AP Syllabus focus:

‘Civil rights progress was often slow, but activists achieved major legal and political successes and inspired broader movements for equality.’

Civil rights advances between 1945 and 1980 unfolded gradually, yet pivotal victories, grassroots activism, and shifting political strategies broadened the movement and inspired new campaigns for justice.

Slow but Significant Legal and Political Gains

The postwar era saw a combination of incremental legal progress, federal action, and grassroots organizing that pushed civil rights forward despite persistent opposition. Landmark rulings such as Brown v. Board of Education (1954) began dismantling Jim Crow segregation, while the federal government increasingly used its authority to enforce constitutional protections.

Key Milestones of Progress

Judicial victories weakened legal segregation and affirmed equal protection principles.

Executive authority expanded through desegregation orders, especially in the military and federal workforce.

Congressional action, including the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and Voting Rights Act of 1965, codified critical protections.

Mass protest movements created national pressure that reshaped public opinion and compelled political action.

Defining Core Concepts in Civil Rights Expansion

As civil rights movements grew, several foundational terms emerged that shaped strategy and ideology.

Civil Rights: The legal and political rights guaranteeing equal treatment and protection under the law for all citizens.

These rights were contested throughout the mid-20th century, requiring activists to blend courtroom litigation, mass mobilization, and political negotiation to achieve durable change.

After these gains, new movements drew lessons from the African American struggle, building broader campaigns for equality.

Federal Intervention and Its Limits

Although the federal government increasingly supported civil rights, its actions were often reactive and politically constrained. Presidents weighed moral leadership against Cold War concerns and domestic backlash, leading to selective enforcement.

Forms of Federal Action

Court rulings mandating desegregation.

Presidential orders, such as Truman’s military desegregation.

Legislation enforcing voting rights, equal access, and anti-discrimination measures.

Department of Justice suits targeting segregated institutions.

Federal power enabled structural change but could not eliminate entrenched racial inequality, prompting activists to continue pressuring institutions.

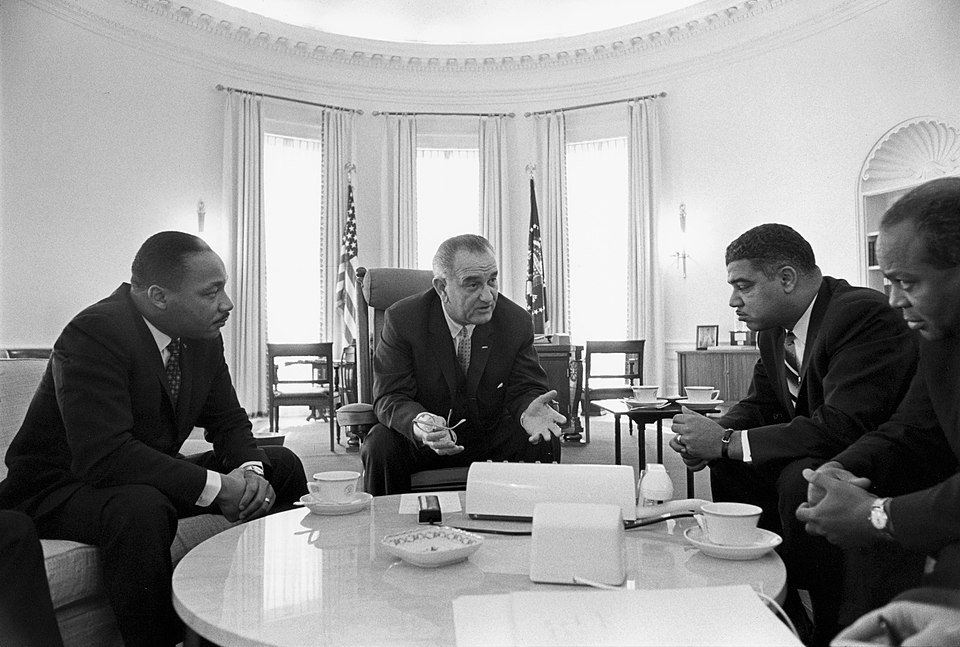

President Lyndon B. Johnson confers with civil rights leaders Martin Luther King Jr., Whitney Young, and James Farmer in 1964, highlighting coordination between grassroots activism and federal policymaking. The discussion reflects how protest and political access jointly shaped major civil rights legislation. While centered on national leadership figures, the scene illustrates limits and possibilities of federal intervention discussed in this subtopic. Source.

Grassroots Mobilization and Expansion of Nonviolent Protest

By the 1950s and 1960s, mass participation became central. Organizations such as the NAACP, SCLC, and SNCC mobilized local communities to challenge racial discrimination through nonviolent direct action.

Nonviolent Direct Action: Protest strategy using peaceful methods—such as sit-ins, marches, and boycotts—to expose injustice and pressure authorities without physical confrontation.

These tactics gained national attention, dramatizing segregation’s brutality and accelerating political change.

Fragmentation and New Directions After 1965

Even as landmark legislation passed, activists debated strategy. Many younger organizers, disillusioned by slow progress and continuing violence, embraced more militant rhetoric and demands for community control.

Shifting Strategies

Black Power advocates emphasized cultural pride, economic opportunity, and political autonomy.

Some activists questioned the effectiveness of strict nonviolence in the face of systemic inequality.

Conflicts over goals, leadership, and philosophy reflected the movement’s widening scope rather than its decline.

These debates broadened the landscape of civil rights activism and encouraged experimentation with new forms of political expression.

Inspired Movements and Expanding Claims to Equality

Successes in African American civil rights helped catalyze other mid-20th-century movements.

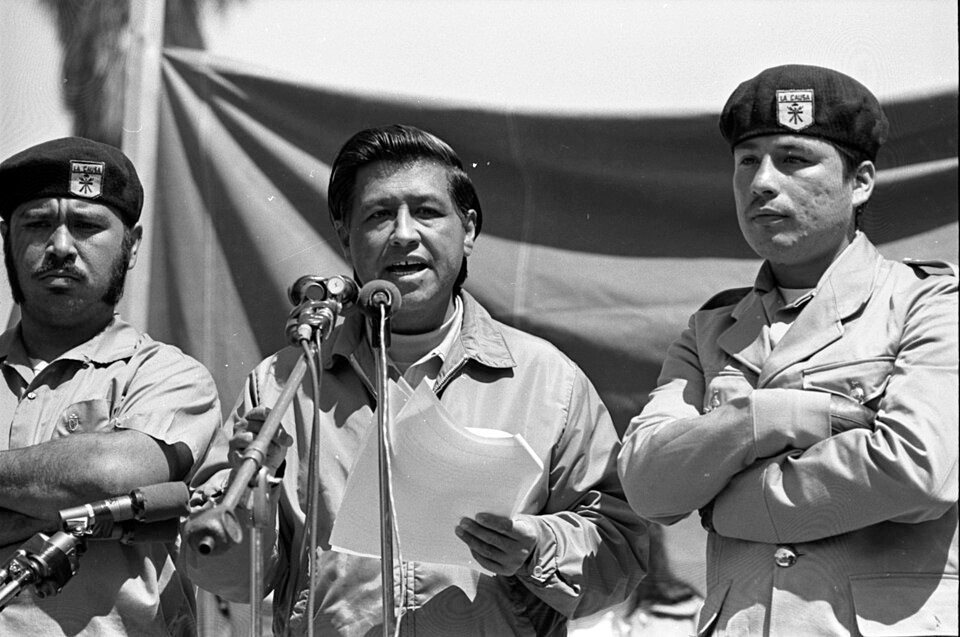

Cesar Chavez speaks at a 1971 peace rally alongside members of the Brown Berets, illustrating how Latino and Chicano activists adapted civil rights protest methods to pursue community empowerment and labor rights. The scene demonstrates how the African American movement inspired broader coalitions for justice. Although taken at an antiwar event, its themes mirror the interconnected activism of the period. Source.

Movements Drawing Inspiration

Latino and Chicano activists fought for labor rights, educational equity, and cultural recognition.

American Indian activists emphasized sovereignty and treaty enforcement.

Asian American communities organized against housing and employment discrimination.

Second-wave feminists demanded equal opportunity in work, education, and family life.

LGBTQ+ activists challenged legal restrictions and social stigma to pursue greater personal and civil liberties.

Intersectionality: The idea that multiple forms of discrimination—such as race, gender, and class—interact to shape individual experiences and social inequality.

This concept helped unite diverse movements by highlighting linked struggles against oppression.

Political Realignment and Backlash

As demands for equality surged, political polarization intensified. Some Americans embraced civil rights reforms, while others feared rapid social change. This tension fueled debates over federal authority, cultural values, and national identity.

Sources of Resistance

Southern opposition to desegregation.

Urban unrest intensifying calls for “law and order.”

Emerging conservative coalitions skeptical of federal intervention.

Despite backlash, civil rights activism profoundly reshaped American political life.

The Legacy of Expanding Movements

By the late 1970s, civil rights movements had transformed national expectations about equality, citizenship, and democracy. Their achievements—legal, cultural, and political—laid essential groundwork for ongoing struggles for justice across American society.

FAQ

Cold War competition often pushed the United States to present itself as a champion of democracy, which made racial inequality a diplomatic liability. This sometimes encouraged federal leaders to support civil rights measures to improve America’s global image.

However, concerns about national security also created suspicion toward activists, especially those criticised as disruptive or radical, slowing more transformative reforms.

Local campaigns created the conditions for national change by exposing injustices that federal leaders could no longer ignore.

Examples include:

• Community-led desegregation efforts in Southern towns

• Local boycotts and sit-ins that brought national media attention

• Grassroots voter registration drives revealing structural barriers

These initiatives demonstrated the persistence of inequality, helping drive federal legislative and judicial action.

Many younger activists felt that victories such as the Civil Rights Act and Voting Rights Act did not address deeper economic and social inequalities.

Key frustrations included:

• Police violence that persisted despite new laws

• Slow implementation of desegregation

• Limited federal support for addressing poverty and systemic discrimination

This disillusionment helped fuel interest in more assertive strategies such as Black Power.

As more groups adopted civil rights frameworks, citizenship increasingly came to include expectations of equal access to education, work, voting, and protection under the law.

These movements broadened national debates by insisting that democracy required full participation by all communities, challenging long-standing assumptions about who counted as a political subject.

Later movements adopted strategic models developed earlier, including coordinated leadership bodies, youth-focused wings, and locally rooted chapters.

They also replicated:

• Training in disciplined protest tactics

• Legal teams dedicated to pursuing court challenges

• National networks connecting local organisers

This organisational legacy helped new rights movements mobilise more effectively across diverse regions.

Practice Questions

(1–3 marks)

Identify one way in which African American civil rights activism between 1945 and 1965 inspired other minority movements in the United States.

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Award marks for the following:

1 mark

• Names a valid movement influenced by African American civil rights activism (e.g. Chicano Movement, American Indian Movement, Asian American activism, Second-Wave Feminism, LGBTQ+ rights activism).

2 marks

• Identifies a specific tactic, idea, or organisational method adopted from the African American movement (e.g. nonviolent direct action, legal challenges, community organising, mass protest).

3 marks

• Provides a brief explanation of how or why this influence occurred (e.g. Chicano activists used marches and boycotts similar to the Civil Rights Movement; Second-Wave feminists adapted the language of rights and equality promoted by African American activists).

(4–6 marks)

Explain how slow progress in early civil rights efforts contributed to the emergence of broader movements for equality by the late 1960s. Use specific historical examples in your answer.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Award marks for the following:

4 marks

• Describes at least two examples of slow or incomplete progress in the civil rights movement (e.g. persistent segregation, resistance to desegregation, uneven federal enforcement, economic inequality).

• Provides at least one example of a later movement that emerged partly in response to these limitations (e.g. Black Power, Chicano activism, American Indian sovereignty movements).

5 marks

• Explains the connection between slow progress and the rise of broader equality movements (e.g. frustration with limited gains encouraged more radical approaches; successes inspired other groups to pursue similar strategies).

• Uses specific, accurate historical details tied clearly to the period.

6 marks

• Offers a well-structured explanation showing clear causation.

• Integrates multiple specific examples (e.g. Brown Berets drawing on civil rights strategies, Black Power emphasising community control after perceived failures of nonviolence).

• Demonstrates strong contextual understanding of how African American activism set a precedent for national rights-based organising.