AQA Specification focus:

‘Why the absence of property rights leads to externalities in both production and consumption and hence market failure.’

The absence of clearly defined property rights often results in externalities, where private decision-making ignores wider social costs and benefits, leading to resource misallocation and market failure.

Understanding Property Rights

Property rights refer to the legal ownership and control over a resource, asset, or good. When rights are well-defined and enforced, the owner has both the ability and incentive to use, maintain, or transfer the resource efficiently.

Property Rights: The legal entitlement to own, use, and transfer a resource, including the responsibility for the consequences of its use.

Without clear rights, no individual or organisation has a direct incentive to protect or efficiently allocate the resource, creating opportunities for overuse or under-provision.

Externalities and the Link to Property Rights

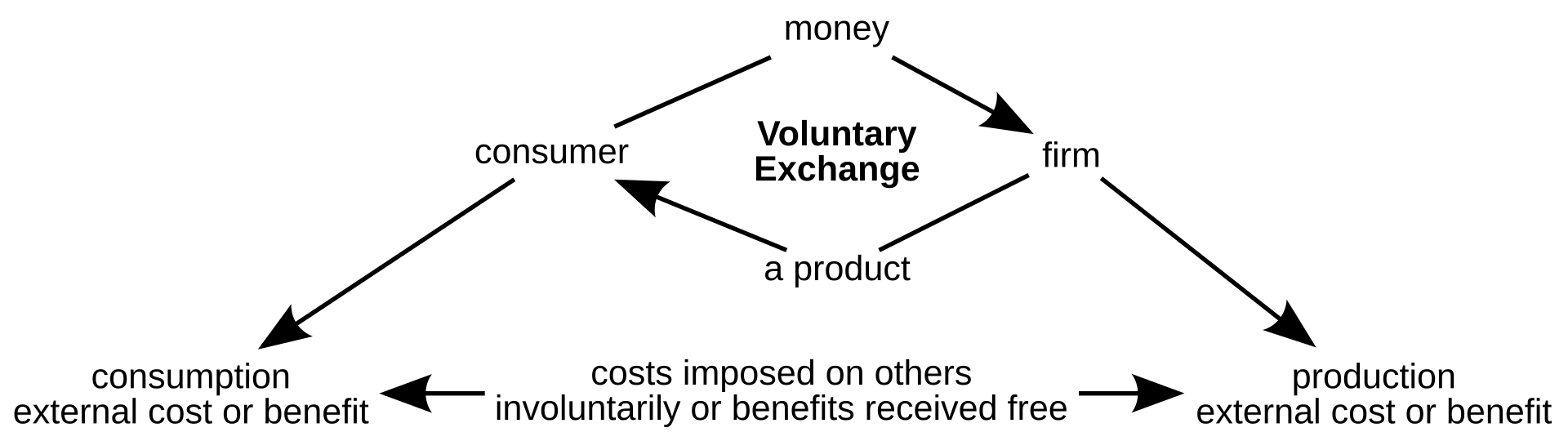

Externalities arise when the production or consumption of goods and services imposes costs or benefits on third parties not reflected in the market price.

Externality: A cost or benefit from economic activity that affects third parties not directly involved in the transaction, and which is not accounted for by the market price.

The absence of property rights often explains why such externalities exist, since nobody bears full responsibility for the effects of their actions on others.

Negative Externalities

Occur when activities impose costs on third parties.

Examples include pollution, deforestation, and traffic congestion.

Lack of property rights means polluters are not charged for damage caused, leading to over-production.

Positive Externalities

Occur when activities create benefits for third parties.

Examples include vaccinations or education.

Without rights to capture these benefits, producers under-invest, leading to under-production.

The Problem of Common Resources

Common resources are natural or social resources accessible to all, such as air, oceans, and public parks. These lack clear ownership, leading to misuse.

Common Resource: A resource that is non-excludable (difficult to prevent access) but rivalrous (its use by one reduces availability for others).

Without property rights, these resources are prone to over-exploitation. The classic issue is the ‘tragedy of the commons’, where self-interest drives unsustainable consumption.

NOAA trawl-survey operations illustrate harvesting from a shared fishery—a common-pool resource. Where property rights are ill-defined or unenforced, individual incentives can push aggregate effort beyond the social optimum. This photo includes operational survey details that exceed the syllabus, but it remains a precise real-world context for the concept. Source

Production Externalities and Property Rights

In production, absent or weak property rights can cause significant inefficiencies:

Factories and pollution: Firms may dump waste into rivers without restriction, since no one holds enforceable rights over the water.

Overfishing: Without ownership of fishing waters, each fisherman over-exploits stocks, leading to depletion.

Deforestation: If land rights are unclear, loggers exploit forests without considering long-term costs.

In each case, the lack of rights prevents costs being internalised, causing a divergence between private cost and social cost.

A schematic of an externality: a producer–consumer transaction generates a spillover that affects a third party without compensation. Assigning or enforcing property rights (or pricing the spillover) is one route to internalise this effect. The diagram is generic by design, which aligns with the conceptual focus of this subsubtopic. Source

Consumption Externalities and Property Rights

Consumption activities are also affected by unclear property rights:

Noise pollution: Without enforceable rights to quiet, households endure disruptions without compensation.

Smoking in public: No rights to clean air in shared spaces means non-smokers bear health costs.

Urban congestion: Lack of rights to road use results in overcrowding, delays, and higher fuel costs for all users.

These outcomes highlight how weak rights reduce efficiency and welfare in consumption decisions.

The Role of Enforceability

Even when rights are defined, their effectiveness depends on enforceability. For example, laws against industrial pollution may exist, but weak enforcement results in continued negative externalities. Strong enforcement ensures that property rights act as a mechanism to internalise costs and benefits.

Internalising Externalities with Property Rights

When rights are assigned and enforced, externalities can be reduced through market negotiation. This principle is outlined in the Coase Theorem.

Coase Theorem: The idea that if property rights are well-defined and transaction costs are low, parties can negotiate to internalise externalities and achieve an efficient allocation of resources.

For instance, if residents hold rights to clean air, they can demand compensation from polluters, incentivising firms to reduce emissions. Conversely, if firms have rights, residents may pay them to cut pollution.

Challenges in Applying Property Rights

While property rights are crucial, there are limitations to their effectiveness:

High transaction costs: Negotiations may be impractical when many parties are involved.

Information asymmetry: Parties may not know the true extent of costs or benefits.

Non-excludability: Some resources, like the atmosphere, are inherently difficult to assign rights to.

Equity concerns: Assigning rights may create fairness issues, as those with wealth may dominate negotiations.

Key Points for AQA A-Level Students

Absence of property rights explains why externalities persist in both production and consumption.

This leads to market failure, since markets misallocate resources when costs and benefits are not fully internalised.

Effective rights and enforcement can reduce or eliminate inefficiencies, though practical challenges often remain.

FAQ

Clear property rights assign responsibility for the use and preservation of resources. Owners have an incentive to maintain long-term value, reducing unsustainable exploitation.

For example, when fisheries are privately managed, quotas can prevent overfishing. Similarly, landowners are more likely to invest in soil conservation if they hold secure rights.

Even if property rights exist, high transaction costs can stop parties from negotiating efficient solutions.

Costs may arise from:

Legal fees or contracts

Monitoring and enforcement

Coordination between large numbers of affected parties

This makes internalisation less practical in real-world markets.

Assigning rights to fully non-excludable goods such as clean air is extremely difficult.

Governments sometimes use indirect methods, such as pollution permits or carbon pricing, which simulate property rights over emissions. These systems help approximate control where direct assignment is not feasible.

Allocating rights can raise fairness concerns. Wealthy groups may dominate negotiations, capturing benefits at the expense of poorer groups.

This is especially significant in developing economies, where unclear rights often affect land and natural resources. Equity concerns can therefore complicate efficient solutions.

Even when rights exist on paper, weak enforcement undermines their value.

For instance:

Polluters may ignore fines if enforcement is lax

Illegal logging continues where property rights are unenforced

Corruption can erode trust in ownership systems

Enforcement quality is as important as defining rights themselves.

Practice Questions

Define the term property rights and explain why their absence can lead to market failure. (2 marks)

1 mark for a correct definition of property rights: the legal entitlement to own, use and transfer a resource, including responsibility for its use.

1 mark for explaining the link to market failure, e.g. absence of rights leads to overuse, externalities, or misallocation of resources.

Using examples, explain how the absence of property rights can cause negative externalities in production and consumption. (6 marks)

1–2 marks: Identification of negative externalities in production (e.g. pollution, overfishing) or consumption (e.g. smoking, noise).

1–2 marks: Explanation of why absence of property rights prevents costs being internalised, leading to divergence between private and social costs.

1–2 marks: Use of relevant examples to support the explanation (e.g. factories dumping waste in rivers, smokers imposing health costs on others).

Maximum 6 marks for a well-structured explanation that covers both production and consumption with examples and clear economic reasoning.