AP Syllabus focus:

‘Even as democracy expanded for White men, many Americans remained excluded from voting by race, gender, age, and other legal restrictions.’

Groups Excluded from Expanding Suffrage

Although many states removed property requirements for White men, suffrage restrictions continued to shape political participation. These restrictions reflected longstanding assumptions about citizenship, political capacity, and social hierarchy in the early republic. Laws varied by state, but together they created a system in which voting rights were unevenly distributed and deeply influenced by race, gender, and economic concerns.

Racial Exclusion and the Structure of Citizenship

Despite some early-state constitutional provisions allowing limited African American suffrage, most states either barred Black men from voting outright or imposed barriers that made participation unrealistic. By the 1830s, as universal White manhood suffrage spread, many states explicitly restricted voting to White males, narrowing earlier voting rules and codifying racial exclusion.

Free Black men were disenfranchised in many northern states after 1800, even where they paid taxes.

Southern states strictly prohibited Black voting, reinforcing slavery’s racial hierarchy.

Racial exclusions were justified by arguments that political rights required racial “fitness” or alignment with dominant cultural norms.

These policies not only denied African Americans political voice but also reinforced broader systems of racial discrimination in everyday life.

Disenfranchisement: The legal or administrative removal of an individual or group’s right to vote.

Disenfranchisement shaped political culture by limiting the diversity of voices influencing debates over policy, governance, and national identity.

Gender Restrictions and the Ideology of Political Capacity

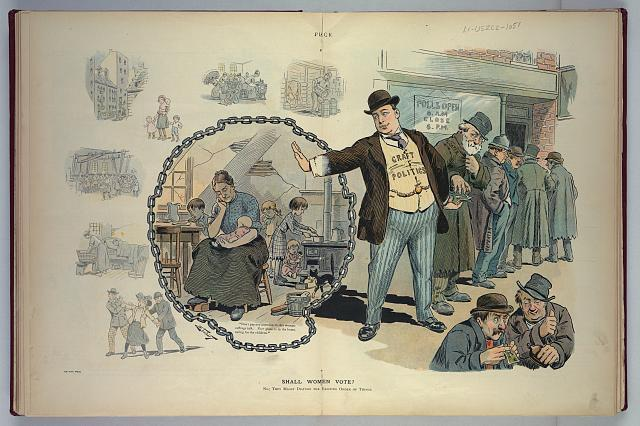

Women—regardless of wealth, education, or marital status—were broadly excluded from voting during this era.

This cartoon depicts a man preventing a woman from speaking while distributing money to male voters, illustrating how women were excluded from formal politics despite widespread electoral participation by men. It highlights cultural beliefs that politics belonged to men and portrays the exploitation underpinning early suffrage systems. The cartoon includes later industrial-era details not covered in this syllabus, but visually demonstrates long-standing gender exclusion. Source.

Most states justified women’s exclusion by defining politics as part of the public sphere, which was believed to be unsuitable for women’s perceived domestic roles.

Legal and Cultural Limits on Women’s Political Participation

Women’s disenfranchisement was rooted in both law and custom:

Voting laws used male-specific language such as “freemen” or “male citizens.”

Married women lacked independent legal identity under coverture, limiting their capacity to claim civil or political rights.

Cultural norms argued that women’s moral influence should operate within the home, not through electoral politics.

Coverture: A legal doctrine under which a married woman’s legal and economic identity was subsumed by her husband.

Even women active in reform movements, including abolition and temperance, remained excluded from formal political participation despite contributing to national debates.

Indigenous Peoples and the Limits of Political Belonging

Indigenous nations were treated as separate political communities, not as constituents of U.S. democracy. Their sovereignty placed them outside the political framework of American elections, while federal Indian policies further marginalised them.

Native American Exclusion

Indigenous peoples faced multiple forms of exclusion:

Most states did not consider Indigenous individuals living in tribal communities as citizens eligible to vote.

Federal policy—particularly removal efforts—prioritised territorial expansion over recognising Indigenous political rights.

Attempts by some individuals to vote were rejected on the grounds that tribal membership conflicted with U.S. citizenship requirements.

These exclusions reinforced the idea that political participation was tied to cultural assimilation and territorial control.

Age, Class, and Other Legal Restrictions

Although property qualifications declined for White men, other barriers persisted. States commonly set minimum age requirements for voting, and some maintained tax-paying requirements or residency rules to regulate access to elections.

Legal Barriers Beyond Race and Gender

Key restrictions included:

Age requirements, typically set at 21, limiting youth participation.

Residency requirements, which prevented recently migrated labourers or western settlers from voting until they met state-specific timelines.

Tax requirements in select states, which linked suffrage to fiscal contribution.

These restrictions reflected lingering beliefs that stable, settled, and economically responsible individuals were best suited for political participation.

Citizenship, Immigration, and Voting Restrictions

The early nineteenth century saw significant immigration, particularly from Ireland and Germany. While many immigrants eventually gained voting rights, the process was shaped by evolving definitions of citizenship and fears about foreign political influence.

Obstacles for Immigrant Voters

Immigrants encountered several barriers:

Naturalisation requirements mandated years of residency before citizenship—and voting rights—were granted.

Some states and political groups argued that immigrants lacked sufficient familiarity with American political traditions.

Anti-immigrant sentiment grew in some regions, foreshadowing later nativist political movements.

These barriers showed how the concept of political belonging remained contested even as the electorate broadened.

Expanding Democracy and Its Contradictions

The era’s democratic expansion rested on assumptions about who should be included in the political community. While universal White manhood suffrage broadened the electorate, it simultaneously sharpened exclusions for groups outside this category. The rise of mass politics thus existed alongside persistent inequalities, demonstrating that the United States’ movement toward democracy was uneven and deeply shaped by social hierarchies.

Political Culture and Exclusion

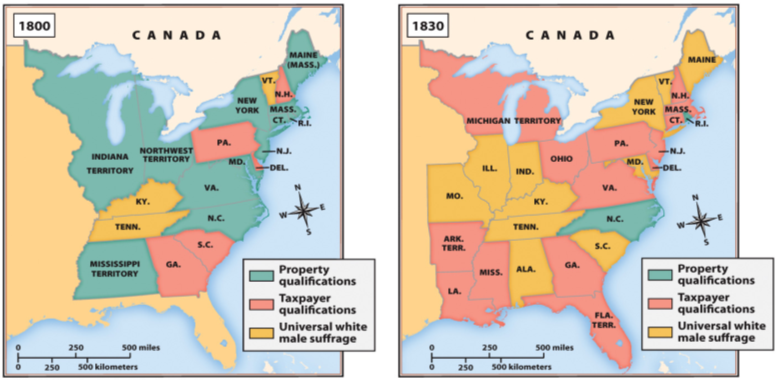

White men without property in many states gained the right to vote, but African Americans, women, Native peoples, and most noncitizen immigrants remained outside the electorate.

These maps compare voting qualifications in 1800 and 1830, illustrating the shift from property-based suffrage to universal white male suffrage. Although labelled “universal,” the electorate excluded women and people of colour, reinforcing racially and gender-limited democracy. The maps include additional territorial labels beyond the syllabus period, but effectively demonstrate the narrowing of political inclusion. Source.

The groups excluded from voting nonetheless influenced political life through informal means:

African American activists built community organisations and petitioned for rights despite disenfranchisement.

Women shaped public discourse through reform movements and voluntary associations.

Indigenous nations negotiated treaties and asserted sovereignty in the face of federal expansion.

These efforts highlighted that political exclusion did not eliminate political agency, but it did constrain access to formal power and electoral influence.

FAQ

Northern states often expanded suffrage to appeal to poorer White voters, who increasingly viewed political rights as a marker of racial status.

Lawmakers used racial exclusion to strengthen cultural notions of whiteness and maintain social cohesion among White citizens during a period of rapid economic and demographic change.

In some cases, fears of growing free Black communities contributed to efforts to restrict their political influence despite earlier, more inclusive laws.

Election days were often held in male-dominated public spaces such as taverns or courthouses, which could be unwelcoming or unsafe for marginalised groups.

Polling places were sometimes controlled by local elites or party operatives, who had discretion to challenge a person’s eligibility.

These informal practices reinforced legal exclusions by creating social barriers that discouraged or prevented participation.

Many Americans claimed that tribal allegiance was incompatible with U.S. citizenship and that Indigenous communities were “separate nations” outside the political system.

Officials also argued that Indigenous peoples were insufficiently assimilated, using cultural differences as justification for denying political rights.

This approach aligned with federal policies that prioritised territorial expansion over recognising Indigenous sovereignty or citizenship.

Frequent movement meant many labourers and settlers failed to meet strict state residency timelines, even if they contributed economically to their communities.

States used residency rules to ensure “stable” populations were voting, reflecting assumptions that transient workers were less informed or less invested in local issues.

As a result, mobile populations—especially young, poor, or western individuals—remained politically marginal despite the era’s egalitarian rhetoric.

Some political leaders believed recent immigrants lacked familiarity with American institutions and might be swayed by foreign loyalties or radical ideas.

Parties sometimes campaigned on limiting immigrant political power, especially in cities experiencing rapid demographic change.

These concerns encouraged stricter naturalisation timelines and helped embed the idea that full political membership required cultural as well as legal assimilation.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Identify and explain one reason why many Americans remained excluded from voting during the early nineteenth century despite the expansion of suffrage for White men.

Mark scheme:

1 mark for identifying a valid reason for exclusion (e.g., racial laws, gender norms, citizenship restrictions).

1 mark for explaining how this reason operated in practice (e.g., explicit constitutional language, cultural beliefs about political “fitness”).

1 mark for linking the exclusion to broader ideas about political capacity or social hierarchy.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Analyse how differing forms of legal and cultural restriction shaped patterns of political exclusion in the period 1800–1848.

Mark scheme:

1 mark for identifying at least two distinct forms of restriction (e.g., race, gender, age, residency).

1 mark for explaining how legal barriers limited access to the electorate.

1 mark for explaining how cultural norms reinforced or justified these legal limits.

1 mark for discussing how these restrictions produced an electorate defined primarily by White manhood.

Up to 2 additional marks for a cohesive, well-developed analysis that clearly connects restrictions to broader democratic contradictions in the era.