AQA Specification focus:

‘Rational economic decision making and economic incentives; utility maximisation; the importance of the margin when making choices.’

Rational decision making in economics assumes individuals make choices that maximise their satisfaction, using incentives and marginal reasoning to allocate scarce resources efficiently.

Rational Economic Decision Making

In traditional economics, individuals are assumed to be rational economic agents who aim to make choices that maximise their utility (satisfaction or benefit). This process involves weighing up the costs and benefits of different options to achieve the greatest net gain.

Rational economic agent: An individual who makes decisions aimed at maximising their utility based on available information.

Rational decision making relies on:

Clear objectives: Knowing what the individual wants to achieve.

Full information: Access to accurate and relevant data about alternatives.

Consistent preferences: Choices remain logically aligned over time.

However, in reality, these conditions are rarely perfectly met due to imperfect information and cognitive limitations, though the model remains a useful analytical benchmark.

Economic Incentives

Incentives are factors that motivate or influence behaviour and decision making. They can be:

Financial (e.g., wages, prices, subsidies)

Non-financial (e.g., social recognition, personal fulfilment)

Economic incentive: A factor that influences the choices of individuals, firms, or governments by altering the costs or benefits of an action.

Incentives shape the decision-making process by influencing the relative attractiveness of different options. For example, a price reduction increases the incentive for consumers to purchase a product.

Positive vs Negative Incentives

Positive incentives encourage certain behaviour (e.g., tax cuts for investment).

Negative incentives discourage certain behaviour (e.g., fines for pollution).

Governments and businesses design incentive structures to guide decisions towards desired outcomes, such as promoting employment or reducing harmful activities.

Utility Maximisation

Utility represents the satisfaction gained from consuming goods or services. Rational consumers aim to allocate their income to achieve the highest possible total satisfaction.

Utility maximisation: The process of allocating resources to obtain the greatest total satisfaction possible from consumption.

Key aspects of utility maximisation include:

Choosing combinations of goods that yield the highest total utility given a budget constraint.

Considering the marginal benefit of each additional unit consumed.

Adjusting consumption patterns when relative prices change to maintain maximum satisfaction.

While traditional theory assumes consumers are motivated solely by utility maximisation, behavioural economics recognises that social norms, fairness, and biases can also influence choices.

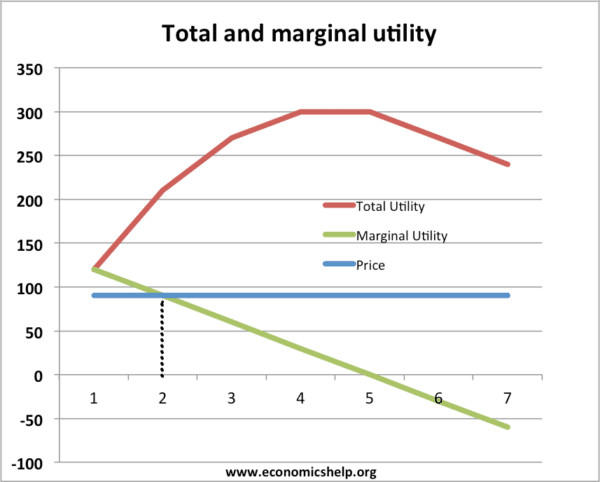

This graph depicts the relationship between total utility and marginal utility. As total utility increases, marginal utility decreases, illustrating the law of diminishing marginal utility. This concept explains why consumers are willing to purchase more of a good only if its price decreases, supporting the downward-sloping demand curve. Source

The Importance of the Margin in Decision Making

Marginal reasoning is central to rational economic choice. Decisions are not based solely on total benefits or costs, but on the additional (marginal) benefit or cost of a small change in activity.

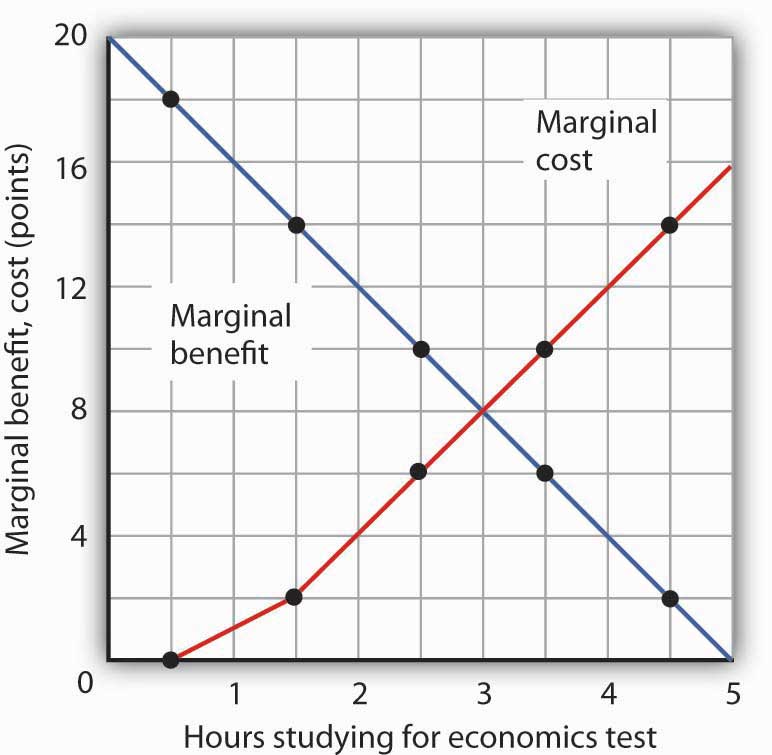

Marginal analysis: The comparison of the additional benefits and additional costs of a decision to determine the optimal level of an activity.

Marginal Benefit (MB) = Change in Total Benefit ÷ Change in Quantity

MB = Additional satisfaction gained from consuming one more unit.

Marginal Cost (MC) = Change in Total Cost ÷ Change in Quantity

MC = Additional cost incurred from producing or consuming one more unit.

Rational decision makers will continue an activity up to the point where marginal benefit equals marginal cost (MB = MC), which represents the optimal allocation of resources.

This diagram illustrates the concept of marginal analysis, where rational decision-makers continue an activity until the marginal benefit equals the marginal cost. The intersection point represents the optimal allocation of resources, guiding efficient decision-making in economics. Source

Applications of Marginal Reasoning

Consumers decide how much of a good to buy based on whether the extra satisfaction justifies the cost.

Firms decide how much to produce depending on whether the revenue from the next unit exceeds its production cost.

Governments evaluate whether the additional benefits of a public policy justify the extra expenditure.

Linking Marginal Reasoning to Utility Maximisation

The law of diminishing marginal utility states that as more of a good is consumed, the additional satisfaction from each extra unit decreases. This means:

Consumers allocate spending to equalise marginal utility per pound across goods.

The downward-sloping demand curve can be explained by falling marginal utility: consumers are only willing to buy additional units if the price falls.

Marginal analysis thus connects consumer behaviour to market demand and underpins many microeconomic models.

The Role of Opportunity Cost in Rational Decision Making

Every decision involves opportunity cost — the value of the next best alternative forgone. Rational choice considers this cost explicitly.

Opportunity cost: The value of the next best alternative sacrificed when a decision is made.

For example, if a consumer spends £20 on a book, the opportunity cost might be the meal they could have purchased instead. Incentives and marginal reasoning interact with opportunity cost in shaping rational choices.

Limitations of the Rational Decision-Making Model

While the rational model is a cornerstone of microeconomics, real-world decision making often deviates due to:

Imperfect information: Lack of complete or accurate data.

Bounded rationality: Cognitive and time constraints limit decision quality.

Behavioural biases: Anchoring, overconfidence, and other psychological factors can distort choices.

Nevertheless, understanding rational decision making, incentives, and marginal reasoning is essential for analysing consumer behaviour and market outcomes, as it forms the foundation for more advanced theories in both traditional and behavioural economics.

FAQ

Rational decision making assumes that consumer preferences are complete (every option can be ranked), transitive (if A is preferred to B and B to C, then A is preferred to C), and stable over time.

These assumptions allow economists to model choices consistently and predict behaviour. In reality, preferences can change due to new information, marketing, or social influences, but the theoretical model relies on stability for analytical purposes.

Non-monetary incentives, such as social approval, career progression, or personal fulfilment, can be just as influential as financial rewards.

For example, a worker may choose a lower-paying job for better work-life balance, or a consumer might buy eco-friendly products for environmental reasons despite higher prices. These incentives still fit within rational decision making if they contribute to overall utility maximisation.

Marginal reasoning helps governments decide how to allocate limited resources efficiently.

Policymakers compare the marginal benefit of an additional unit of spending (e.g., on healthcare) with its marginal cost.

Spending continues until the extra benefit from the next pound spent is equal to its opportunity cost.

This approach ensures public funds are directed to areas where they have the greatest impact on welfare.

Time preference refers to how individuals value present consumption compared to future consumption.

A strong preference for present consumption (high time preference) may lead to lower saving and investment.

A low time preference indicates greater willingness to delay consumption for future benefits.

Rational decision making incorporates time preference when evaluating trade-offs between current and future utility, often using discounting methods.

In marginal analysis, opportunity cost measures the value of the best alternative forgone when choosing to consume or produce an additional unit.

By considering opportunity cost, decision makers ensure that resources are shifted only when the gain from the marginal unit outweighs the value lost from the alternative use.

This prevents inefficient allocation, where resources could have been more productive elsewhere.

Practice Questions

Define the term "marginal analysis" and explain its role in rational economic decision making. (2 marks)

1 mark for definition: The comparison of additional benefits and additional costs of a decision to determine the optimal level of an activity.

1 mark for explanation: Used in rational decision making to decide whether to increase or decrease an activity based on whether marginal benefit is greater than, equal to, or less than marginal cost.

Using a diagram, explain how the law of diminishing marginal utility supports the downward-sloping demand curve. (6 marks)

1 mark: Clear diagram showing total utility rising at a decreasing rate or marginal utility declining as quantity consumed increases.

1 mark: Correct labelling of axes and curves (e.g., marginal utility on the vertical axis, quantity on the horizontal axis).

1 mark: Explanation that as consumption increases, the extra satisfaction (marginal utility) from each additional unit decreases.

1 mark: Link between diminishing marginal utility and consumers’ willingness to pay lower prices for additional units.

1 mark: Explanation that the reduction in willingness to pay results in a downward-sloping demand curve.

1 mark: Overall clarity and coherence in connecting the concept to the demand curve.