AP Syllabus focus:

‘The U.S. expanded influence in the Western Hemisphere through diplomatic efforts such as the Monroe Doctrine and related foreign-policy assertions.’

The Monroe Doctrine marked a pivotal moment in early U.S. foreign policy, asserting hemispheric leadership as Americans sought security, independence, and influence during rapid political changes across the Americas.

Origins and Context of the Monroe Doctrine

The Monroe Doctrine emerged in 1823 during President James Monroe’s administration, shaped by shifting international conditions after the Napoleonic Wars. European powers—especially the Holy Alliance of Austria, Prussia, and Russia—signaled interest in restoring monarchies in newly independent Latin American countries. The United States viewed these developments as threats to its security and its vision for a hemisphere free from European interference. At the same time, Britain, seeking to protect its trade networks, encouraged the United States to oppose renewed European colonial ambitions.

Key Motivations Behind U.S. Policy

U.S. policymakers used the Doctrine to articulate a broader strategic position in the Western Hemisphere. Several factors motivated its creation:

Security concerns, particularly fears that European intervention could destabilize North American borders.

Commercial ambitions, as expanding trade with Latin American republics aligned with American economic goals.

National self-definition, with policymakers eager to frame the United States as a defender of republican ideals.

Growing diplomatic confidence, spurred by recent successes such as the Transcontinental Treaty (Adams-Onís Treaty), which secured Florida and defined U.S. boundaries.

The Core Principles of the Monroe Doctrine

Secretary of State John Quincy Adams, the primary architect of the policy, ensured that the Doctrine would assert a bold, unified statement of national purpose. President Monroe delivered these principles in his annual message to Congress on December 2, 1823.

Non-Colonization

The Doctrine declared that the Western Hemisphere was “no longer open to colonization.” This principle warned European powers not to establish new settlements or expand territorial control in the Americas.

Map of the Western Hemisphere, showing North and South America together as a single geographic region. This is the area the United States claimed as a special sphere of interest in the Monroe Doctrine. The map does not show political borders for 1823, but it clearly outlines the hemisphere to which the doctrine applied. Source.

Non-Colonization Principle: A declaration that European nations were prohibited from acquiring new territories in the Western Hemisphere.

This statement reinforced U.S. ambitions to shape political developments in North America without direct competition from traditional imperial rivals.

Non-Intervention

A second pillar insisted that European powers must not interfere in the political affairs of the newly independent Latin American nations. This claim symbolized a broader U.S. commitment to protect republican governments from monarchical restoration.

Non-Intervention Principle: A foreign-policy assertion that external powers should not interfere in the domestic or international affairs of American nations.

This concept aligned with the United States’ emerging identity as a distinct political and ideological force in global affairs.

Asserting Influence in the Western Hemisphere

Although the Monroe Doctrine rested on diplomatic language rather than military capability, it quickly became a central expression of American hemispheric influence. Policymakers used the Doctrine to set a long-term foreign-policy foundation.

Linking Diplomacy to National Interests

The Doctrine had several immediate diplomatic effects:

It reassured new Latin American nations that the United States would oppose European reconquest.

It aligned U.S. diplomacy with British interests without forming a formal alliance.

It signaled that the United States aimed to shape international norms in the hemisphere.

Establishing U.S. Foreign-Policy Identity

The Monroe Doctrine contributed to a clearer American identity in global affairs. Asserting independence from both European alliances and European rivalries, it framed the republic as a steward of Western Hemisphere autonomy. It reflected American nationalism, an expanding sense of mission, and a belief that the United States held a special role in defending republicanism.

Long-Term Significance and Interpretations

Though initially limited in power, the Doctrine gained increasing significance over time. Later generations of U.S. leaders invoked it to justify more assertive forms of influence, making the Doctrine a flexible, expanding tool of U.S. foreign policy.

“In December 1823, President James Monroe’s annual message to Congress announced the Monroe Doctrine, drafted largely by Secretary of State John Quincy Adams.”

Official portrait of President James Monroe, painted by Samuel F. B. Morse around 1819, during Monroe’s presidency. Monroe’s administration issued the Monroe Doctrine, asserting that the Americas were no longer open to new European colonization. This image helps situate the doctrine in the broader political leadership of the early 1820s. Source.

Immediate Limitations

Despite its bold claims, the United States in the 1820s lacked a navy or army strong enough to enforce the Doctrine. Britain’s powerful Royal Navy largely ensured that European powers did not challenge the policy. Nonetheless, the Doctrine’s symbolic value was immense.

Enduring Foreign-Policy Framework

Over the nineteenth century, leaders reinterpreted the Doctrine to support broader ambitions. Its original purpose—warning against European encroachment—shifted to encompass:

Protection of American commercial interests in the Caribbean and Central America

Rhetorical justification for territorial expansion

Reinforcement of U.S. political authority in neighboring regions

Diplomatic Influence and American Identity

The Doctrine played a critical role in shaping American diplomatic identity. It positioned the United States as a guardian of hemispheric autonomy, offered a framework for responding to international crises, and demonstrated the increasingly global reach of American political ideas.

“Later leaders invoked the Monroe Doctrine as a justification for more assertive U.S. involvement in Latin America, turning a defensive warning into a broader claim of regional leadership.”

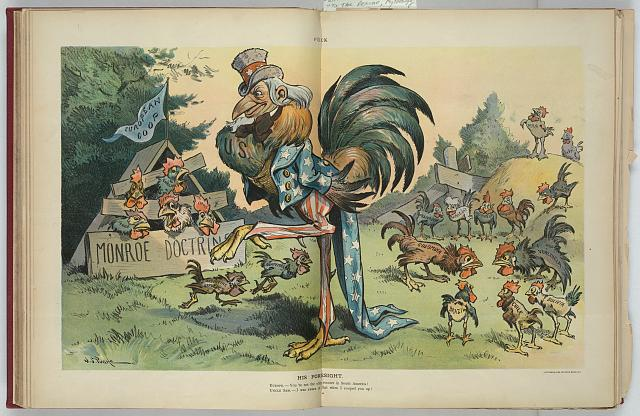

Political cartoon titled “His foresight,” showing Uncle Sam as a large rooster guarding free-roaming Latin American chicks while European powers are confined in a coop labeled “Monroe Doctrine.” The image reflects a later interpretation of the doctrine as protecting the Western Hemisphere from European interference and affirming U.S. leadership in the region. It includes extra detail—specific Latin American country names and early-1900s European rivals—that goes beyond Period 4 but illustrates the doctrine’s long-term influence. Source.

The Monroe Doctrine as a Hemispheric Assertion

By grounding foreign policy in principles of non-colonization, non-intervention, and hemispheric autonomy, the Monroe Doctrine expressed a new American leadership vision. It embodied early-republic ambitions to secure borders, encourage commerce, advance republican ideals, and cultivate long-term diplomatic authority throughout the Western Hemisphere.

FAQ

Adams argued strongly that the United States should issue its own independent statement rather than join a joint declaration with Britain. He believed aligning with Britain would undermine American authority and limit future diplomatic flexibility.

He persuaded Monroe to frame the Doctrine not merely as a response to Europe, but as a long-term principle defining the Western Hemisphere as a distinct political sphere.

Adams’s influence ensured the Doctrine had a confident, forward-looking tone rather than a defensive one.

Many new republics viewed the Doctrine as a useful diplomatic shield because it discouraged European powers from attempting reconquest. Although the United States could not enforce the Doctrine alone, Britain’s naval dominance made European intervention less likely.

Latin American leaders often interpreted the Doctrine as moral support for republican government, even if they remained cautious about potential US ambitions.

European governments largely dismissed the Doctrine as an American political statement with no legal standing, given the United States’ modest naval capability.

However, most powers avoided directly challenging it because Britain’s strategic interests aligned with keeping other European states out of Latin America.

The lack of open resistance allowed the Doctrine to gain credibility even without a formal enforcement mechanism.

Yes. Before the 1820s, American leaders were cautious about endorsing independence revolutions abroad. The Doctrine signalled a shift toward seeing Latin American independence as beneficial for US security and commerce.

It also encouraged the development of informal diplomatic relationships, trade links, and occasional recognition of new governments, strengthening regional ties.

The Doctrine reinforced the idea that the United States had a unique republican mission distinct from European monarchical traditions. This supported a growing belief that the nation was responsible for safeguarding political independence throughout the hemisphere.

It also contributed to domestic political pride by framing the country as a guardian of liberty, even though practical enforcement still relied heavily on British power.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Explain one reason why the United States issued the Monroe Doctrine in 1823.

Mark scheme

1 mark for identifying a relevant reason (e.g., to prevent European recolonisation of Latin America).

1 mark for showing contextual awareness (e.g., referencing newly independent Latin American states or post-Napoleonic European ambitions).

1 mark for linking the reason to a broader US aim (e.g., securing American political and economic interests in the Western Hemisphere).

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Analyse how the Monroe Doctrine asserted the growing influence of the United States in the Western Hemisphere between 1823 and the mid-19th century.

Mark scheme

1–2 marks for describing key components of the Monroe Doctrine (e.g., non-colonisation, non-intervention).

1–2 marks for explaining how these principles limited European involvement in the Americas.

1–2 marks for showing how the Doctrine reflected or advanced US diplomatic confidence, hemispheric leadership, or national identity.