AQA Specification focus:

‘The economic consequences of such policies.’

Government policies aimed at redistributing income and wealth have significant economic consequences. They influence efficiency, incentives, and long-term growth, shaping both individual behaviour and macroeconomic performance.

Efficiency and Redistribution

Efficiency in economics refers to the optimal allocation of scarce resources to maximise output and welfare. Redistribution policies can either enhance or reduce efficiency depending on design.

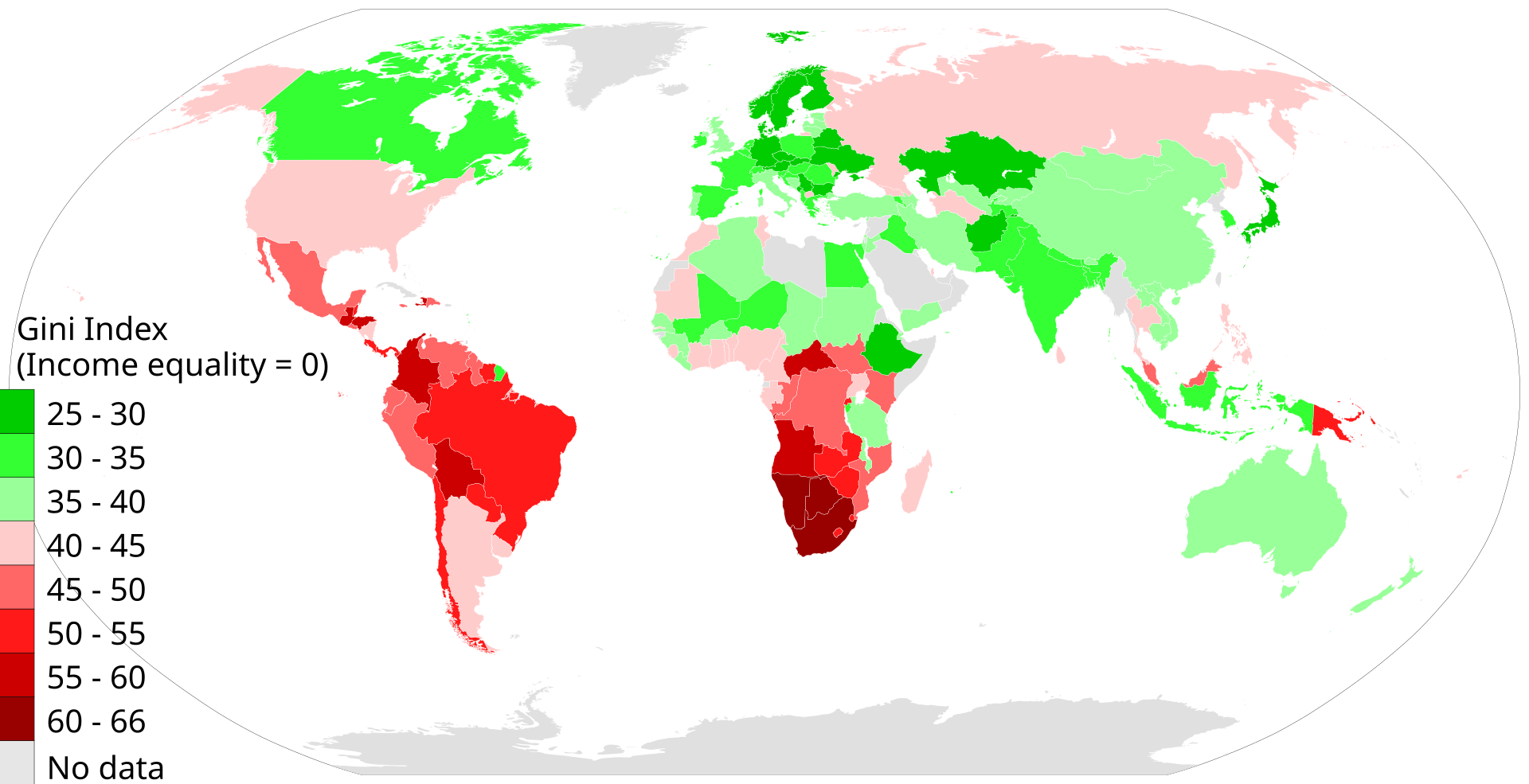

This map illustrates the Gini Index scores by country, indicating levels of income inequality worldwide. Countries with higher Gini scores experience greater income disparity, which can influence the design and effectiveness of redistribution policies. Note that the data reflects 2014 figures, and more recent information may be available. Source

Potential Efficiency Gains

Correcting market failures: Redistribution may improve resource allocation where markets fail, such as when poverty restricts access to education and healthcare, limiting productivity.

Public goods and merit goods: Funding through taxation can ensure wider access to goods like education, healthcare, and infrastructure, improving long-term economic efficiency.

Reducing under-consumption: Transfer payments and welfare benefits increase demand from low-income households, addressing demand deficiency and stabilising the economy.

Efficiency Costs

Deadweight losses from taxation: Taxes may distort decision-making, such as discouraging investment or reducing labour supply.

Misallocation of resources: Subsidies or transfers can sometimes lead to inefficiency if not well-targeted, creating dependency rather than supporting productivity.

Government failure: Poorly designed redistribution may result in waste, administrative inefficiency, or unintended outcomes.

Incentives and Behavioural Effects

Redistribution policies significantly affect incentives for individuals and firms. Incentives influence decisions to work, save, invest, and innovate.

Labour Market Incentives

Income tax effects: High marginal tax rates may discourage additional work effort (substitution effect) but can also create an income effect where individuals work harder to maintain after-tax earnings.

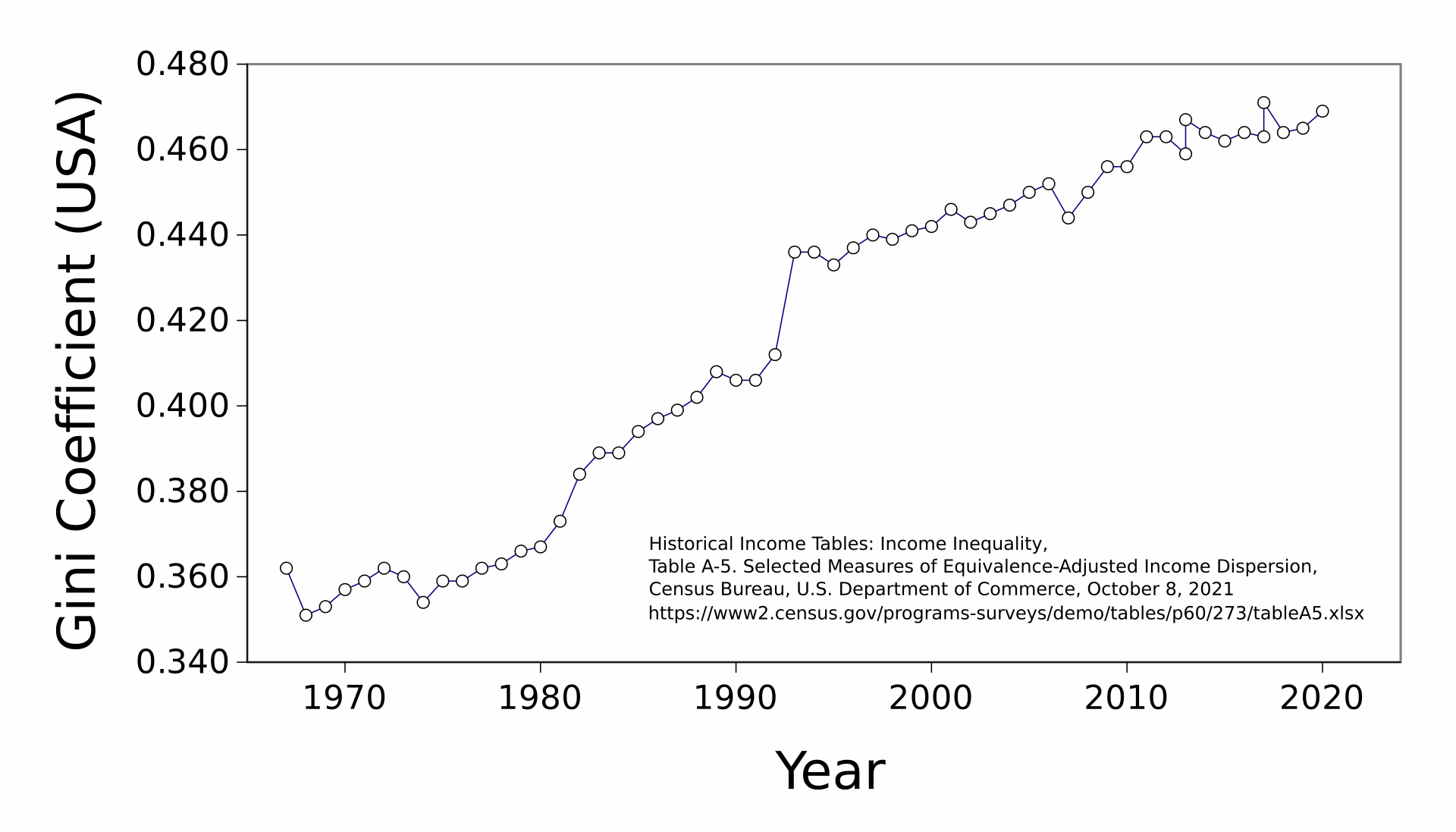

This line graph depicts the Gini coefficient for the United States from 1967 to 2020, highlighting periods of increasing and decreasing income inequality. The data can be used to analyse how changes in tax policy and welfare programs have influenced income distribution and individual incentives over time. Source

Welfare benefits: Generous welfare systems may reduce the incentive to seek employment if benefits are comparable to low-wage work.

Poverty Trap: A situation where individuals have little financial incentive to increase earnings because additional income results in high effective marginal tax rates through benefit withdrawal.

Saving and Investment Incentives

Capital taxation: High taxes on dividends, capital gains, or inheritance may discourage long-term savings and entrepreneurship.

Redistribution via subsidies: Incentives for investment in education, training, or renewable energy can encourage productive behaviour that enhances growth.

Corporate Incentives

Profit taxation: Excessive corporate tax may reduce investment and innovation, while targeted tax relief can stimulate research and development.

Regulation effects: Redistribution through regulation (e.g., minimum wage laws) alters firm incentives to hire or automate.

Growth Implications

Redistribution influences both short-term aggregate demand and long-term supply-side growth. The overall impact depends on balancing incentives with equity.

Positive Growth Effects

Human capital accumulation: Redistribution that funds education, skills, and health boosts labour productivity, enhancing long-term growth potential.

Demand-side stabilisation: Transfers to low-income groups raise consumption, supporting aggregate demand and reducing recessionary risks.

Social stability: Reducing inequality can prevent social unrest, creating an environment conducive to sustainable growth.

Negative Growth Effects

Reduced entrepreneurial activity: High taxes on profits and wealth may discourage innovation, risk-taking, and capital accumulation.

Capital flight: In a globalised economy, mobile capital may relocate to lower-tax jurisdictions, reducing domestic investment.

Lower labour participation: If welfare systems significantly reduce work incentives, the economy may suffer from lower output.

Balancing Efficiency, Incentives, and Growth

Redistribution involves trade-offs between fairness and economic performance. Economists debate whether redistribution enhances or restricts efficiency, incentives, and growth.

Efficiency–Equity Trade-off

Some argue that redistribution sacrifices efficiency to achieve fairness.

Others highlight that inequality itself can be inefficient by restricting opportunities and weakening demand.

Equity–Efficiency Trade-off: The conflict between ensuring a fair distribution of resources (equity) and maximising total economic output (efficiency).

Policy Design Considerations

Progressive taxation vs. flat taxation: Progressivity can reduce inequality but risks discouraging effort at higher income levels.

Universal benefits vs. means-tested benefits: Universal benefits avoid disincentives but are costly; means-testing targets resources efficiently but may create poverty traps.

Dynamic vs. static effects: Policies must consider long-term behavioural adjustments, not just immediate redistribution outcomes.

Economic Perspectives on Redistribution

Different schools of thought provide contrasting views on how redistribution affects efficiency, incentives, and growth.

Keynesian Perspective

Supports redistribution to stimulate demand and prevent under-consumption.

Emphasises short-term aggregate demand management to maintain full employment.

Classical and Neoclassical Perspectives

Concerned with distortions caused by taxation and welfare.

Stress that incentives for work and investment are key drivers of long-term growth.

Modern Approaches

Behavioural economics: Recognises that responses to incentives may not always be rational, suggesting carefully designed policies can influence behaviour positively.

Inclusive growth models: Argue that redistribution supporting human capital and reducing inequality enhances sustainable long-term growth.

By understanding the economic consequences of redistribution through the lenses of efficiency, incentives, and growth, students can evaluate policies critically and appreciate their broader implications for society and the economy.

FAQ

Redistribution can raise productivity by funding education, healthcare, and training, which enhance human capital. A healthier, more skilled workforce boosts efficiency in production.

However, if redistribution reduces work incentives or diverts resources into inefficient programmes, productivity growth may slow. The overall impact depends on policy design and targeting.

Redistribution increases the disposable income of lower-income households, who have a higher marginal propensity to consume. This strengthens aggregate demand and reduces risks of under-consumption.

In downturns, such spending helps cushion recessions, while in expansions, it can sustain balanced growth without overreliance on wealthier groups’ spending.

High taxation on wealth, dividends, or profits can encourage investors to move capital abroad to lower-tax countries. This reduces domestic investment and government revenue.

Globalisation increases this risk, as financial markets are mobile and businesses can relocate operations. Effective international coordination or targeted incentives can help limit capital flight.

Redistribution may improve fairness (equity) but reduce efficiency if it distorts incentives for work, saving, and investment.

Some argue the trade-off is overstated, since extreme inequality can itself be inefficient by restricting opportunities and weakening long-term demand.

Behavioural economics recognises that individuals may not always respond rationally to incentives. For example, welfare recipients may undervalue long-term benefits of work.

Policies can use “nudges” such as automatic enrolment in training or savings schemes, encouraging positive behaviour without heavy financial penalties. This can make redistribution more effective.

Practice Questions

Define the term poverty trap and explain briefly how it relates to incentives in the labour market. (2 marks)

1 mark for a correct definition of poverty trap: where individuals have little financial incentive to increase earnings because additional income is offset by benefit withdrawal or higher taxes.

1 mark for linking the concept to labour market incentives, e.g., reduced motivation to seek higher-paid work due to minimal net gain in income.

Discuss the potential effects of redistribution policies on economic growth, considering both positive and negative impacts. (6 marks)

Up to 2 marks for identifying and explaining positive growth effects (e.g., improved human capital through education and healthcare, increased aggregate demand, social stability).

Up to 2 marks for identifying and explaining negative growth effects (e.g., reduced entrepreneurial activity, capital flight, reduced labour participation).

Up to 2 marks for evaluation or balance (e.g., noting the trade-off between equity and efficiency, arguing that long-term benefits may outweigh short-term costs, or recognising that outcomes depend on policy design).