AP Syllabus focus:

‘Assess how technological innovation, rising productivity, and the decline of manufacturing changed daily life, work patterns, and Americans’ sense of opportunity.’

Rapid technological innovation after 1980 reshaped American work, identity, and expectations, as digital tools, automation, and economic restructuring transformed productivity, employment patterns, and perceptions of opportunity nationwide.

Technology and the Restructuring of the American Economy

Technological change in the late 20th and early 21st centuries fundamentally altered how Americans worked and imagined their futures. The expansion of computing, mobile digital technology, and the internet created an information economy, shifting national priorities away from heavy industry toward service-centered and knowledge-based fields. These developments accelerated productivity while weakening traditional employment anchors that had defined earlier generations.

Information Economy: An economic system in which knowledge, data processing, and digital technologies drive growth rather than industrial manufacturing.

As digital tools expanded, firms increasingly relied on software, data management, and automated processes to improve efficiency. This transformation supported new entrepreneurial ventures, global connectivity, and rapid communication, reshaping business operations and competitive standards. At the same time, many Americans confronted an uneven distribution of benefits, as gains from technological productivity did not uniformly translate into higher wages or improved job security.

Automation and the Decline of Manufacturing Work

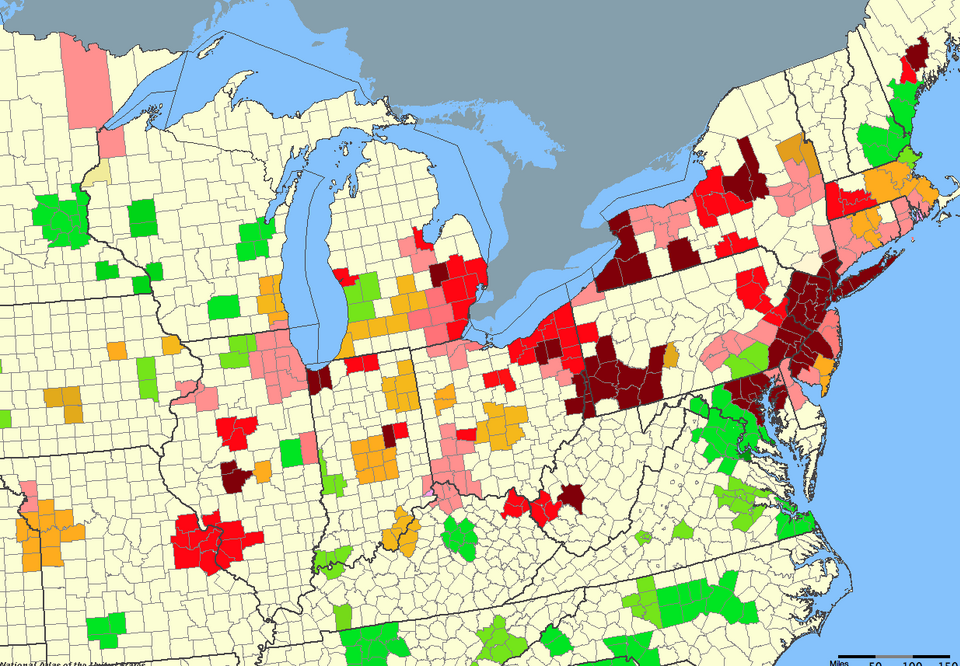

Automation and globalization reduced the demand for industrial labor, especially in regions once anchored by factories. By the 1990s and 2000s, many firms had adopted robotic manufacturing, computerized logistics, and lean production methods, minimizing the need for large numbers of skilled and unskilled workers. Communities in the Rust Belt experienced sustained economic disruption as factories downsized or relocated overseas.

This map illustrates uneven regional impacts of manufacturing decline, with the Rust Belt showing the steepest job losses. It highlights how deindustrialization created long-term economic strain in affected communities. The timeline predates 1980 but clarifies the historical trajectory leading to post-1980 disruptions. Source.

Automation: The use of machines, robotics, or computer-controlled systems to perform tasks previously carried out by human labor.

Even as automation made production faster and more consistent, its expansion generated widespread debate over the future of work and the nation’s responsibility to displaced workers. The decline of union membership further weakened labor’s bargaining power, reducing wages and benefits for many working-class Americans. These changes contributed to long-term wage stagnation and shaped new political and cultural anxieties around job loss, economic inequality, and fairness.

The Rise of Service and Knowledge-Based Work

While manufacturing contracted, employment grew in healthcare, education, finance, technology services, and other sectors requiring specialized training or digital proficiency. Workers increasingly needed postsecondary education or technical certifications to secure stable careers. This shift altered understandings of class identity, encouraging a cultural emphasis on adaptability, lifelong learning, and human capital development.

Human Capital: The skills, knowledge, and experience possessed by individuals that enhance their economic productivity and employability.

New work patterns emerged as well. Telecommuting, remote collaboration, and digital project management became commonplace with the rise of personal computers and broadband internet. These technologies allowed businesses to outsource tasks globally and adopt flexible scheduling systems. Many Americans appreciated the greater autonomy and creativity possible in information-age fields, while others struggled with unstable hours, contract work, and the erosion of traditional career ladders.

How Technology Transformed Daily Life

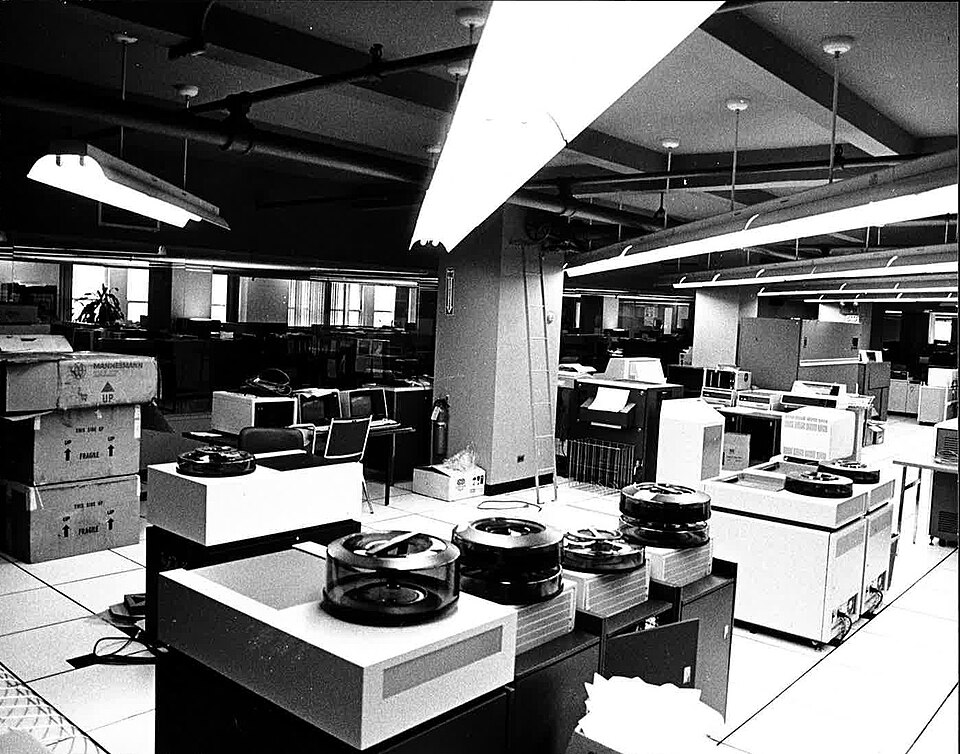

Technological innovation reached deeply into everyday routines. The widespread adoption of personal computers, mobile phones, and eventually smartphones expanded access to information and reshaped communication.

This photograph shows how computer systems entered office environments in the early Information Age, transforming clerical and administrative work. It illustrates the technological foundation that later enabled personal computing and mobile connectivity. Although it predates smartphones, it captures a pivotal stage in workplace digitization. Source.

Americans could shop online, maintain social networks across long distances, and access entertainment instantly. Digital navigation, email, and search engines fundamentally changed how individuals interacted with institutions, public services, and one another.

These shifts also carried profound social implications:

Changing family dynamics: Digital tools made work more portable, blurring boundaries between home and workplace.

Cultural fragmentation: Online platforms allowed people to form niche communities, but also exposed them to misinformation and ideological polarization.

New forms of identity: Social media enabled self-presentation, activism, and connection, redefining how individuals imagined their roles in society.

Productivity Gains and Unequal Outcomes

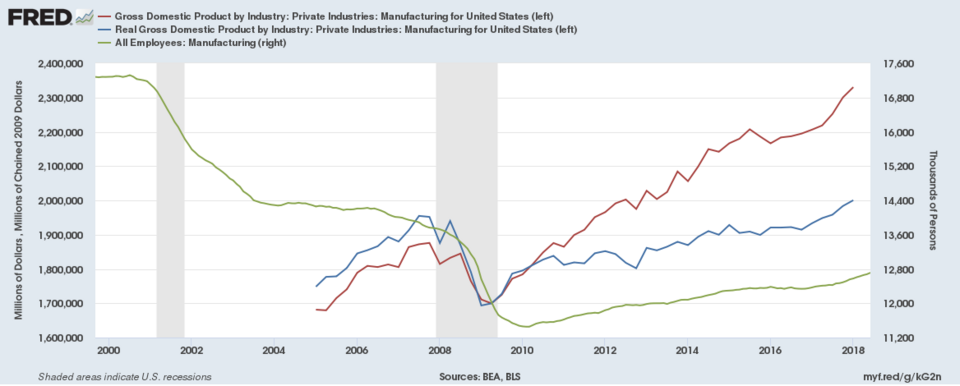

Technological innovation significantly raised economic productivity, allowing businesses to produce more with fewer inputs.

This graph demonstrates how U.S. manufacturing output increased while employment declined, reflecting rising productivity driven by technological change. It reinforces the disconnect between economic growth and job availability. The long-term trend contextualizes post-1980 wage stagnation and structural shifts in labor demand. Source.

Yet many workers did not see proportional improvements in wages. Middle- and working-class Americans experienced stagnant real income even as the technology sector generated immense wealth. This divergence contributed to a growing sense that opportunity was increasingly linked to geography, education, and technological access.

Key consequences included:

Economic inequality: Concentrated in booming metro areas such as Silicon Valley and Seattle.

Regional disparity: Rural and deindustrialized communities often lacked high-tech employment pathways.

Political realignment: Economic frustration fueled debates over globalization, trade, and federal economic policy.

Technology, Work, and Evolving National Identity

By the early 21st century, technology had reshaped American identity as profoundly as earlier industrial revolutions. Work was no longer solely a matter of physical labor or factory production; instead, it involved digital literacy, continuous adaptation, and global interconnection. Many Americans embraced these developments as evidence of national innovation and entrepreneurial strength. Others perceived them as sources of insecurity, cultural change, and diminished control over economic destiny.

FAQ

The commercial spread of the internet allowed businesses to streamline communication, expand markets, and adopt faster decision-making structures.

It encouraged flatter workplace hierarchies, as employees could collaborate across departments and locations with unprecedented speed.

• Customer service, sales, and technical support increasingly moved online, creating new job types tied to digital fluency.

• Start-ups and small firms found it easier to scale, reinforcing a culture that valued innovation and entrepreneurial risk.

Many employers introduced in-house training in computer literacy, database management, and emerging software tools.

These programmes aimed to minimise skill gaps that could slow adoption of new technologies and reduce productivity.

They also helped normalise lifelong learning, framing professional development as an ongoing expectation in an economy where technologies changed rapidly.

Digital tools enabled more detailed monitoring of employee performance, such as tracking keystrokes, workflow speed, or customer-service metrics.

This increased managerial oversight while simultaneously expanding opportunities for employee autonomy through remote work options.

The result was a dual dynamic: greater flexibility for many workers, paired with more intensive productivity expectations.

Regions with strong research universities, venture capital networks, and existing technical infrastructure—such as Silicon Valley and Boston—were well positioned to attract high-tech firms.

Access to skilled labour reinforced a cycle of growth, as companies clustered where specialised talent was abundant.

Areas lacking these assets struggled to transition away from manufacturing, widening geographic disparities in opportunity.

The rapid expansion of technology careers created a belief that digital skills could unlock upward mobility, especially for younger cohorts entering the workforce in the 1990s and 2000s.

However, rising educational requirements and competition for high-wage tech jobs led to a perception that opportunity was increasingly concentrated among those with advanced qualifications.

This tension shaped debates about inequality, access to higher education, and the affordability of technical training.

Practice Questions

(1–3 marks)

Identify and briefly explain one way in which technological innovation after 1980 altered patterns of work for American employees.

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

1 mark: Identifies a valid change (e.g., increased automation, growth of remote work, shift to service-sector jobs, need for digital skills).

2 marks: Provides a brief explanation of how this change altered work patterns (e.g., automation reducing factory jobs, digital tools enabling telecommuting).

3 marks: Offers a clear and accurate link between technological innovation and its impact on daily work, showing a basic understanding of the broader economic shift.

(4–6 marks)

Assess the extent to which the decline of manufacturing and the rise of a service- and knowledge-based economy after 1980 reshaped Americans’ sense of opportunity. Use specific evidence to support your answer.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

4 marks: Provides a generally accurate explanation of how economic restructuring affected Americans’ sense of opportunity, referencing at least one specific development (e.g., decline of the Rust Belt, rise of technology hubs, growing need for education and skills).

5 marks: Includes multiple accurate examples and shows an understanding of both opportunities (e.g., new tech careers, productivity gains) and limitations (e.g., wage stagnation, regional inequality).

6 marks: Presents a well-developed assessment that weighs the extent of change, integrates clear historical evidence, and directly evaluates how these transformations influenced differing experiences across social or geographic groups.