AP Syllabus focus:

‘Frontier settlers often championed expansion, while American Indian resistance prompted wars and federal efforts to control and relocate Indigenous peoples.’

Westward movement during the early nineteenth century intensified conflicts between frontier settlers, American Indian nations, and the federal government, generating competing visions of land use, sovereignty, and national growth.

Frontier Expansion and Ideologies of Growth

Growing numbers of White Americans migrated into regions beyond the Appalachians, encouraged by cheap land, expanding markets, and shifting political priorities. This movement was driven in part by expansionist ideology, especially the belief that republican settlement would strengthen the nation.

Economic and Social Motivations

Frontier migrants often sought opportunity in agriculture and trade. Many families expected western territories to provide long-term prosperity, believing that access to land fostered independence and civic virtue. Their expectations created political pressure on federal leaders to open more regions for U.S. occupation.

Federal Land Policies

The federal government promoted westward migration through surveying, land ordinances, and military outposts.

New states admitted during this period expanded political representation for frontier settlers.

Frontier voters frequently supported politicians who promised to defend and enlarge White settlement zones.

Indigenous Resistance to Encroachment

As settlers entered lands long inhabited by American Indian nations, conflict intensified. Many Indigenous communities rejected the loss of sovereignty and territory, resisting both diplomatically and militarily.

Varieties of Indigenous Resistance

Diplomatic strategies included petitions, negotiations, and the formation of intertribal alliances aimed at restraining U.S. expansion.

Military resistance involved defending homelands against settler militias and federal troops.

Legal resistance emerged as nations such as the Cherokee pursued recognition of treaty rights through the federal court system.

Sovereignty: The authority of a nation or people to govern itself without external control.

Resistance movements often aimed to preserve cultural life as well as territorial integrity, highlighting the deep ties between Indigenous identity and specific homelands.

Major Conflicts During the Period

In the Old Northwest, leaders such as Tecumseh worked to unify tribes against U.S. land claims, culminating in conflicts like the Battle of Tippecanoe (1811).

Map showing the approximate borders of Tecumseh’s Confederacy around 1810 in the Old Northwest. It illustrates the unified resistance movement formed by multiple Native nations against U.S. expansion. The map also includes surrounding regions and water bodies that go beyond the syllabus but provide helpful geographic context. Source.

In the Southeast, tensions escalated among the Creek, Seminole, and Cherokee nations, each responding differently to settler pressure and federal directives.

Military expeditions, frequently justified as defensive operations, resulted in the destruction of villages and food supplies, weakening Native resistance.

Federal Relocation Policy

By the 1820s and 1830s, federal policymakers increasingly embraced removal as the primary solution to frontier conflict. During Andrew Jackson’s presidency, these efforts hardened into a comprehensive relocation program.

Indian Removal Act of 1830

This law authorized the president to negotiate treaties exchanging Indigenous homelands in the East for lands west of the Mississippi River. Although framed as voluntary exchange, the legislation was implemented through intense coercion.

Treaty: A formal agreement between sovereign entities that establishes rights, obligations, or land transfers.

Despite treaty language claiming mutual consent, many agreements were signed under pressure or by minority factions within nations, raising disputes over legitimacy.

Implementation and Federal Power

Federal authorities worked with state governments to pressure Native communities into leaving:

States extended their laws over Indigenous nations, undermining independent governance.

Federal agents supervised treaty councils and regulated the movement of Native peoples.

U.S. troops enforced removal orders when communities resisted.

Indigenous Legal Resistance

Several nations attempted to halt removal through U.S. courts:

The Cherokee Nation argued for recognition as a distinct political community.

In Worcester v. Georgia (1832), the Supreme Court affirmed federal protection of Cherokee sovereignty, asserting that state laws had no jurisdiction within Nation lands.

Jacksonian officials, however, refused to enforce the ruling, illustrating how executive power shaped the relocation process.

The Experience of Removal

The most notorious removal event, the Trail of Tears, involved the forced migration of approximately 16,000 Cherokee people between 1838 and 1839.

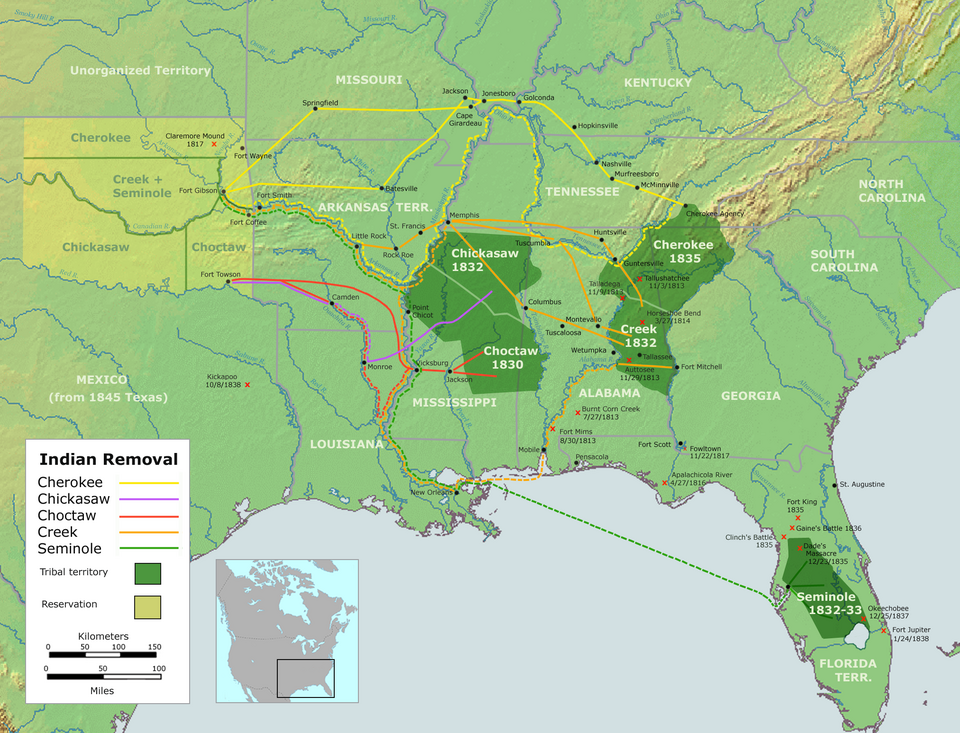

Color map showing major routes of the Trails of Tears from the Southeast to Indian Territory between 1836 and 1839. It highlights the Cherokee route while also indicating paths taken by other removed groups, illustrating the scale of forced migration. Extra geographic labels extend beyond syllabus requirements but help situate these movements within a wider landscape. Source.

Broader Consequences

Many southeastern nations—including the Creek, Chickasaw, Choctaw, and Seminole—underwent similar removals, though the Seminole resisted for years in a protracted conflict in Florida.

The creation of Indian Territory in present-day Oklahoma reorganized the demographic and political landscape of the West.

Displacement fractured community structures and disrupted traditional economies, yet many nations rebuilt political institutions in their new homelands.

Frontier Expansion and Federal Authority

The relocation policy represented both an assertion of federal authority and a concession to frontier demands. Expansionists celebrated the opening of new farmland, while opponents criticized the humanitarian and constitutional implications.

Political Implications

Jacksonian Democrats framed removal as promoting national security and frontier stability.

Critics, including some Whigs and religious reformers, condemned removal as incompatible with republican morality.

The conflict over removal exposed tensions between states’ rights, federal supremacy, and Indigenous sovereignty.

Long-Term Impact

By 1848, removal had reshaped the geographic boundaries of the United States and defined federal approaches to territorial management. The policy reinforced racial hierarchies and facilitated further western settlement, while Indigenous resistance continued in new forms across the expanding republic.

FAQ

Many settlers believed expansion fulfilled a civic and moral duty, arguing that republican society required widespread landownership. This belief framed westward movement as essential to preserving liberty.

They also saw Indigenous land use as incompatible with their own agricultural model, claiming that transforming the landscape into farms demonstrated progress. Such assumptions helped normalise policies that displaced Native communities.

Indigenous leaders used diplomacy to build regional alliances, share intelligence, and coordinate responses to U.S. pressure. These networks allowed nations to negotiate collectively and resist divide-and-rule tactics.

Some alliances pursued parallel diplomatic channels with the United States, using treaty negotiations to delay land loss or secure promises of protection. These strategies highlight the political sophistication of Indigenous diplomacy during the period.

Different communities faced varying economic pressures, political divisions, and assessments of U.S. power. Some leaders believed limited accommodation could preserve autonomy or prevent violence.

Accommodation often reflected:

Internal debates over survival strategies

Exhaustion after repeated conflicts

Desire to avoid military destruction seen in neighbouring nations

These choices reveal the complexity of Indigenous responses rather than simple acceptance of U.S. expansion.

States in the Southeast pushed aggressively for access to Indigenous lands, especially after agricultural potential and resource discoveries raised local demand.

Georgia, in particular, acted by extending state law over Cherokee territory, undermining tribal governance and pressuring federal leaders to support removal. This state-level activism accelerated federal policy commitments and shaped the implementation of removal.

Removal required significant administrative coordination, including organising transport, securing rations, and supervising routes to Indian Territory.

Challenges included:

Inadequate supplies and poor-quality food

Seasonal hazards such as extreme heat or winter exposure

Disease outbreaks in crowded encampments

Delays caused by disputes over treaty legitimacy

These logistical failures contributed heavily to the suffering and mortality experienced during forced migrations.

Practice Questions

(1–3 marks)

Identify one reason why many Indigenous nations resisted frontier expansion in the early nineteenth century.

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Award up to 3 marks.

1 mark for a basic identification of a reason (e.g., loss of land).

2 marks for identifying and providing brief contextual explanation (e.g., defending homelands central to cultural identity).

3 marks for a fully developed reason with clear reference to the period (e.g., Indigenous nations resisted because U.S. settlement threatened their sovereignty, territorial integrity, and long-standing cultural ties to specific regions).

(4–6 marks)

Explain how federal relocation policy in the 1830s affected both Indigenous sovereignty and the expansionist aims of the United States. In your answer, use specific evidence from the period 1800–1848.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Award up to 6 marks.

1–2 marks for a general description of relocation policy (e.g., Indian Removal Act authorised exchange of eastern lands for western territory).

3–4 marks for explaining impact on Indigenous sovereignty (e.g., undermined self-government, disregard of Supreme Court rulings such as Worcester v. Georgia, coercive treaties).

5–6 marks for analysing how removal advanced U.S. expansionist aims with specific evidence (e.g., clearing land for White settlement, political support from frontier voters, establishment of Indian Territory) and making clear links between policy implementation and broader territorial growth.