AP Syllabus focus:

‘Despite broad postwar affluence, poverty and unequal access to opportunity remained national issues that shaped debates over government policy.’

The postwar boom reshaped American society, yet shared prosperity masked continuing inequalities that raised urgent questions about opportunity, discrimination, and the role of government in promoting fairness.

Expanding Prosperity After 1945

The decades following World War II produced significant economic growth, driven by rising consumer demand, technological advances, and federal investment. Many Americans experienced unprecedented material comfort, and the middle class expanded as wages grew and unemployment stayed low.

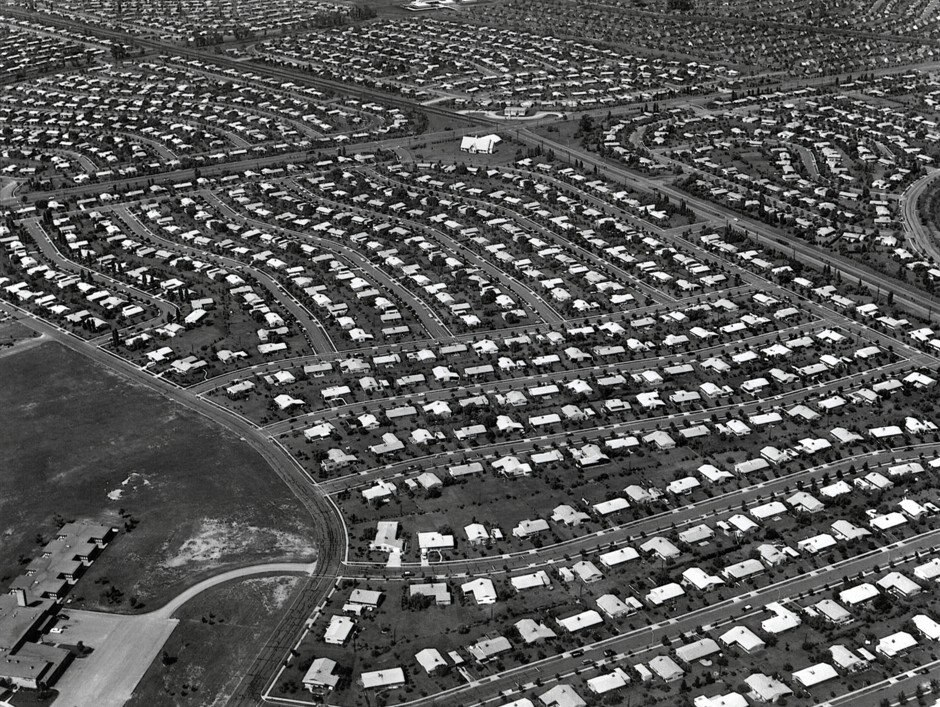

Aerial view of Levittown, Pennsylvania, one of the earliest and most famous postwar suburban developments, circa 1959. Rows of nearly identical houses and curving streets illustrate how mass-produced housing and automobile ownership made homeownership accessible to many white middle-class families. The image highlights the visible side of postwar prosperity that contrasted with the persistent poverty and inequality discussed in the notes. Source.

Engines of Postwar Growth

Several key forces sustained the booming economy and contributed to widespread optimism:

Federal spending on defense, infrastructure, and education stimulated long-term economic expansion.

Technological innovation, including advances in electronics, chemicals, and aviation, improved productivity and created new industries.

Mass consumerism encouraged Americans to buy homes, cars, and appliances, linking identity and citizenship to participation in the consumer economy.

Corporate expansion and stable labor-management agreements increased family incomes and stabilized many workers’ lives.

Persistent Poverty Within a Prosperous Nation

Despite these improvements, millions remained unable to access the benefits of postwar affluence.

President Lyndon B. Johnson shakes hands with a resident of Appalachia during his 1964 poverty tour, highlighting the severe rural poverty that persisted despite national prosperity. Scenes like this helped persuade Americans that economic growth alone could not eliminate hardship and that targeted federal intervention might be necessary. The image also anticipates later Great Society programs, which go beyond the precise scope of this subsubtopic but help students see how inequality shaped debates over government responsibility. Source.

Poverty persisted in both urban and rural areas, and many Americans experienced barriers rooted in race, region, and occupation. Influential social critics exposed these disparities, challenging triumphalist narratives about national abundance.

Poverty Line: A benchmark income level used by government agencies to determine whether individuals or families lack adequate resources for basic living needs.

Establishing measurable indicators such as a poverty line allowed policymakers to define the problem more precisely and exposed how growth alone did not guarantee equitable outcomes.

Unequal Access to Opportunity

Disparities emerged across multiple categories, revealing the limits of a booming economy to resolve long-standing inequalities.

Racial and Ethnic Inequality

Segregation and discriminatory practices limited access to good jobs, quality housing, and credit for many African Americans, Latinos, and other minority groups.

Redlining and exclusion from suburban mortgages reinforced residential segregation.

Workplace discrimination restricted advancement and depressed wages.

Unequal public schooling hindered long-term socioeconomic mobility.

Regional and Rural Disparities

The economic geography of the United States shifted unevenly.

Many Appalachian and rural Southern communities suffered from declining industries and entrenched poverty.

Migrant agricultural laborers, including many Mexican and Mexican American workers, faced low wages and poor living conditions.

Even as the Sun Belt expanded, pockets of severe deprivation persisted across the broader South and West.

Gendered Inequalities in a Prosperous Era

Postwar culture celebrated domesticity and defined women primarily through family roles, obscuring the economic challenges many faced.

Workplace norms permitted lower pay for women and limited their access to professional positions.

Married women’s labor was often informal or part-time, leaving them especially vulnerable to economic instability.

Cultural expectations shaped hiring decisions, reinforcing inequality despite rising workforce participation among women.

Urban Transformation and New Forms of Inequality

Urban centers experienced dramatic changes during the postwar period that heightened economic divides.

Middle-class suburbanization drained cities of tax revenue, contributing to declining public services.

Urban renewal projects displaced low-income residents, disproportionately affecting minority communities.

Razed houses and cleared lots in the Triangle section of Charleston, West Virginia, during a 1973 urban renewal project. The image shows how renewal often meant demolition of older housing stock in low-income neighborhoods, displacing residents rather than simply improving their living conditions. The photograph comes from an EPA environmental documentation project, so it also includes a concern with land use and environmental impacts that extends slightly beyond the specific syllabus focus on inequality. Source.

Public housing initiatives frequently reinforced segregation patterns and concentrated poverty.

Together, these forces intensified debates over the proper scope of federal and municipal responsibility in managing urban inequality.

Policy Responses and Debates Over Government Responsibility

As awareness of persistent inequality grew, Americans sharply disagreed over how government should address the issue. Policymakers, intellectuals, and citizens debated whether prosperity alone would eventually lift disadvantaged groups or whether targeted federal intervention was essential.

Expanding Federal Attention to Poverty

By the 1950s, several developments pushed poverty into national conversation:

Journalists and scholars published influential works revealing that millions were “left behind” despite national affluence.

Early federal programs, such as expanded Social Security coverage and housing initiatives, attempted to ease disparities.

Growing Cold War competition encouraged policymakers to view domestic inequality as a weakness that undermined the nation’s global image.

Contested Visions of Economic Opportunity

Debates over government action centered on two competing frameworks:

Advocates of intervention argued that structural barriers—racism, regional neglect, and unequal schooling—required federal investment and oversight.

Critics maintained that federal involvement distorted free-market principles and encouraged dependency, insisting that economic growth and individual initiative were sufficient solutions.

These disagreements foreshadowed the more expansive programs of the Great Society in the 1960s as well as the conservative challenges to those programs in the 1970s.

The Significance of Inequality in an Age of Affluence

Persistent poverty and unequal opportunity became central issues shaping federal policy, social movements, and public debate throughout the postwar era. While prosperity defined national identity, inequality forced Americans to confront unresolved questions about fairness, citizenship, and the meaning of the American Dream in a rapidly changing society.

FAQ

Researchers, journalists, and social critics increasingly argued that poverty persisted not because of individual failings but because of structural barriers based on race, geography, and access to education.

Their work reframed poverty as a national challenge requiring systematic attention, contrasting sharply with the dominant public narrative of widespread postwar prosperity.

Groups such as Native Americans, migrant labourers, and urban ethnic minorities were often excluded from national narratives because government data collection focused primarily on industrial workers and suburban households.

Their economic hardship was further obscured by geographic isolation, limited political influence, and the lack of sustained media coverage.

Consumer culture linked citizenship to purchasing power, which amplified existing disparities.

Families with stable wages could participate fully in mass consumption.

Those facing discrimination or low-wage work were priced out of homeownership, car ownership, and new appliances.

Marketing campaigns overwhelmingly targeted white suburban consumers, normalising unequal access as part of the cultural landscape.

Population movements, including suburban migration and growth in the Sun Belt, redistributed wealth unevenly.

Rural and inner-city communities experienced declining tax bases, deteriorating public services, and limited investment, deepening structural disadvantages for people who remained in those areas.

Councils often prioritised development strategies that favoured business interests and suburban growth, while neglecting older neighbourhoods.

Policies such as zoning restrictions, school district boundaries, and targeted infrastructure development reinforced segregation and unequal service provision, even without explicit discriminatory language.

Practice Questions

Explain one reason why poverty persisted in the United States despite broad postwar economic prosperity after 1945. (1–3 marks)

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Award up to 3 marks.

1 mark for identifying a valid reason (e.g., structural racial discrimination).

1 mark for explaining how this factor limited access to prosperity (e.g., segregation restricted access to well-paid jobs and quality housing).

1 mark for placing the explanation within the postwar context (e.g., despite economic growth and suburban expansion, minority communities continued to face systemic barriers).

Maximum: 3 marks.

Assess the extent to which postwar affluence contributed to debates over the federal government’s responsibility in addressing inequality between 1945 and 1960. (4–6 marks)

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Award up to 6 marks.

1–2 marks for describing postwar affluence and its uneven distribution (e.g., expansion of the middle class, consumer culture, persistent poverty in rural and urban areas).

1–2 marks for explaining how these conditions fuelled debates about federal responsibility (e.g., arguments for targeted intervention versus reliance on market forces).

1–2 marks for evaluative judgement addressing “the extent to which” (e.g., showing that prosperity both revealed and obscured inequality, prompting limited early federal action but substantial public debate).

Maximum: 6 marks.