AQA Specification focus:

‘The proposition that, given certain assumptions, relating for example to a lack of externalities, perfect competition will result in an efficient allocation of resources.’

Introduction

In long-run equilibrium under perfect competition, firms adjust their operations so only normal profit remains, ensuring that resources are allocated efficiently and markets function optimally.

Key Features of Long-Run Equilibrium

Normal Profit

In the long run, firms in perfect competition earn normal profit, meaning revenue just covers opportunity costs. Any short-run abnormal profits attract new firms, driving down prices, while losses cause exit, pushing prices up. This continual adjustment ensures only normal profits persist.

Normal Profit: The minimum profit necessary to keep a firm in business, covering all opportunity costs but not providing excess returns.

This condition signals that resources are neither over- nor under-allocated to the industry.

Entry and Exit Mechanism

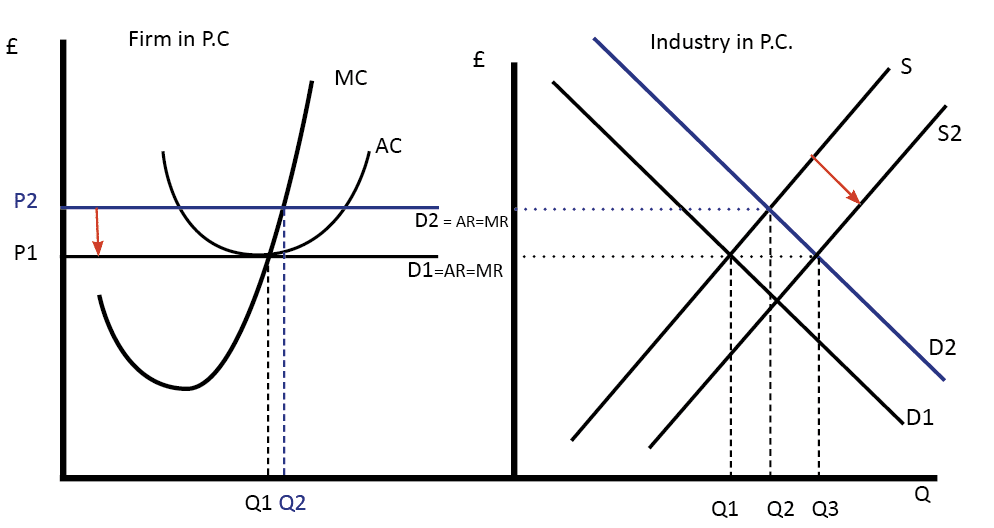

The process of firm entry and exit ensures equilibrium:

Abnormal profit → new firms enter → supply increases → price falls → normal profit restored.

Losses → firms exit → supply decreases → price rises → normal profit restored.

This dynamic process underpins long-run stability.

Efficiency in Long-Run Perfect Competition

Allocative Efficiency

Allocative efficiency occurs when price (P) = marginal cost (MC), meaning resources are used to produce the goods most valued by consumers. At this point, consumer and producer surplus are maximised, with no deadweight loss.

Allocative Efficiency: A situation where resources are allocated to produce the mix of goods and services most desired by society, occurring when P = MC.

This ensures that production reflects consumer preferences.

Productive Efficiency

In long-run equilibrium, firms produce at the minimum point of their average cost curve, meaning no resources are wasted in production.

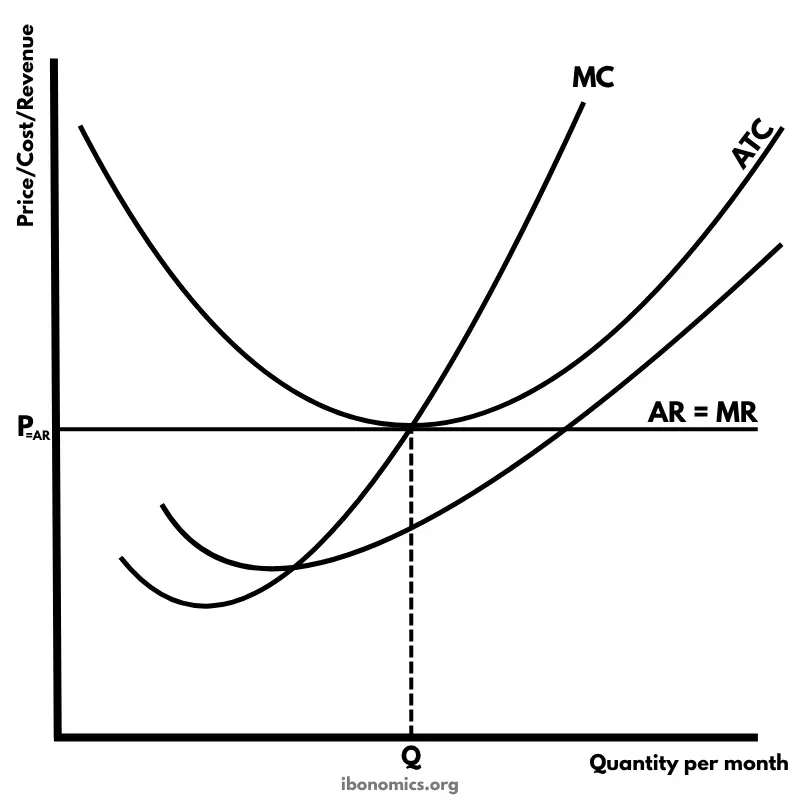

This diagram depicts the long-run equilibrium for a perfectly competitive firm, where the price (P) equals both marginal cost (MC) and average total cost (AC). At this point, the firm earns normal profit, indicating both allocative and productive efficiency. The firm's demand curve is perfectly elastic, reflecting its status as a price taker in the market. Source

Productive Efficiency: Achieved when firms operate at the lowest point of average total cost (AC), minimising the resources required per unit of output.

This ensures firms cannot reduce costs further without altering technology or efficiency levels.

The diagram showcases the long-run equilibrium for a perfectly competitive firm, where the price (P) equals marginal cost (MC) and average total cost (AC). This equilibrium results in normal profit, with the firm operating at the most efficient scale. The perfectly elastic demand curve indicates the firm's price-taking behaviour. Source

Dynamic Efficiency (Assumption-Limited)

While perfect competition promotes static efficiency, it may not strongly encourage dynamic efficiency (innovation, R&D, technological advancement), because long-run normal profits limit available funds for reinvestment. Still, the constant pressure to remain cost-competitive may drive incremental improvements.

Conditions Required for Efficiency

For long-run equilibrium to result in efficient allocation:

Perfect knowledge ensures consumers and producers make informed decisions.

Freedom of entry and exit prevents abnormal profits or losses from persisting.

Homogeneous products guarantee no firm has market power.

Large numbers of buyers and sellers ensure firms are price takers.

No externalities mean private and social costs/benefits align, preventing misallocation of resources.

Any failure of these conditions undermines the efficiency outcome.

Diagrammatic Implications

In the long-run equilibrium:

The firm’s demand curve (perfectly elastic) is tangent to the lowest point of the average cost (AC) curve.

At this point, P = MC = AC, demonstrating both allocative and productive efficiency.

EQUATION

Profit Maximisation Rule: MR = MC

MR = Marginal Revenue, the additional revenue from selling one more unit (£)

MC = Marginal Cost, the additional cost of producing one more unit (£)

Since in perfect competition P = MR, the condition becomes P = MC.

Efficiency Outcomes

Allocative efficiency: Goods produced match consumer demand, as P = MC.

Productive efficiency: Firms produce at the lowest AC, minimising resource use.

Consumer surplus maximised: No price mark-up above cost, so consumers benefit fully.

No deadweight loss: Output is at socially optimal level.

However, dynamic efficiency may be weak, as firms lack monopoly profits to fund innovation.

Benchmark Role of Perfect Competition

Although rarely found in practice, the long-run equilibrium model serves as a benchmark:

It sets a theoretical standard for efficiency.

Real-world deviations from these assumptions highlight inefficiencies in markets such as monopoly or oligopoly.

Policymakers use this benchmark to assess whether intervention is needed to correct market failure.

FAQ

If externalities exist, the efficiency outcomes predicted by perfect competition may not hold. Negative externalities, such as pollution, mean private costs are lower than social costs, leading to overproduction.

Positive externalities, like innovation spillovers, mean private benefits are less than social benefits, causing underproduction. In both cases, the result is misallocation of resources despite the competitive structure.

Supernormal profit attracts new entrants because there are no barriers to entry.

Entry increases market supply.

The increased supply lowers the market price.

Firms are forced to accept this lower price as price takers.

Supernormal profit is eroded until only normal profit remains.

This mechanism works in reverse if firms are making losses, ensuring long-run balance.

Perfect knowledge ensures all participants know prices, costs, and technology.

Consumers can make informed choices about what to buy, while producers cannot hide inefficiencies. Firms quickly adopt best-practice production methods because all cost-saving innovations are shared across the market.

This transparency prevents persistent inefficiency, reinforcing both allocative and productive efficiency in the long run.

Firms in long-run equilibrium earn only normal profit, leaving little financial surplus for research and development.

While competition pushes firms to remain cost-efficient, the absence of monopoly profits reduces incentives for major innovation. The model therefore prioritises static efficiency over dynamic progress, which may limit long-term technological advances in real-world contexts.

In reality, perfect competition rarely exists because assumptions are too strict.

Products are often differentiated, not identical.

Perfect knowledge is impossible.

Barriers to entry usually exist, such as capital requirements.

However, some agricultural markets (e.g. wheat, coffee) approximate the model closely. These real-world examples demonstrate how competitive pressures can still drive prices towards cost, even if true perfect competition is unattainable.

Practice Questions

Explain why firms in a perfectly competitive market earn only normal profit in the long run. (3 marks)

1 mark for identifying that abnormal profit attracts new firms into the market.

1 mark for explaining that entry increases market supply, reducing price until only normal profit remains.

1 mark for mentioning that firms can exit if losses occur, restoring normal profit equilibrium.

Using economic theory, discuss why long-run equilibrium in perfect competition leads to both allocative and productive efficiency. (6 marks)

1 mark for stating that allocative efficiency occurs when P = MC.

1 mark for explaining that this means resources are allocated according to consumer preferences.

1 mark for stating that productive efficiency occurs when firms produce at the lowest point on the AC curve.

1 mark for explaining that this minimises the use of resources per unit of output.

1 mark for recognising that both conditions occur in long-run equilibrium under perfect competition.

1 mark for clear development or example reinforcing why these efficiency outcomes arise (e.g. price-taking behaviour, entry/exit of firms).