AP Syllabus focus:

‘Union victory and contested Reconstruction ended slavery and secession but left unresolved questions about federal power and citizenship rights.’

The Civil War and Reconstruction reshaped federal authority and citizenship, expanding national power while exposing deep conflicts over rights, equality, and the role of government in defining belonging.

Comparing How the War Changed Federal Power and Citizenship

Expanding Federal Authority Through War

The Civil War required an unprecedented mobilization of national resources, prompting the federal government to assert powers not previously exercised. Both wartime necessity and political ideology contributed to this expansion. By comparing prewar and wartime authority, students can trace how the crisis pushed the federal government beyond its earlier, more limited role.

Conscription, taxation, and the issuance of greenbacks demonstrated federal intervention in the economy and society.

National control over military strategy and supply chains eclipsed previous reliance on state-led militia systems.

The suspension of habeas corpus, a constitutional protection requiring lawful grounds for detention, exposed wartime tensions between civil liberties and security.

Habeas corpus: A legal protection requiring that individuals cannot be held without being brought before a court to determine the lawfulness of their detention.

These wartime policies revealed a shifting balance of power, with the federal government emerging as the decisive authority in matters of national survival.

Defining Citizenship Before and After the War

Before the Civil War, American citizenship lacked a consistent national definition. Rights varied by state, and enslaved people were legally excluded. The war and its aftermath forced the nation to articulate who counted as a citizen and what rights citizenship guaranteed.

The destruction of slavery demanded new legal categories for the formerly enslaved.

State-based definitions were replaced by federal standards, fundamentally altering governance structures.

Citizenship debates extended beyond African Americans to include women, American Indians, and immigrants, highlighting contested national identity.

Citizenship: The legal and political status that confers rights, protections, and obligations within a nation, determining who belongs and on what terms.

The comparative perspective emphasizes that citizenship was no longer solely a state-defined concept but increasingly a federal concern shaped by constitutional change.

The Reconstruction Amendments and Shifts in Federal Power

The 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments marked a profound transformation in federal authority. Each amendment established national standards of rights that states could not violate, redefining the relationship between individuals, states, and the federal government.

The 13th Amendment abolished slavery nationwide, replacing state-by-state variation with national uniformity.

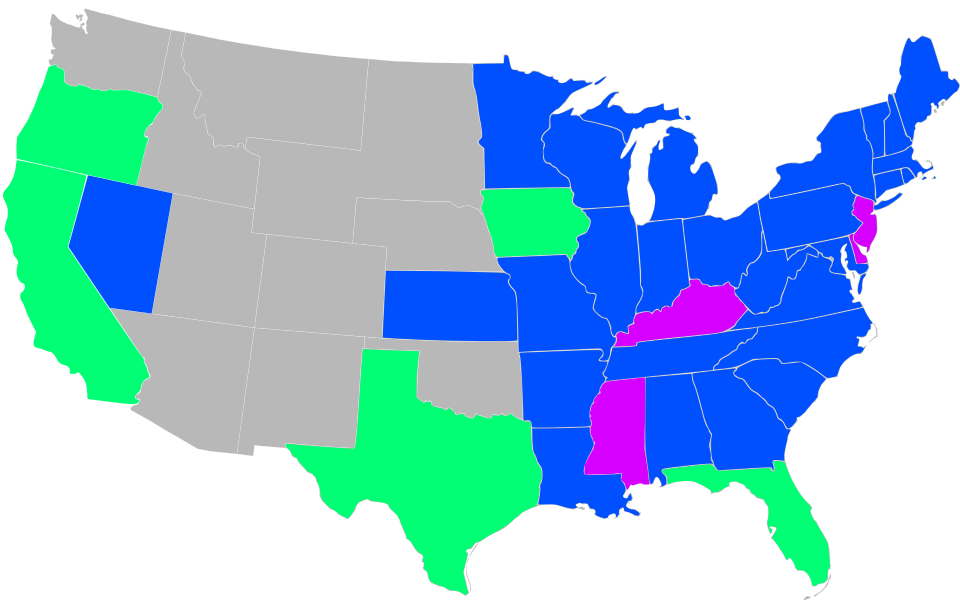

Map showing the order in which states ratified the 13th Amendment ending slavery. Colors indicate ratification timing, while gray regions depict territories not yet states. Some later ratifications extend beyond the syllabus period but illustrate long-term nationalization of freedom. Source.

The 14th Amendment established birthright citizenship and required equal protection of the laws, giving federal courts new oversight powers.

The 15th Amendment prohibited racial discrimination in voting, authorizing federal enforcement of electoral rights.

Federal Enforcement and Its Limits

Although Reconstruction expanded federal enforcement powers, their effectiveness depended on political will. Military occupation in the South, the Freedmen’s Bureau, and civil rights legislation demonstrated federal attempts to create a biracial democracy.

Enforcement Acts sought to suppress the Ku Klux Klan and protect Black voting rights.

Bureau agents facilitated labor contracts, education, and relief, acting as federal representatives in local communities.

Federal courts gained new roles in adjudicating civil rights violations, but inconsistent rulings limited impact.

Resistance was persistent. White supremacist violence, state-level obstruction, and Supreme Court decisions such as Slaughterhouse and U.S. v. Cruikshank narrowed the scope of federal power. This comparison underscores how federal authority expanded in theory but remained contested in execution.

Citizenship Rights in a Contested Reconstruction

Though Reconstruction redefined national citizenship, many rights remained fragile. Comparing wartime aspirations to postwar outcomes reveals deep tensions shaping the nation’s legal order.

Black Americans gained legal freedom and political rights but faced widespread violence and economic dependency.

Women’s rights advocates challenged their exclusion from the new constitutional order, leading to divisions within reform movements.

American Indians continued to face federal policies aimed at control rather than inclusion, showing the uneven application of citizenship principles.

These contrasts highlight that citizenship in the Reconstruction era underwent both expansion and retrenchment.

Long-Term Consequences for Federal Power and Citizenship

While Reconstruction ultimately collapsed due to waning Northern resolve and Southern resistance, its constitutional changes remained. Over time, the 14th Amendment in particular became the foundation for future civil rights decisions, illustrating a long-term shift toward federal protection of individual rights.

Federal authority over civil rights expanded gradually across the twentieth century.

Citizenship rights became anchored in national, not state, definitions.

Reconstruction’s contested legacy continued to shape debates about equality, liberty, and federal responsibility.

The Civil War and Reconstruction thus transformed federal power and the meaning of citizenship, setting enduring precedents that would influence American political development for generations.

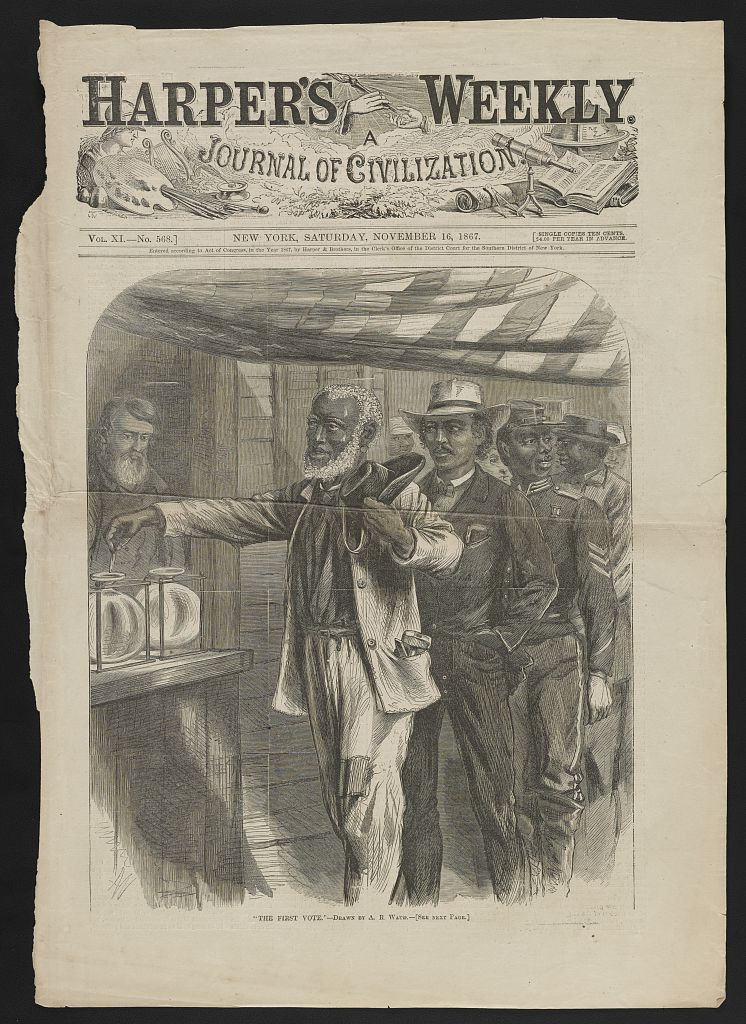

Engraving from Harper’s Weekly depicting African American men of varied backgrounds casting ballots in 1867. Their participation illustrates how Reconstruction and the 15th Amendment opened formal political citizenship to Black men under federal protection. The image does not show the later suppression of voting but captures a pivotal moment of expanded rights. Source.

FAQ

Decisions such as the Slaughterhouse Cases (1873) and United States v. Cruikshank (1876) significantly narrowed federal authority by interpreting the Reconstruction Amendments in ways that limited national protection of individual rights.

These rulings distinguished between state and federal citizenship and restricted the federal government’s ability to intervene when states failed to safeguard civil rights, contributing to an uneven national application of citizenship protections.

Federal enforcement depended heavily on political will, funding, and cooperation from local officials—conditions often absent in the postwar South.

Violent resistance from white supremacist groups, combined with obstructive state governments and inconsistent federal oversight, meant that rights granted on paper were not always realised in practice.

The Bureau served as a federal presence in daily life, demonstrating an expanded national responsibility for protecting rights.

It influenced emerging definitions of citizenship by:

• mediating labour contracts

• establishing schools

• offering legal assistance

These activities helped assert that citizenship involved federal guarantees of basic legal and social protections.

Women’s rights advocates argued that if the federal government could define African American citizenship, it could also extend political rights to women.

Their petitions and court challenges exposed the limits of federal willingness to broaden citizenship and revealed inconsistencies in how equality principles were applied across different groups.

Although wartime measures expanded federal capabilities, maintaining such high levels of intervention proved politically contentious in peacetime.

Northern voters grew weary of military occupation and federal spending, while Southern resistance remained fierce.

As national priorities shifted, federal oversight weakened, allowing states to erode citizenship protections despite constitutional reforms.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Explain one way in which the Civil War expanded the power of the federal government.

Question 1

1 mark

• Identifies a valid way federal power expanded (e.g., conscription, suspension of habeas corpus, national taxation, issuance of greenbacks).

2 marks

• Provides a brief explanation showing how this action increased federal authority (e.g., conscription placed military manpower under national control rather than state control).

3 marks

• Offers clear elaboration connecting the expansion of federal power to wartime necessity or broader national authority, showing explicit understanding of the shift in state–federal balance.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Assess the extent to which Reconstruction succeeded in redefining American citizenship in the years immediately following the Civil War. In your answer, consider both expansions of rights and the limitations that remained.

Question 2

4 marks

• Identifies key developments that redefined citizenship (e.g., 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments; federal enforcement measures).

• Includes basic explanation of how these measures expanded rights for formerly enslaved people.

5 marks

• Provides a balanced argument showing both successes (e.g., legal abolition of slavery, birthright citizenship, voting rights) and limitations (e.g., violent resistance, weak federal enforcement, Supreme Court restrictions).

• Uses specific and accurate historical evidence.

6 marks

• Produces a well-reasoned assessment evaluating the degree of success, showing clear understanding of the contested and uneven nature of Reconstruction.

• Makes analytical connections between constitutional change, federal power, and practical outcomes in the South.