.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Analyse how regional social structures contributed to differing ideas about national identity in the early American republic. In your answer, refer to at least two regions.

Question 2

4 marks

• Describes regional social structures in at least two regions (e.g., Northern social mobility and diverse labour systems; Southern hierarchy based on slavery; Western frontier egalitarianism).

• Shows general understanding of how these structures shaped ideas about national identity.

5 marks

• Clearly explains how social structures influenced differing conceptions of what the nation should be (e.g., Northern emphasis on civic participation and reform; Southern defence of hierarchy; Western emphasis on independence and expansion).

• Uses well-chosen, relevant detail to support the argument.

6 marks

• Offers a sustained and coherent analysis that directly links social structures to contrasting visions of national identity.

• Demonstrates nuanced understanding of how these differences created tensions within emerging national culture.

• May include precise examples (e.g., differing attitudes toward government authority, liberty, or democratic participation) that show depth of knowledge.