AP Syllabus focus:

‘Revolutionary-era awareness of inequality led some groups to call for abolition of slavery and for greater political democracy in state and national governments.’

Growing revolutionary ideals of liberty, equality, and natural rights pushed Americans to confront glaring social inequalities, prompting debates about slavery and political participation during the nation’s founding years.

Growing Awareness of Inequality in the Revolutionary Era

The era of the American Revolution generated unprecedented discussions about the contradiction between the colonies’ fight for liberty and the persistence of social and political inequality. Revolutionary arguments emphasizing natural rights, popular sovereignty, and republican virtue encouraged many Americans to examine the legitimacy of existing hierarchies. This relationship between ideology and social change created new debates about the place of slavery, citizenship, and rights in the emerging nation.

Enlightenment Thought and Revolutionary Ideals

Enlightenment philosophies that influenced the Revolution—especially the writings of John Locke, who emphasized natural rights to life, liberty, and property—encouraged colonists to view freedom as a universal entitlement. Many reformers drew on these ideas to argue that slavery, defined as the ownership of one person by another and the denial of individual liberty, violated essential republican principles.

Slavery: A system in which individuals are legally considered property and denied personal freedom, labor autonomy, and natural rights.

These Enlightenment-infused arguments prompted moral questioning across the colonies, especially in regions where slavery was less economically entrenched.

Calls for Abolition of Slavery

Growing ideological tension between liberty and bondage inspired early abolitionist sentiment. While slavery remained deeply rooted in the plantation economies of the South, several developments fueled antislavery movements across the North.

Revolutionary Rhetoric and Moral Challenge

Patriot leaders’ claims that “all men are created equal” exposed contradictions in a slaveholding society. Enslaved people themselves invoked revolutionary language in petitions, legal suits, and escape attempts, asserting their right to freedom. White reformers, religious leaders, and Black activists increasingly questioned the moral basis of human bondage.

Regional Actions Toward Emancipation

Northern states became the center of early antislavery reform because their economies relied less on enslaved labor.

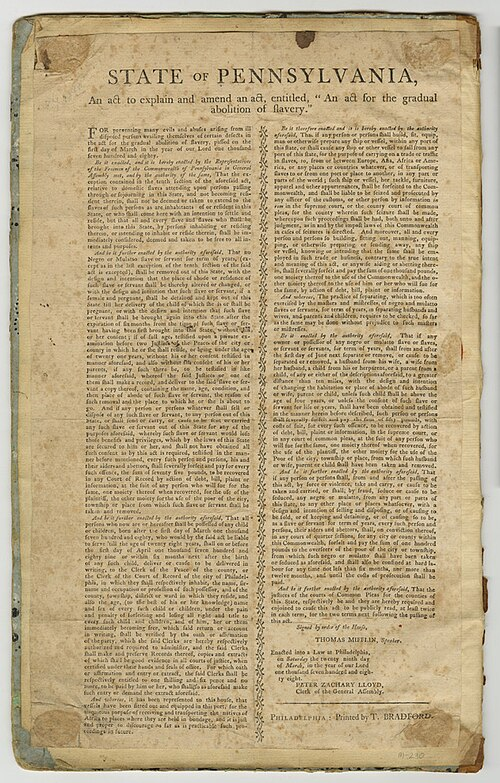

Printed broadside of Pennsylvania’s act “for the gradual abolition of slavery,” explaining and amending the landmark 1780 law. The document shows how early antislavery reforms were implemented through detailed state legislation rather than immediate emancipation. The broadside includes more legal detail than required by the syllabus, but it clearly illustrates how Revolutionary-era governments began to challenge slavery in practice. Source.

Key developments included:

Gradual emancipation laws passed in states such as Pennsylvania (1780) and Massachusetts (1783 court decisions).

Expanded free Black communities advocating for educational rights, property ownership, and civic participation.

Religious activism from Quakers and evangelical groups who argued that slavery was incompatible with Christian ethics.

A normal sentence here clarifies the broader consequences of these actions. While emancipation proceeded slowly, these reforms marked a major shift in public policy and moral expectations.

Persistence of Slavery in the South

In contrast, Southern leaders defended slavery as essential for economic stability and social order. Plantation agriculture—especially tobacco, rice, and indigo—depended on enslaved labor, and many white Southerners claimed that freedom for enslaved people would threaten prosperity and security. These regional differences laid groundwork for long-term sectional conflict.

Expanding Democratic Participation

Beyond slavery, revolutionary ideals inspired broader demands for greater political democracy. Many Americans sought reforms that expanded representation, reduced social hierarchies, and altered traditional patterns of authority.

Debates Over Voting Rights and Political Equality

Calls for expanded suffrage challenged longstanding property requirements. Although most states kept such requirements, debates intensified about whether political participation should be tied to economic status. These conversations reflected new beliefs that legitimate government must derive from the consent of the governed, not from inherited privilege.

Challenges to Aristocracy and Hierarchical Customs

Supporters of increased political equality pushed for:

Reducing deference to traditional elites.

Expanding access to public office.

Creating written constitutions with explicit protections for individual rights.

Encouraging civic education to cultivate republican virtue.

These efforts aimed to break down entrenched social hierarchies and encourage merit-based leadership rather than rule by wealthy families.

African American Activism and Community Building

Free and enslaved African Americans played an essential role in shaping debates about rights and democracy. Their petitions, speeches, and community institutions demonstrated deep engagement with revolutionary ideology.

Legal Petitions and Appeals to Natural Rights

Enslaved individuals in states such as Massachusetts and Connecticut argued in court that slavery contradicted the natural rights philosophy embedded in Revolutionary rhetoric. Their arguments directly linked Enlightenment principles to the quest for racial justice.

Growth of Free Black Communities

As emancipation proceeded in the North, free Black communities established new cultural, religious, and educational institutions.

Exterior view of Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church and Parsonage in Plymouth, Massachusetts, a historic congregation associated with the AME denomination. Churches like this one became centers of worship, education, and mutual aid for free Black communities, reflecting the growing institutional strength of Black religious life that had roots in the Revolutionary era. The building is from a later period than the AP focus, so it represents the longer-term legacy rather than an original Revolutionary-era structure. Source.

These developments included:

Independent Black churches encouraging mutual aid and activism.

Schools promoting literacy and civic involvement.

Voluntary societies addressing poverty, discrimination, and legal inequality.

A normal sentence here emphasizes that these communities became centers of leadership that shaped early African American political thought.

The Limits of Reform in the Revolutionary Era

Although revolutionary ideals sparked significant debate, structural change remained limited. Most Southern states reinforced slave codes, and racial discrimination persisted even where slavery ended. Property and gender restrictions continued to limit the scope of political democracy. Nonetheless, the era planted ideological seeds that would shape future struggles for abolition and equality.

Lasting Significance for the New Nation

The tension between republican ideals and enduring inequality became a central feature of early American life. Debates over slavery and democratic participation pushed Americans to confront contradictions in the nation’s founding principles, influencing political culture, social reform movements, and future conflicts over freedom and rights.

FAQ

Enslaved individuals sometimes brought “freedom suits” before local courts, arguing that slavery violated emerging constitutional principles or earlier legal precedents.

These cases often relied on:

References to natural rights and religious equality

Claims based on maternal descent, manumission promises, or technical errors in slaveholders’ documentation

Although not universally successful, these efforts showed how enslaved people actively used evolving legal frameworks to press for freedom.

Some prominent figures, particularly in the Upper South, expressed discomfort with slavery, acknowledging its contradiction with republican ideals.

However, their actions were constrained by:

Economic dependence on slave labour

Fear of social unrest

Political concerns about maintaining unity among the new states

This produced a gap between ideological critique and meaningful reform.

Antislavery sentiment circulated through sermons, pamphlets, and civic discussions that interpreted the Revolution’s promises of liberty as universal.

Community networks—especially religious congregations—played an important role:

Ministers preached against human bondage

Local societies debated moral consistency in public life

These environments helped ordinary colonists adopt antislavery positions even outside slaveholding regions.

Women, particularly in northern religious communities, supported antislavery causes through moral persuasion and community organising.

Their contributions included:

Petitioning local governments

Organising fund-raising or relief activities for free Black communities

Teaching literacy or religious instruction to formerly enslaved children

Although informal, their activism helped build the moral foundation of later abolitionist movements.

Free Black communities often modelled republican values by forming voluntary associations, churches, and mutual aid groups that emphasised civic responsibility.

Their activities helped:

Demonstrate the capacity of Black Americans for self-governance

Challenge racist assumptions in political debates

Encourage state-level conversations about equal protection and citizenship

These early institutions laid groundwork for long-term demands for civil rights and social equality.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Explain one way in which Revolutionary-era ideals contributed to early calls for the abolition of slavery.

Mark scheme:

1 mark for identifying a relevant Revolutionary ideal (e.g., natural rights, liberty, equality).

1 mark for explaining how this ideal created moral or political criticism of slavery.

1 mark for linking this criticism to early antislavery actions (e.g., petitions, gradual emancipation laws).

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Evaluate the extent to which debates over slavery during the Revolutionary era reflected broader struggles over political democracy in the new United States.

Mark scheme:

1–2 marks for describing debates over slavery, including challenges raised by enslaved people, reformers, or religious groups.

1–2 marks for explaining how these debates were connected to wider discussions about political equality, voting rights, or republican government.

1–2 marks for analysing the extent of change, including regional differences (e.g., Northern gradual emancipation vs. Southern entrenchment of slavery) and limits to reform.