AP Syllabus focus:

‘Many new state constitutions placed power in legislatures and kept property requirements for voting and citizenship, reflecting fears of strong executive authority.’

New state constitutions written after independence reflected Americans’ distrust of centralized authority, emphasizing legislative supremacy, restricted executive power, and property-based political participation to protect liberty and prevent potential tyranny.

State Constitutions in the Revolutionary Era

In the years immediately following independence, the former colonies rapidly drafted state constitutions—their foundational political documents—to replace British colonial charters. These constitutions reveal how Americans interpreted revolutionary ideals in practical governance. The guiding impulse was a desire to uphold republicanism, defined as a political system in which authority derives from the people rather than a monarch. To achieve this, most states sought to constrain executive authority and empower legislatures, believing that representative assemblies best expressed the people’s will.

First page of the Pennsylvania Constitution of 1776, illustrating how early states drafted written frameworks to replace colonial charters. The document reflects strong legislative authority and popular representation. Although it includes more text than required for the syllabus, it visually represents constitutional creation during the Revolutionary era. Source.

Republicanism: A form of government in which political power originates from the people, typically exercised through elected representatives rather than inherited rulers.

This emphasis on popular sovereignty strongly influenced the structural choices embedded within the new constitutions.

Legislative Supremacy and Distribution of Power

A dominant feature of early state constitutions was the elevation of legislative power. Many Americans associated tyranny with executive overreach—rooted in memories of royal governors who dissolved assemblies, vetoed colonial laws, and enforced unpopular British policies. As a result, state governments redistributed institutional power away from governors and toward elected legislatures.

Key Features of Legislative Supremacy

Unicameral or dominant bicameral legislatures: Some states, such as Pennsylvania, opted for a single-house legislature, while others preserved a two-house structure but still granted the legislature broad authority.

Control over appointments: Legislatures often appointed judges, executive officers, and even governors, ensuring that the executive branch remained subordinate.

Frequent elections: Short legislative terms ensured continual accountability to voters, reinforcing the belief that legislatures best reflected public sentiment.

Power over taxation and spending: Legislatures controlled fiscal policy, reflecting the revolutionary insistence that taxation must be tied to representation.

Many constitutions also sharply limited the governor’s role. Executive officers were often denied veto power, stripped of authority over the militia, or constrained by executive councils—bodies of advisory legislators who effectively prevented unilateral executive action.

Weakening of the Executive

This restrictive approach stemmed from fears that strong executives would replicate the arbitrary rule of colonial administration. Governors in many states lacked powers later associated with the U.S. presidency, such as independent appointment authority or the ability to direct foreign relations. Instead, constitutions positioned the executive as a cautious administrator, not an independent policymaker.

Voting, Citizenship, and Property Requirements

Despite expanding legislative power, the new constitutions did not embrace universal political participation. Instead, most preserved property requirements for suffrage and citizenship, reflecting deep concerns about social order and political stability.

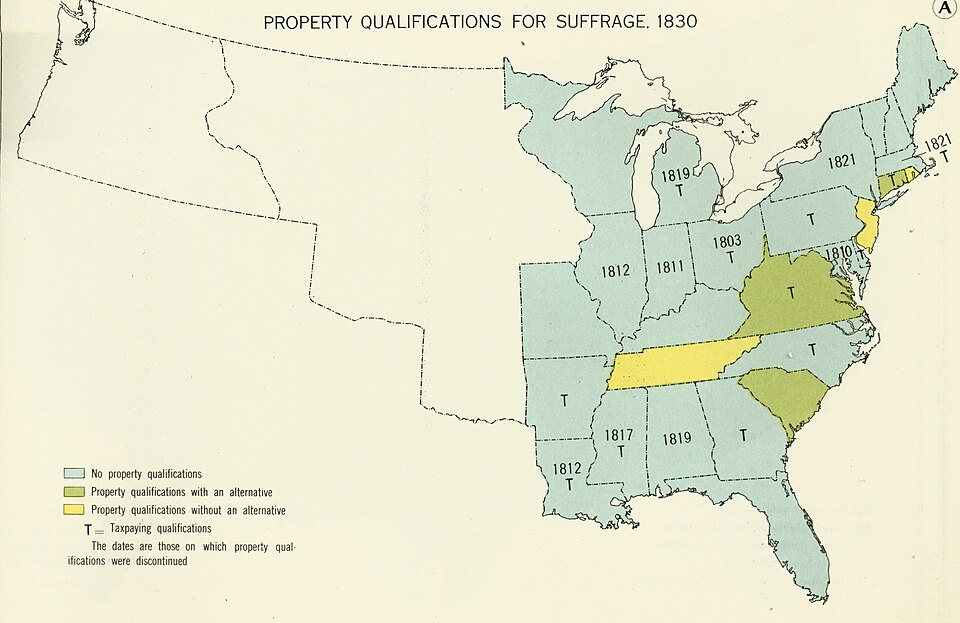

Map showing property-based suffrage restrictions in 1830, illustrating how voting rights were often tied to landownership or tax status. While slightly later than the Revolutionary period, it clearly visualizes the concept of property-linked political participation. The image includes extra later-era detail, but reinforces patterns established in early state constitutions. Source.

Suffrage: The right to vote in political elections, typically regulated by a state’s constitution or statutory laws.

These property-based qualifications reflected the belief that only individuals with economic independence possessed the judgment and virtue required for participatory republicanism. Property owners were presumed to be less susceptible to corruption, coercion, or factionalism.

Common Voting and Office-Holding Restrictions

Freehold property requirements: Many states required voters to own land of a specific value to demonstrate economic stake in society.

Taxpaying requirements: Some states permitted voting for certain offices only if the individual had paid local or state taxes.

Higher thresholds for officeholding: Candidates for state legislature or executive posts often needed to meet more stringent property qualifications than ordinary voters.

Citizenship requirements: States typically restricted political rights to free male citizens, excluding enslaved people, most free African Americans, women, and certain immigrant groups.

These restrictions reveal a persistent tension: while Americans embraced egalitarian rhetoric during the Revolution, many simultaneously defended hierarchical assumptions about who should wield political power.

State Declarations of Rights and Popular Sovereignty

Most constitutions included Declarations of Rights, articulating fundamental liberties such as freedom of speech, freedom of religion, jury trials, and protections against arbitrary arrest.

Manuscript page from the Massachusetts Constitution of 1780 showing its Declaration of Rights. This section codified essential liberties such as freedom of religion and due process, reflecting concerns that legislative dominance might threaten individual freedoms. The page contains more detail than required, but effectively illustrates how states formalized rights protections. Source.

Common Rights Guarantees

Protection against excessive bail or cruel punishment

Guarantees of due process and trial by jury

Freedom of the press

Prohibition of standing armies without legislative consent

Affirmation of natural rights and popular sovereignty

State Declarations of Rights also reinforced the notion that governments derived legitimacy from the consent of the governed. Even as legislatures gained power, constitutional framers sought to codify protections that limited governmental intrusion into personal liberty.

Broader Political Implications

The structure of early state constitutions influenced national political development. Their emphasis on legislative supremacy shaped debates at the Constitutional Convention, where many delegates criticized state governments for being too responsive to popular pressure, passing unstable laws, and weakening executive authority to the detriment of effective governance. These criticisms later informed calls for a stronger national constitution but also highlighted how early state constitutions represented a distinct phase in American political experimentation.

The early constitutions thus reveal a careful balancing act: harnessing revolutionary ideals, preventing executive tyranny, and maintaining a stable political community through property-based political participation and robust legislative authority.

FAQ

States justified their decisions based on their colonial experience and local political culture. Those with histories of conflict with royal governors, such as Virginia and Massachusetts, were more inclined to limit executive authority.

Some also drew on Enlightenment arguments that legislatures embodied the people’s will more directly, while executives posed inherent risks of concentrating power. As a result, justification often combined historical grievances with philosophical reasoning.

Unicameral systems appealed to states where radicals argued that a single house was the purest expression of democratic will and avoided elite domination.

However, many states retained bicameral structures to create an internal check within the legislature. Supporters believed that having two houses reduced the chance of rash lawmaking and balanced representation between different social or regional interests.

Although legislatures held extensive authority, states sought safeguards to prevent misuse of power.

Common measures included:

Annual or frequent elections

Mandatory public sessions to ensure transparency

Rotation in office to prevent long-term entrenchment

Prohibitions on legislators holding multiple offices simultaneously

These measures aimed to keep legislators accountable and limit the risk of factionalism.

Debates centred on how much property signified genuine independence. Some argued that minimal landownership was sufficient to demonstrate responsibility, while others believed stricter thresholds were necessary to preserve social stability.

These debates often reflected local economic conditions. In wealthier or more commercially diverse states, requirements varied sharply depending on whether land, personal property, or tax payment was used as the standard.

State constitutions often reshaped local administration by redefining the relationship between state legislatures and county or town authorities.

In some regions, legislatures gained greater control over local appointments, weakening traditional elites. In others, local governments retained broad autonomy in taxation, militia organisation, and court administration, reflecting long-standing practices of community self-rule.

Practice Questions

Explain one reason why many early state constitutions placed greater power in the legislature than in the executive. (1–3 marks)

Question 1: Explain one reason why many early state constitutions placed greater power in the legislature than in the executive. (1–3 marks)

1 mark: Identifies a relevant reason (e.g., fear of executive tyranny, distrust of strong governors).

2 marks: Provides a brief explanation showing how this reason influenced constitutional design.

3 marks: Offers a well-developed explanation linking historical experience under British rule to the emphasis on legislative supremacy.

Evaluate the extent to which property requirements for voting in early state constitutions reflected broader political beliefs in the post-Revolutionary era. (4–6 marks)

Question 2: Evaluate the extent to which property requirements for voting in early state constitutions reflected broader political beliefs in the post-Revolutionary era. (4–6 marks)

4 marks: Demonstrates general understanding of property requirements and mentions their connection to political beliefs about independence or virtue.

5 marks: Provides clear explanation of how property ownership was linked to political stability, republican values, or fears of disorder.

6 marks: Gives a well-supported evaluation addressing both how property requirements reflected wider republican ideology and any limitations or tensions this created, such as the exclusion of many groups from political participation.