AP Syllabus focus:

‘Artists and critics challenged mainstream culture and Cold War anxieties, helping inspire new cultural styles and dissenting viewpoints.’

Postwar prosperity and Cold War tension produced a dynamic cultural landscape in which artists, writers, and youth movements critiqued conformity, sparking early countercurrents that challenged dominant American values.

Cultural Critiques and Early Countercurrents

American culture after 1945 appeared outwardly unified, shaped by mass media, consumerism, and heightened Cold War patriotism. Yet underneath this mainstream consensus, diverse groups questioned established norms, challenging political assumptions, social expectations, and cultural uniformity. Their critiques laid the groundwork for later counterculture movements of the 1960s.

The Cultural Climate of the Early Cold War

Cultural dissent developed in a climate defined by anti-communism, expectations of social conformity, and rapid expansion of mass culture. Many Americans embraced suburbanization, television, and consumer goods as symbols of stability. However, intellectuals and artists found these trends stifling and warned that uniformity threatened creativity and democratic expression.

The Beat Generation and Literary Rebellion

The Beat Generation, a loose circle of writers in the 1950s, became one of the earliest and most influential countercurrents to mainstream culture.

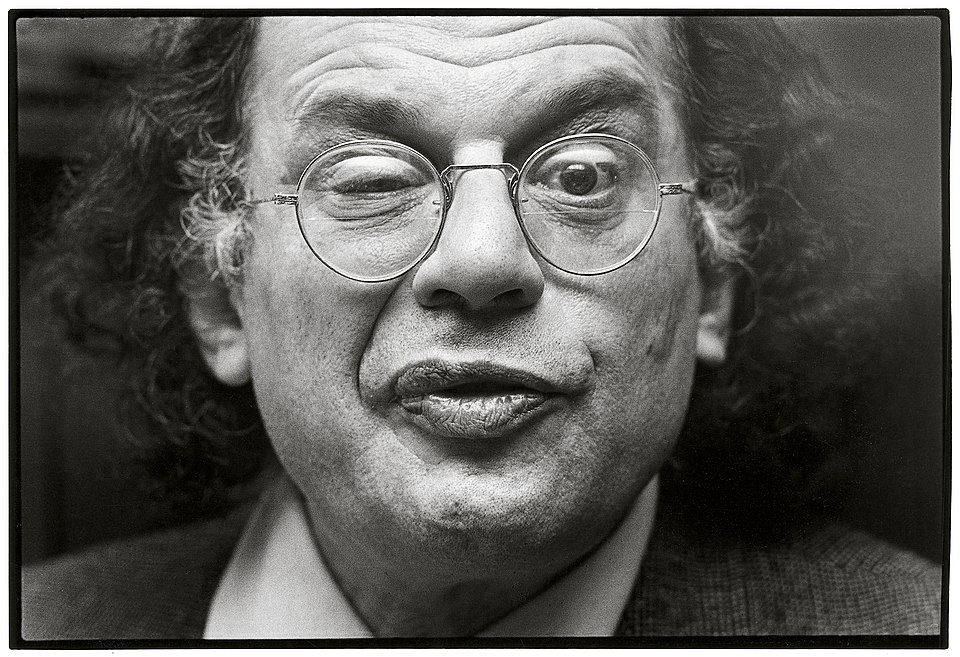

Allen Ginsberg, a leading Beat poet, became an emblem of postwar cultural dissent through writing that criticized conformity and celebrated personal freedom. Images like this help connect Beat literature to the broader climate of Cold War-era cultural critique. Source.

Authors such as Allen Ginsberg, Jack Kerouac, and William S. Burroughs rejected materialism, suburban domesticity, and Cold War moral rigidity. Their works emphasized spontaneity, nonconformity, and exploration of individual freedom.

Nonconformity: The rejection of established norms, behaviors, or expectations in favor of independent expression or alternative lifestyles.

Beat literature challenged ideals of respectability by incorporating themes of sexuality, spirituality, and political critique. Their public readings and travels created communities that valued artistic experimentation over middle-class stability.

Abstract Expressionism and Artistic Innovation

In the visual arts, Abstract Expressionism emerged as a powerful critique of both totalitarian control abroad and cultural conformity at home. Artists such as Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko, and Willem de Kooning used nonrepresentational forms and expressive techniques to emphasize individual emotion and creative autonomy. Their work aligned with democratic ideals by highlighting personal freedom, yet it also resisted commercialization and formulaic artistic norms.

Artists questioned whether mass-produced culture diluted the meaning of art. This critique helped shift the United States into a global artistic center, challenging older European dominance while fostering new debates about the relationship between art, politics, and identity.

Music, Youth Culture, and the Seeds of Dissent

Music also provided space for challenging mainstream values. Early rock and roll, shaped by African American musical traditions, unsettled adults who associated it with rebellion and social boundary-crossing. Performers such as Elvis Presley complicated norms surrounding sexuality, race, and generational authority.

For many young people, popular music became a channel for expressing dissatisfaction with rigid gender expectations, Cold War anxieties, and racial segregation. Although not yet a cohesive political movement, youth culture increasingly distanced itself from postwar conformity.

Cold War Anxiety and Nuclear-Age Criticism

Cultural critiques often reflected fear of nuclear war and concerns about governmental authority.

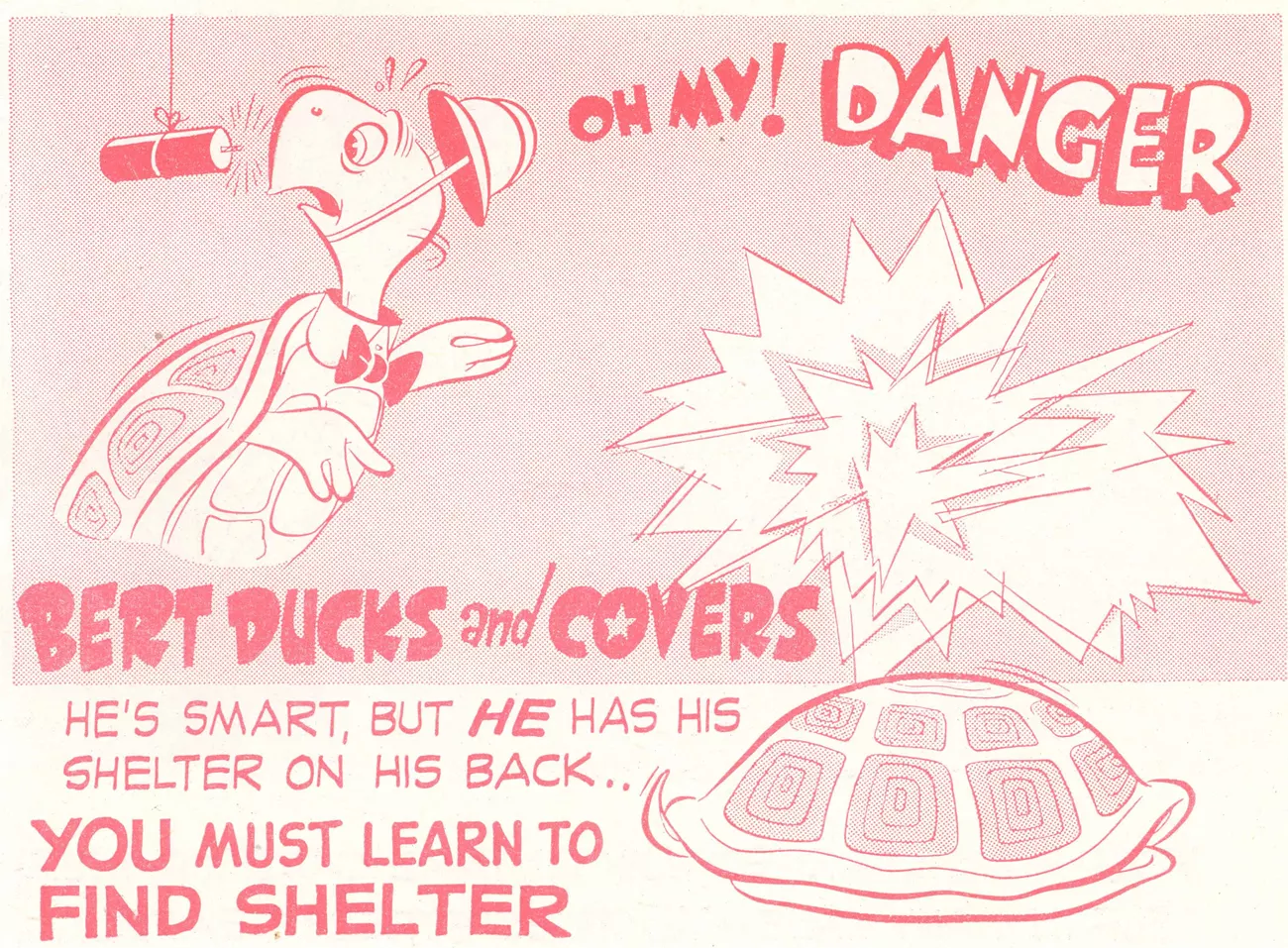

This civil defense illustration from the “Duck and Cover” campaign shows how the U.S. government communicated nuclear preparedness to children using simplified, reassuring imagery. The source page also discusses wider civil defense issues beyond the syllabus, but the image accurately captures Cold War-era nuclear anxiety. Source.

Writers, filmmakers, and scholars warned that the arms race and national-security culture encouraged secrecy, repression, and unquestioning patriotism. Science-fiction films depicted alien invasions or dystopian futures as metaphors for loss of individuality and the dangers of authoritarianism.

Dystopia: A fictional or imagined society characterized by oppression, loss of freedom, or extreme social control.

These works questioned whether defending democracy abroad justified limiting dissent or civil liberties at home. They also contributed to a broader public conversation about the moral implications of nuclear strategy.

Early Challenges to Gender and Family Norms

While suburban family ideals dominated the postwar years, some critics highlighted their limitations. Feminist thinkers such as Betty Friedan—whose later work built on earlier observations—argued that suburban domesticity often confined women to narrowly defined roles. Female authors and artists explored themes of identity, autonomy, and dissatisfaction with cultural expectations.

At the same time, some men critiqued the pressures of the corporate workplace, which demanded conformity and emotional restraint. These early voices questioned whether postwar prosperity truly expanded personal fulfillment or simply reshaped social constraints.

Roots of Later Counterculture Movements

The critiques of writers, artists, musicians, and intellectuals did not yet form a unified movement, but collectively they challenged Cold War consensus culture. Their focus on authenticity, emotional depth, and personal liberation offered alternatives to the values promoted by mass media and political leaders.

These early countercurrents provided ideological and stylistic foundations for the more expansive dissent of the 1960s. They encouraged young Americans to question authority, experiment with new cultural forms, and explore identities beyond the narrow expectations of postwar society.

FAQ

Widespread pressure to demonstrate loyalty and patriotic unity encouraged Americans to adopt uniform social behaviours, including conventional family structures and consumer habits.

This atmosphere pushed artists, writers, and young people to seek alternative forms of expression that rejected predictability and emphasised individuality.

Early countercurrents arose partly as a reaction to the fear that conformity weakened democratic creativity and limited personal freedom.

Cities such as New York and San Francisco offered diverse communities, inexpensive living arrangements, and vibrant artistic networks.

These settings allowed writers, painters, and performers to collaborate informally and share ideas that challenged conventional culture.

Urban cafés, jazz clubs, and loft studios became informal incubators for early countercultural experimentation.

Analysts argued that television and advertising promoted passive consumption rather than critical thinking.

They believed mass media encouraged standardised tastes that weakened regional and class-based cultural diversity.

For some, the concern centred on how mass-produced entertainment could be used to reinforce political consensus during the Cold War.

Although not overtly political at first, early movements introduced themes that resonated with the next generation.

Key influences included:

• Emphasis on personal authenticity

• Distrust of authority and rigid institutions

• Interest in non-Western spiritual traditions

These ideas helped shape the tone and outlook of youth activism in the early 1960s.

Jazz musicians, particularly those in experimental or avant-garde circles, challenged musical conventions through improvisation and unconventional structures.

Their innovations symbolised artistic freedom at a time when cultural conformity was widespread.

Some performers used their work to comment indirectly on social tensions, including racial discrimination and Cold War pressures.

Practice Questions

Describe one way in which the Beat Generation challenged mainstream American culture in the 1950s. (1–3 marks)

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

• 1 mark: Identifies a valid aspect of Beat counterculture (e.g., rejection of materialism, criticism of conformity, experimentation with new literary styles).

• 2 marks: Provides a clear description showing how this challenged mainstream values.

• 3 marks: Offers developed explanation with specific reference to a Beat writer, work, or characteristic attitude (e.g., Ginsberg’s critique of Cold War morality).

Explain how cultural critiques and early countercurrents in the 1950s reflected broader Cold War anxieties. In your answer, refer to at least two different groups or artistic movements. (4–6 marks)

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

• 1–2 marks: Basic explanation of Cold War anxieties and brief reference to one cultural critique or movement.

• 3–4 marks: Clear explanation connecting at least two cultural movements (e.g., Abstract Expressionists and Beat writers) to Cold War fears such as nuclear threat, conformity, or suppression of dissent.

• 5–6 marks: Developed, well-organised analysis demonstrating how these movements expressed anxiety about authority, individuality, or repression, with accurate supporting examples (e.g., Pollock’s emphasis on personal freedom; dystopian themes in literature and film).