AP Syllabus focus:

‘Artists and critics—agrarians, utopians, socialists, and Social Gospel advocates—offered alternative visions for the economy and U.S. society.’

In the late nineteenth century, diverse reform thinkers challenged Gilded Age capitalism, proposing alternative economic, social, and moral visions to address inequality, corruption, and industrial society’s human costs.

Agrarian Critiques and Rural-Based Reform Thought

Agrarian reformers argued that industrial capitalism—particularly railroad monopolies, grain-elevator operators, and eastern financial interests—undermined the independence of small farmers. They promoted policies aimed at restoring economic fairness and protecting rural communities.

The Agrarian Ideal

Many rural reformers celebrated the agrarian ideal, the belief that an economy rooted in independent farmers safeguarded republican virtue.

Agrarian Ideal: A political and social philosophy asserting that small-scale, independent farmers form the most virtuous and stable foundation of a democratic society.

After introducing this ideal, farmers connected their critiques to the broader pressures of national agricultural markets, where falling crop prices and rising transportation costs destabilized livelihoods. As a result, agrarians promoted cooperatives, such as the Grange, to counterbalance corporate power.

Utopian Reform Visions

Utopian thinkers experimented with alternative social models designed to counteract the inequalities and alienation of industrial life. Drawing inspiration from earlier nineteenth-century reform traditions, they envisioned reorganized societies built on cooperation rather than competition.

Cooperative Communities

Some utopians advocated intentional communities in which property was shared, work was communal, and social harmony replaced market conflict. Although many experiments remained small-scale or short-lived, they represented critiques of mass production, wage labor, and concentrated wealth.

Edward Bellamy and “Looking Backward”

A major utopian critique emerged from Edward Bellamy’s 1888 novel Looking Backward, which imagined a future society that had eliminated poverty through national planning and collective ownership of industry.

This image shows a simple text-only cover of a 1919 German edition of Edward Bellamy’s Looking Backward: 2000–1887*. Although not the original 1888 American edition, it demonstrates the novel’s wide international reach and the continued influence of Bellamy’s utopian reform ideas. The German title provides additional historical context beyond the AP syllabus but effectively illustrates how the book circulated globally.* Source.

Bellamy argued that capitalist competition was inherently wasteful and unjust.

His ideas inspired Bellamy Clubs, where reformers debated nationalizing key industries.

The novel’s popularity reflected widespread frustration with Gilded Age inequality.

Bellamy’s vision stood as an influential counterpoint to the industrial capitalist order.

Socialist Critiques of Industrial Capitalism

Socialists advanced one of the most direct challenges to the Gilded Age economic system. They argued that private control of the means of production exploited workers and produced structural inequality.

Core Socialist Principles

Socialism: An economic and political philosophy advocating collective or public ownership of the means of production to ensure equitable distribution of wealth and reduce exploitation.

Socialists in the United States drew from European Marxist traditions but adapted them to American democratic institutions. They emphasized that concentrated corporate power threatened not only workers’ wages but also political equality.

After presenting these ideas, many socialist reformers sought alliances with organized labor, pushing for improved working conditions and public control of essential industries.

Socialist Influence in the Gilded Age

Although the socialist movement remained comparatively small in the nineteenth century, it:

Encouraged critiques of monopolies and trusts

Supported labor strikes by highlighting class conflict

Advocated municipal ownership of utilities, especially in urban centers

Their arguments contributed to broader debates about the responsibilities of government in regulating the economy.

Social Gospel Reform and Moral Critiques of Inequality

The Social Gospel movement responded to industrialization by applying Christian ethics to social problems such as poverty, labor exploitation, and urban dislocation.

Religious Reform and Social Responsibility

Social Gospel: A religious movement asserting that Christians had a duty to apply moral principles to improve social conditions and combat systemic inequality.

After defining this movement, it is clear that its leaders sought not only charitable aid but structural reform. Ministers like Washington Gladden and Walter Rauschenbusch argued that unchecked capitalism violated Christian teachings on justice and community.

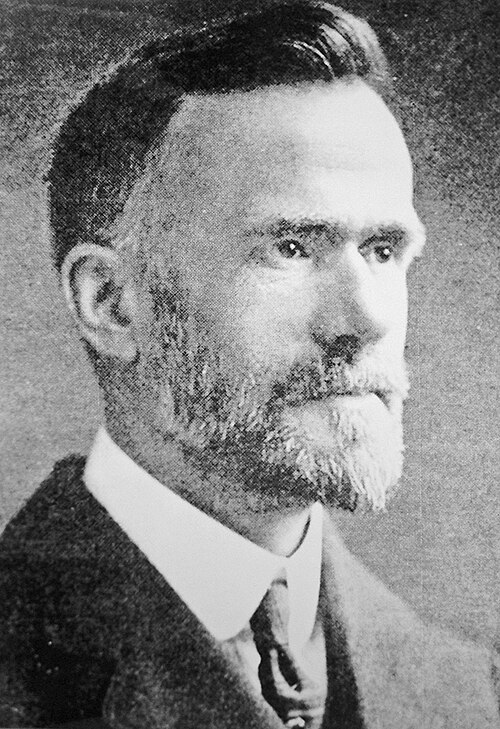

This formal portrait shows Walter Rauschenbusch, a Baptist theologian central to the Social Gospel movement. His work urged Christians to confront systemic poverty and labor exploitation rather than viewing inequality purely through individual morality. Although the photograph likely dates slightly after the core Gilded Age years, it accurately represents a major figure shaping reform-minded religious critiques of industrial capitalism. Source.

Key Themes of the Social Gospel

Social Gospel advocates promoted:

Living wages to ensure workers could support their families

Improved housing and sanitation in rapidly growing cities

Labor mediation to reduce conflict

Moral critiques of corporate behavior, especially in monopolistic industries

These ideas linked religious morality with calls for social and political change.

Intersections Among the Reform Currents

Despite differing ideological foundations, agrarians, utopians, socialists, and Social Gospel advocates shared several concerns about the Gilded Age:

Distrust of concentrated economic power

Critiques of the social costs of industrialization

Belief that alternative systems could promote greater equity and community well-being

Their overlapping critiques contributed to a growing national conversation about the appropriate direction of U.S. society during rapid industrial and economic transformation.

FAQ

Agrarian reformers argued that economic independence was essential for political independence. If farmers became dependent on railroads, banks, or monopolistic corporations, they believed democracy itself would weaken.

They viewed rural producers as the moral foundation of the nation and therefore claimed that policies favouring large trusts endangered not only livelihoods but also civic virtue and representative government.

Utopian writers worried about the loss of community cohesion and the impersonality of wage labour. Many believed that competition eroded social bonds and produced avoidable social conflict.

Common concerns included:

• The fragmentation of work into repetitive tasks

• The absence of cooperative structures

• The widening gulf between rich and poor

Such worries inspired visions of planned, communal, or cooperative societies as humane alternatives.

American socialism was generally less revolutionary, reflecting the country’s strong democratic traditions and suspicion of centralised authority.

Rather than advocating the overthrow of capitalism, many American socialists focused on:

• Municipal ownership of utilities

• Regulation or public control of monopolies

• Aligning with trade unions to improve working conditions

These tendencies made the movement more reformist than radical compared with its European counterparts.

Social Gospel advocates grounded their activism in the belief that Christian ethics demanded systemic, not merely charitable, solutions to inequality.

They promoted reforms such as:

• Settlements and missions in poor urban districts

• Advocacy for labour arbitration or living-wage principles

• Campaigns for improved housing, sanitation, and public welfare

Their strategy was to reshape society through institutions rather than rely solely on individual conversion.

Economic downturns exposed structural problems in the Gilded Age economy, making reform arguments more persuasive to the public.

During depressions, many Americans became more receptive to critiques of monopolies, labour exploitation, or moral failures of unregulated capitalism.

Consequently, reformers’ proposals gained visibility as people searched for explanations and alternatives capable of addressing unemployment, falling crop prices, and widening inequality.

Practice Questions

(1–3 marks)

Identify one way in which agrarian reformers criticised Gilded Age industrial capitalism. Briefly explain why this criticism emerged.

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Award up to 3 marks:

• 1 mark for identifying a valid agrarian criticism, such as opposition to railroad monopolies, high transportation rates, or financial dependence on eastern bankers.

• 1 mark for explaining why this criticism emerged, for example due to falling crop prices, economic instability, or the belief that industrial capitalism disadvantaged small farmers.

• 1 mark for demonstrating contextual understanding, such as noting wider economic consolidation or the shift towards national markets.

Maximum: 3 marks.

(4–6 marks)

Analyse how two of the following groups offered alternative visions for American society during the Gilded Age:

• Agrarians

• Utopians

• Socialists

• Social Gospel advocates

In your answer, explain how their critiques challenged mainstream economic or social structures.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Award marks as follows:

• 1–2 marks for describing each selected group’s core critique or reform vision (up to two groups). Answers may discuss agrarian demands for regulation and currency reform, utopian cooperative models, socialist calls for public ownership, or the Social Gospel’s moral critique of inequality.

• 1 mark for explaining how each group’s ideas challenged existing political, economic, or religious norms.

• 1 mark for using accurate contextual knowledge of the Gilded Age (e.g., industrial consolidation, labour conflict, urban poverty).

• 1 additional mark for comparative or analytical insight, such as noting similarities or differences between the reform groups or assessing their broader significance.

Maximum: 6 marks.