AP Syllabus focus:

‘Social changes tied to the market revolution and greater social and geographic mobility contributed to the spread of the Second Great Awakening.’

The Market Revolution transformed everyday life, accelerating mobility, economic change, and social upheaval. These shifts created fertile conditions for widespread revivalism that defined the Second Great Awakening.

How Market Revolution Change Created Conditions for Revival

The early nineteenth-century Market Revolution—a broad transformation in transportation, communication, and economic organization—reshaped communities and daily experience in ways that encouraged many Americans to seek new spiritual foundations. This upheaval fostered anxiety, optimism, dislocation, and opportunity, all of which made revivalist religion appealing as a source of stability and meaning. As economic relationships expanded beyond local contexts, individuals experienced new uncertainties that encouraged participation in evangelical movements emphasizing personal salvation and moral self-discipline.

Expanding Transportation Networks and the Circulation of Ideas

New transportation systems radically extended Americans’ mobility.

“Map of the canals & rail roads of the United States, reduced from the large map of the U.S.; engraved by J. Knight,” 1840. This map highlights the expanding network of canals and railroads that connected eastern cities and interior regions, supporting greater geographic mobility and economic integration. The map also includes details such as canal cross-sections and an inset of southern Florida that extend beyond the syllabus but can be de-emphasized in favor of the main transportation patterns. Source.

Turnpikes, canals, and especially the steamboat dramatically reduced travel time and cost.

These routes enabled itinerant preachers to travel widely, linking the movement’s emotional preaching style to new geographic possibilities.

Mobile populations encountered unfamiliar communities, prompting many to search for grounding through religious participation.

This circulation of people also facilitated the spread of pamphlets, religious newspapers, hymnbooks, and printed sermons. Evangelical networks used these expanding routes to distribute materials that reinforced revival messages, helping standardize themes of repentance, redemption, and democratic religious access across vast regions.

New Mobility and Democratic Religious Participation

The Market Revolution also created unprecedented geographic mobility, encouraging millions to migrate westward into regions such as the Old Northwest and the Ohio River Valley. Many of these settlements lacked established institutions and social cohesion. Revivalism filled this institutional vacuum by offering shared rituals, community structure, and moral order. Camp meetings—large, multiday gatherings characterized by emotional preaching—thrived in these frontier environments, drawing settlers hungry for communal experience.

Camp meeting of the Methodists in North America, c. 1819. This engraving shows a large outdoor revival with a raised preaching platform, tents, and crowds typical of Second Great Awakening camp meetings. The image includes visual details such as clothing styles and forest scenery that go beyond the syllabus but help students imagine the social and physical setting of these revivals. Source.

The Democratic and Individualistic Appeal of Revivalism

Revivalism aligned naturally with the era’s democratic ethos. Preachers emphasized:

Individual choice, teaching that people could decide their own salvation.

Equality before God, resonating with broader societal values of political participation.

Accessible preaching, rejecting elite theological authority and empowering ordinary Americans.

This message attracted artisans, farmers, laborers, and migrants navigating the shifting social hierarchy produced by industrializing markets.

Economic Dislocation, Social Stress, and the Turn Toward Religion

The Market Revolution disrupted traditional labor rhythms, family relationships, and patterns of community life. Wage labor, urbanization, and the decline of household production introduced new forms of insecurity. Many Americans perceived these changes as both liberating and destabilizing.

Emerging Social Problems and Moral Concerns

Urbanization and factory growth generated visible societal challenges:

Rising poverty and inequality

Public drunkenness and crime concerns

Weakening of family and community oversight

Growth of transient labor populations

Revivalism addressed these anxieties by promoting moral self-regulation and communal accountability. Evangelical churches framed salvation as a path toward stability and moral improvement amid rapid change.

Moral Reform: A set of religiously inspired efforts to reshape personal behavior and social norms, often tied to temperance, sexual ethics, and family order.

Revivalist leaders believed that strengthening individual morality would restore social harmony disrupted by market-driven transformations. Their message appealed especially to women, who confronted shifting household roles and found in reform-oriented religious communities a source of authority and influence.

A wide range of Americans embraced this vision of spiritual regeneration, seeing religion as a way to impose moral structure on a rapidly changing world.

Communication Innovations and Religious Mobilization

Technological advances such as the telegraph facilitated the coordination of revival campaigns and reform organizations. Religious networks used these tools to synchronize events, share reports, and cultivate a sense of national religious momentum. Print culture flourished, enabling denominations such as the Methodists and Baptists to distribute literature on a national scale.

Institutional Expansion Supported by Market Forces

The Market Revolution not only changed individual lives but also strengthened the institutional capacity of evangelical denominations.

Churches developed publishing houses to produce tracts more efficiently.

Missionary societies organized national fundraising networks made possible by improved transportation.

Interconnected congregations across states shared strategies for preaching, recruitment, and conversion.

These developments transformed revivalism from scattered local movements into a coordinated national phenomenon.

Westward Expansion and the Spread of Frontier Revivalism

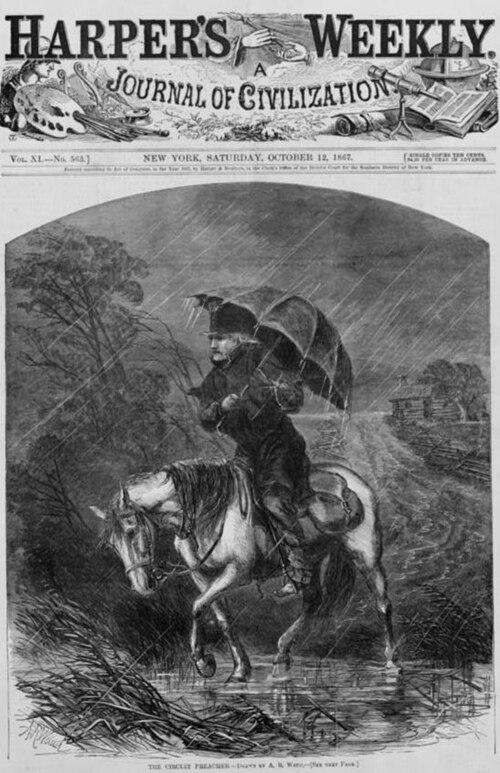

As Americans pushed into new territories, religious institutions followed. The mobile nature of frontier settlement fostered the success of circuit riders, ministers who traveled on horseback to preach across dispersed communities.

“The Circuit Preacher” by Alfred Waud, 1867. The image portrays a Methodist minister on horseback pressing through harsh weather to reach scattered congregations, reflecting the mobility that enabled evangelical religion to follow westward migration. The historical scene is slightly later than the core 1800–1848 AP period but accurately depicts the long-lasting circuit-rider pattern you reference. Source.

New Communities and the Role of Religion

Frontier households confronted material hardship, isolation, and limited institutional support. Evangelical revivalism provided:

Social networks

Mutual aid

A shared moral vocabulary

A sense of collective purpose

These functions made revivalism central to the cultural identity of new western regions.

Interplay of Mobility, Market Change, and Revival Growth

Together, the economic shifts and mobility of the Market Revolution did more than accelerate revivalism—they shaped its themes. Preachers stressed discipline, self-improvement, and personal responsibility, appealing to individuals navigating an economy that rewarded self-directed action. The fusion of economic transformation, geographic mobility, and democratic religious practice made the Second Great Awakening a defining feature of American social life between 1800 and 1848.

FAQ

Frontier settlements often consisted of young, mobile populations with few established institutions, making residents more open to new forms of religious community. Many settlers lacked traditional churches, clergy, or structured social networks, creating space for revivalists to step in as community builders.

Camp meetings offered collective experiences that addressed isolation, fostered social ties, and helped settlers negotiate rapid transitions in their lives.

Religious publishers expanded dramatically, producing affordable tracts, newspapers, and hymnbooks designed for mass circulation.

Key developments included:

Stereotype printing, which lowered production costs

National distribution networks operated by denominational societies

Standardised formats that allowed shared messages across regions

These print materials reinforced revivalist teachings in homes and workplaces, sustaining interest between preaching events.

Workers facing unpredictable employment, declining autonomy, and shifting workplace expectations sought emotional reassurance and moral direction.

Revivalist messages stressing self-discipline and personal salvation resonated with those adapting to market-driven routines.

Meetings also offered social recognition and leadership opportunities unavailable in hierarchical work settings.

Women frequently organised prayer circles, supported itinerant ministers, and maintained religious participation in transient communities.

Their domestic influence helped embed revivalist values within households, reinforcing moral expectations.

In areas with limited institutional structures, women served as essential connectors between migrating families, providing continuity as communities grew and dispersed.

Western territories lacked entrenched religious denominations, allowing revivalism to flourish without competition from established clergy.

Additional factors included:

High migration rates, which caused social fragmentation

Sparse populations that relied heavily on itinerant preachers

A cultural atmosphere that valued innovation over tradition

These conditions made frontier communities especially receptive to emotionally charged preaching and flexible religious organisation.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Explain one way in which increased geographic mobility during the Market Revolution contributed to the spread of the Second Great Awakening between 1800 and 1848.

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

1 mark: Identifies a valid link between geographic mobility and the spread of revivalism (e.g., itinerant preachers travelling more easily).

2 marks: Provides a clear explanation of how mobility supported revivalist activity (e.g., transportation networks enabled preachers to reach isolated communities).

3 marks: Offers a developed explanation showing a precise mechanism (e.g., the ability to travel via canals, roads, or steamboats allowed revivalist messages and printed materials to spread rapidly across growing frontier settlements).

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Evaluate the extent to which economic and social changes brought about by the Market Revolution created conditions that encouraged the growth of revivalism during the Second Great Awakening. In your answer, consider both economic forces and patterns of mobility.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

4 marks:

Identifies at least one economic change (e.g., new labour patterns, expanding markets) AND one social change (e.g., rising urbanisation or community disruption).

Makes a basic link between these changes and increased receptiveness to revivalism.

5 marks:

Provides developed analysis showing how Market Revolution changes created instability or opportunity that encouraged revivalist responses.

Uses specific examples (e.g., camp meetings on the frontier, growth of itinerant preaching, anxieties linked to wage labour or migration).

6 marks:

Offers a well-supported evaluation of the extent to which Market Revolution change fostered revivalism.

Demonstrates clear understanding of multiple factors, weighing their significance (e.g., mobility enabling circuit riders, economic uncertainty prompting moral reform, weakened community structures increasing demand for religious cohesion).

May acknowledge limitations or other contributing forces (e.g., ideological or theological developments independent of economic change).