AQA Specification focus:

‘The advantages and disadvantages of price discrimination. Students should be aware of real-world examples of price discrimination and be able to assess its impact on producers and consumers.’

Introduction

Price discrimination affects efficiency, welfare, and different stakeholders in significant ways. Its impacts vary depending on market conditions, degree of discrimination, and distributional outcomes.

Understanding Welfare Effects of Price Discrimination

Key Concepts

Price discrimination occurs when a firm charges different prices to different consumers for the same product, not explained by cost differences. It typically requires market power, consumer groups with different price elasticities of demand, and barriers to resale.

There are three recognised degrees of price discrimination:

First-degree (perfect) – each consumer is charged their maximum willingness to pay.

Second-degree – price varies by quantity consumed or version purchased (e.g., bulk discounts, premium versions).

Third-degree – different prices are charged to identifiable groups based on elasticities (e.g., student discounts, peak/off-peak travel).

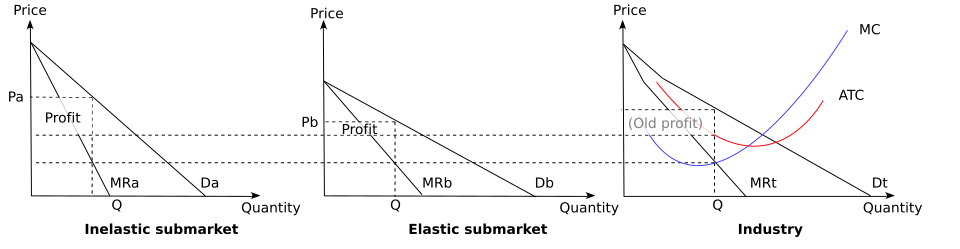

Third-degree price discrimination splits the market into groups with different price elasticities and sets a separate price where MR = MC in each sub-market. The diagram shows total profit rising relative to a single uniform price, illustrating how surplus is reallocated from consumers to the producer. Extra detail included: the graphic labels an “old profit” benchmark to compare outcomes. Source

Welfare Impacts

Effects on Consumers

Consumer surplus: In general, price discrimination reduces consumer surplus as more is captured by producers as profit.

Access to goods/services: Some consumers benefit, as price discrimination can make products affordable to lower-income groups (e.g., discounted rail fares for students).

Equity issues: May worsen inequality if vulnerable consumers are charged higher prices due to inelastic demand (e.g., essential medicines).

Consumer Surplus: The difference between the maximum price a consumer is willing to pay and the price actually paid.

Price discrimination therefore reallocates surplus between consumers and producers depending on the structure of demand.

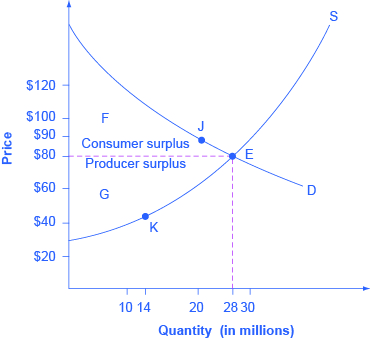

The figure highlights consumer surplus (area above price and below demand) and producer surplus (area below price and above supply) at market equilibrium. It provides a reference for how discrimination can transfer surplus to producers and, when output changes, affect total (social) surplus. Extra detail included: the example uses tablet prices/quantities to illustrate the geometry; these numbers are illustrative rather than required by the syllabus. Source

Effects on Producers

Profitability: Price discrimination allows producers to increase profits by extracting more surplus.

Market coverage: Firms may serve additional customers who would otherwise be excluded at a uniform high price.

R&D and innovation incentives: Higher profits can fund research, product development, and dynamic efficiency.

Stakeholder Impacts

Consumers as Stakeholders

Winners: Price-sensitive consumers (elastic demand) may gain access through lower discriminatory pricing.

Losers: Consumers with inelastic demand often face higher prices, losing welfare.

Producers as Stakeholders

Winners: Firms almost always benefit through higher profits and expanded markets.

Strategic advantage: Ability to segment markets strengthens barriers to entry.

Society and Government

Positive welfare outcomes:

May enhance allocative efficiency by supplying consumers who value the product but could not afford it at a single high price.

Can increase dynamic efficiency through reinvestment of profits.

Negative welfare outcomes:

Potential deadweight loss where output is restricted for some consumers.

Equity concerns if disadvantaged groups are exploited through higher pricing.

Deadweight Loss: The loss of total welfare (consumer and producer surplus) that occurs when market output is below the socially optimal level.

Real-World Examples

Transport Sector

Rail and air travel: Prices vary according to time of booking, journey time, and consumer type (e.g., student or senior discounts).

Welfare impact: Expands access for certain groups while allowing firms to capture profits from inelastic business travellers.

Pharmaceutical Industry

Drug pricing: High-income countries often face higher prices, while lower-income countries may pay less for the same medicine.

Welfare impact: Increases global access but raises fairness questions for consumers paying premium rates.

Digital and Subscription Services

Streaming platforms and software: Different price tiers for basic, premium, and family plans.

Welfare impact: Expands consumer choice but allows firms to capture more surplus.

Evaluation of Welfare Outcomes

Potential Advantages

Improved access: Products made affordable to lower-income or elastic-demand groups.

Higher output: Total production may rise, reducing deadweight loss compared with uniform pricing.

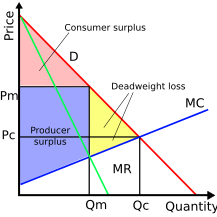

The diagram shows a single-price monopoly setting output below the competitive level, creating deadweight loss (shaded triangle) and reducing total surplus. Use this as the benchmark when explaining how certain forms of price discrimination can expand output and shrink DWL. Extra detail included: the graphic is a general monopoly diagram; price discrimination itself is not depicted. Source

Potential Disadvantages

Consumer exploitation: Inelastic groups may be charged unfairly high prices.

Reduced equity: Distributional concerns if lower-income groups face higher costs for necessities.

Market power abuse: Firms may use discrimination to reinforce dominance and prevent competition.

Key Takeaways for AQA A-Level Economics Students

Price discrimination redistributes welfare between consumers and producers.

The overall welfare impact depends on whether total output rises or falls.

It can lead to dynamic efficiency gains but also risks equity issues and deadweight losses.

Evaluation should weigh producer gains against consumer losses and broader societal welfare implications.

FAQ

Elasticity of demand is central to welfare effects. Groups with more inelastic demand usually face higher prices, losing consumer surplus.

Meanwhile, elastic groups often benefit through lower prices, improving access. The overall welfare outcome depends on the balance of these shifts and whether total output expands.

Price discrimination can either improve or worsen equity.

It improves equity when discounts make products affordable for low-income groups, such as student rail cards.

It reduces equity when essential goods, like medicines, are sold at higher prices to groups with few alternatives.

The net impact on fairness depends on how pricing policies target different consumer segments.

Governments may permit price discrimination in industries like utilities or transport because it helps ensure wider access.

By charging higher prices to those with inelastic demand, firms can cross-subsidise cheaper fares or tariffs for price-sensitive consumers, spreading usage more evenly.

This can support social objectives, such as mobility or energy affordability, even if total consumer surplus declines for some groups.

Allocative efficiency occurs when resources are distributed so that price equals marginal cost.

Price discrimination can move markets closer to this if it leads to greater output, as more consumers who value the good can purchase it at lower prices.

However, if it simply extracts surplus without increasing output, allocative efficiency is not improved and deadweight loss may remain.

Modern technology allows firms to segment markets with far greater precision.

Data tracking enables individualised pricing, sometimes resembling first-degree price discrimination.

This can increase producer surplus significantly while raising concerns about fairness and transparency.

The welfare impact depends on whether output increases or whether it simply redistributes surplus more heavily towards producers.

Practice Questions

Define price discrimination and state one condition necessary for it to occur. (2 marks)

1 mark for an accurate definition: Price discrimination is when a firm charges different prices to different consumers for the same product, not due to cost differences.

1 mark for one correct condition, such as:

The firm must have some degree of market power.

There must be groups of consumers with different price elasticities of demand.

There must be barriers to prevent resale of the product.

Using examples, explain two possible welfare impacts of price discrimination on consumers. (6 marks)

Up to 3 marks for identifying and explaining each valid welfare impact (maximum 2 impacts).

Award 1 mark for identifying a valid point, and up to 2 marks for development/explanation with reference to welfare.

Possible points:

Consumer surplus loss (1 mark): Price discrimination allows firms to capture more surplus as profit. Further development (1–2 marks): Inelastic demand consumers may face higher prices, reducing welfare.

Improved access (1 mark): Some consumers may benefit from lower discriminatory pricing. Further development (1–2 marks): For example, student discounts allow lower-income groups to consume products otherwise unaffordable, increasing their welfare.

Examples must be relevant (e.g., rail travel discounts, pharmaceutical pricing). Award up to 1 additional mark per point for clear, well-chosen examples that link back to welfare.

Maximum 6 marks in total.