AP Syllabus focus:

‘Labor and management battled over wages and working conditions as workers organized local and national unions and confronted business leaders.’

Industrial expansion in the Gilded Age generated intense conflict between labor and management, as workers organized unions, launched strikes, and challenged the power of rapidly growing industrial corporations.

The Roots of Labor–Management Conflict

Rapid industrialization transformed work in the late nineteenth century. Factories grew in size, production scaled dramatically, and employers prioritized efficiency over worker autonomy. These conditions produced persistent struggles over wages, hours, and working conditions, motivating workers to form unions and pressure employers for reforms.

Industrial Working Conditions and Employer Control

Industrial capitalism relied on long hours, low pay, and dangerous environments, particularly in railroads, steel mills, and mines. Employees often faced wage cuts during economic downturns, while executives maintained strict control over labor through centralized management systems.

Workers commonly endured 10–12 hour days.

Mechanization reduced the need for skilled labor, lowering bargaining power.

Employers used blacklists, strikebreakers, and private security forces to suppress organizing efforts.

These tensions laid the foundation for organized labor movements seeking collective solutions to systemic workplace exploitation.

The Rise of Labor Unions

Workers turned to unions—local, craft-based, and national—to achieve leverage against powerful corporations. Unions varied in goals and structure but shared a belief in collective action as essential for negotiating with employers.

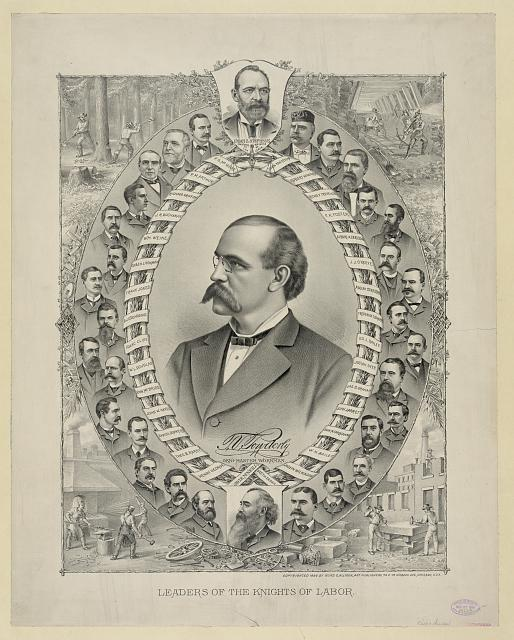

The Knights of Labor

Founded in 1869, the Knights of Labor brought together skilled and unskilled workers, women, and some Black workers into a broad reform coalition.

This lithograph presents major leaders of the Knights of Labor, emphasizing the national network of organizers who coordinated membership and strategy. The grouped portraits reflect the breadth of leadership supporting late-nineteenth-century labor reform. The image contains more figures than mentioned in the syllabus, but these additions help convey the movement’s scale. Source.

Term: Union — An organized association of workers formed to protect and advance their interests through collective bargaining and coordinated action.

The Knights advocated expansive reforms, including an eight-hour day and the end of child labor, while promoting cooperative ownership. Their inclusive membership offered a vision of labor solidarity that challenged existing economic hierarchies. However, their decentralized structure made coordination difficult.

The American Federation of Labor (AFL)

In 1886, craft unions formed the AFL, led by Samuel Gompers, focusing on skilled workers and “bread-and-butter” issues such as wages and working hours. Unlike the Knights, the AFL embraced pragmatic bargaining rather than sweeping social reform, strengthening its durability.

A normal sentence appears here to maintain flow before the next definition.

Term: Collective Bargaining — A negotiation process in which unions and employers establish agreements on wages, hours, and working conditions.

The AFL’s disciplined structure and limited goals made it more acceptable to employers and more effective in long-term negotiations.

Major Strikes and National Conflict

Strikes became central expressions of labor resistance, illustrating the escalating conflict between workers and industrial capitalists. Many escalated into national crises when federal or state authorities intervened on behalf of business.

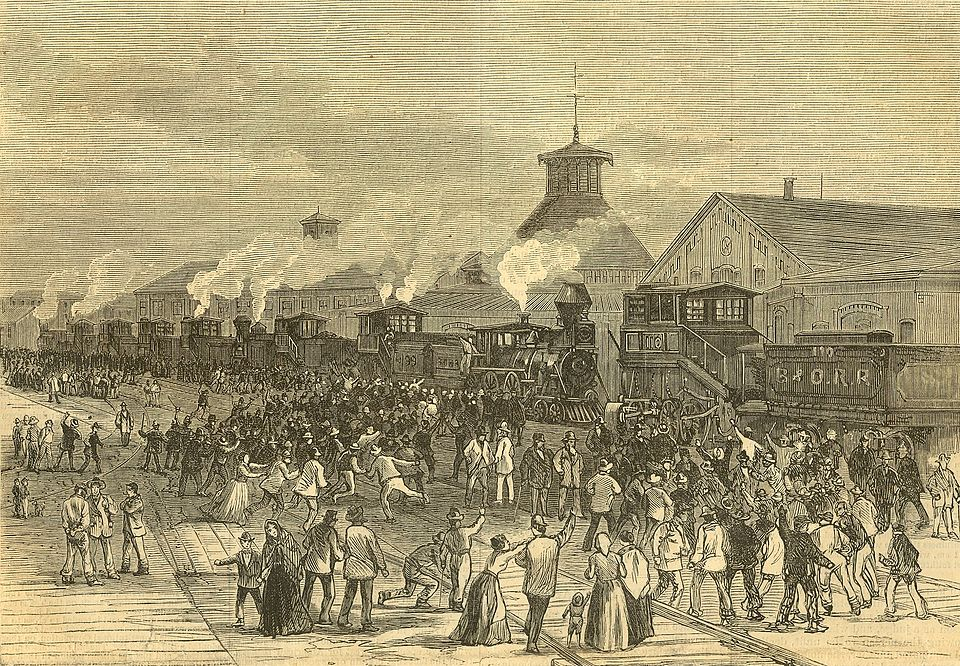

The Great Railroad Strike of 1877

Sparked by wage cuts during an economic depression, the Great Railroad Strike spread rapidly across multiple states.

This engraving depicts workers and townspeople halting several locomotives during the Great Railroad Strike of 1877. The presence of soldiers highlights how a wage dispute escalated into a national confrontation involving both labor and state force. Architectural and street details exceed the syllabus scope but support understanding the scale of the event. Source.

Workers halted rail traffic and clashed with militias. The federal government ultimately used troops to suppress the strike, signaling its willingness to defend corporate interests. The event convinced many workers that lasting change required stronger, more organized unions.

The Haymarket Affair (1886)

A rally in Chicago supporting the eight-hour day erupted into violence after a bomb killed several police officers. Newspapers blamed labor radicals and anarchists, leading to harsh public backlash.

The Knights of Labor were unjustly associated with the event.

Employers used Haymarket to portray union activism as dangerous.

Public fear weakened broader labor solidarity.

Haymarket marked a turning point by reshaping national attitudes toward labor activism and limiting momentum for sweeping reform.

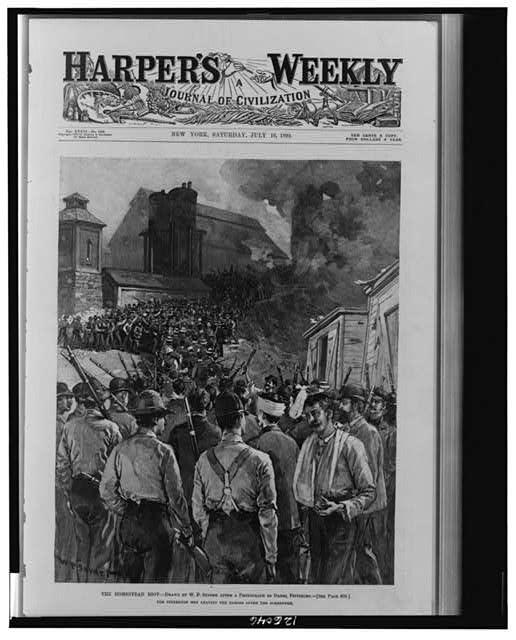

The Homestead Strike (1892)

At Andrew Carnegie’s Homestead Steel Works, a dispute over wage cuts led to a violent confrontation between locked-out workers and Pinkerton agents hired by management.

This engraving shows Pinkerton agents disembarking after their violent confrontation with strikers at Homestead in 1892. The crowded shoreline and armed guards illustrate the severity of labor–management conflict in heavy industry. Some background details exceed syllabus needs but enhance understanding of the event’s scale. Source.

The battle effectively broke the union at Homestead.

Management’s victory strengthened corporate authority in heavy industry.

Public opinion remained mixed, but many viewed unions as destabilizing.

The Pullman Strike (1894)

Triggered by wage reductions without rent relief in the company town, workers at the Pullman Palace Car Company joined the American Railway Union (ARU) under Eugene V. Debs. When rail traffic was disrupted nationally, the federal government intervened, citing interference with mail delivery.

Troops were deployed to end the strike.

Debs was arrested, and the ARU collapsed.

The event highlighted the federal government’s alignment with business interests.

Tools of Resistance and Employer Response

Labor–management conflict in the Gilded Age reflected unequal power dynamics. Employers deployed an array of tactics to maintain control.

Management Strategies

Lockouts to force workers into accepting terms.

Yellow-dog contracts requiring workers to avoid union membership.

Use of injunctions from sympathetic courts to halt strikes.

Replacement workers (“scabs”) to undermine picket lines.

These methods signaled a judicial and political environment that generally favored industrialists.

Labor’s Strategies

Strikes and boycotts to disrupt production and pressure employers.

Building nationwide networks among railroad, steel, mining, and factory workers.

Public campaigns to raise awareness about unsafe working conditions.

Despite limited victories, these strategies helped generate public debate about the rights of workers in an industrial economy.

Broader Impact on Gilded Age Society

Conflicts between labor and management during the Gilded Age shaped national discourse on economic power, the morality of wealth, and the responsibilities of government. Unions fostered new ideas about democracy in the workplace and challenged assumptions about the proper balance between corporate authority and worker rights. Even when unsuccessful, strikes exposed the vulnerabilities of industrial capitalism and inspired later Progressive Era reforms protecting workers and regulating business practices.

FAQ

Private security firms were frequently hired by employers to break strikes, guard property, and intimidate union organisers. Their presence often escalated conflicts that might otherwise have remained peaceful.

At Homestead in 1892, for example, Pinkerton agents attempted to retake the steelworks from striking employees, provoking gunfire and fatalities.

Their involvement demonstrated employers’ preference for force over negotiation and reinforced workers’ belief that the state and private power were aligned against organised labour.

Newspapers were often owned by business-friendly publishers who framed strikes as threats to order, prosperity, or patriotism.

Sensational headlines depicted strikers as radicals or criminals, particularly after events like the Haymarket bombing.

This coverage shaped middle-class attitudes, making it harder for unions to build broad support and allowing employers and governments to justify harsh anti-strike measures.

Skilled workers feared that inclusive unions would reduce their bargaining power by merging their interests with those of unskilled workers.

They also worried that broad reform agendas distracted from practical workplace issues such as pay, hours, and safety.

As a result, many gravitated towards craft unions and the American Federation of Labor, which limited membership and sought concrete, trade-specific gains.

Courts routinely issued injunctions against strikes, boycotts, and picketing, interpreting these activities as illegal restraints on commerce.

Judges tended to align with business interests, imposing fines or imprisonment on union leaders who defied orders.

This judicial hostility forced unions to adapt by limiting strike tactics, expanding legal defence strategies, and developing more structured collective bargaining approaches.

Communication networks for workers lagged behind those of employers, who had centralised administrative structures and telegraph networks.

Transport limitations, linguistic diversity among immigrant workers, and regional economic differences made shared strategy challenging.

Additionally, unions lacked consistent funding and depended heavily on volunteer organisers, limiting their ability to respond quickly to employer actions across multiple states.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Explain one reason why large-scale industrial strikes in the Gilded Age often resulted in intervention by state or federal authorities.

Question 1

Award up to 3 marks:

1 mark for identifying a valid reason for government intervention (e.g., disruption of rail traffic, threats to property, fear of radicalism).

1 mark for explaining how this reason motivated authorities to intervene (e.g., protecting economic interests, restoring order, maintaining mail delivery).

1 mark for linking the intervention to broader labour–management tensions (e.g., government siding with business interests, concern over violence and unrest).

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Using your knowledge of the period 1865–1898, evaluate the extent to which labour unions were successful in improving working conditions during the Gilded Age. In your answer, refer to specific unions and major strikes.

Question 2

Award up to 6 marks:

Up to 2 marks for describing unions’ aims and strategies (e.g., Knights of Labor’s inclusive programme, AFL’s focus on skilled workers and collective bargaining).

Up to 2 marks for using specific evidence from major strikes (e.g., Homestead Strike, Pullman Strike, Haymarket Affair) and explaining outcomes.

Up to 1 mark for assessing successes (e.g., raising national awareness, establishing foundations for later reform, some local gains in wages or hours).

Up to 1 mark for assessing limitations (e.g., frequent defeats, employer resistance, negative public opinion, government repression).

For a full 6 marks, answers should present a balanced, historically supported evaluation of the unions’ overall effectiveness.