IB Syllabus focus:

‘Everyone has the right to a pollution-free environment and fair resource access. Inequalities (income, race, gender, culture) drive disparities in water, food, and energy, seen in local and global cases.’

Environmental justice addresses fairness in how environmental benefits and burdens are shared. It links to inequalities where race, gender, culture, or wealth influence access to resources and exposure to risks.

Understanding Environmental Justice

Environmental justice is rooted in the idea that all people, regardless of background, deserve equal access to a clean, safe environment. It recognises that pollution, resource shortages, and environmental hazards often impact disadvantaged communities more severely.

Environmental Justice: The principle that everyone has the right to equal protection from environmental harm and equal access to environmental benefits.

This principle emphasises that environmental policies, decisions, and resource distributions should be applied fairly, without discrimination or bias.

Causes of Environmental Inequalities

Environmental inequalities stem from multiple overlapping factors. These inequalities are not only local but also visible on global scales.

Key Drivers of Inequality

Income: Wealthier individuals and nations can afford cleaner energy, safe water, and effective waste management, while poorer communities face greater pollution risks.

Race and Ethnicity: Minority groups are often more likely to live near hazardous waste sites or polluting industries.

Gender: Women, particularly in developing countries, may face higher risks due to responsibilities for water collection, fuel use, and caregiving.

Culture: Indigenous and traditional communities often depend directly on natural resources, making them vulnerable when ecosystems are degraded or access is restricted.

These drivers intersect, intensifying the scale and severity of inequality.

Resource Access and Distribution

Environmental justice is closely tied to access to resources, including water, food, and energy.

Water: In many regions, unequal water distribution means some communities suffer from scarcity while others have reliable access.

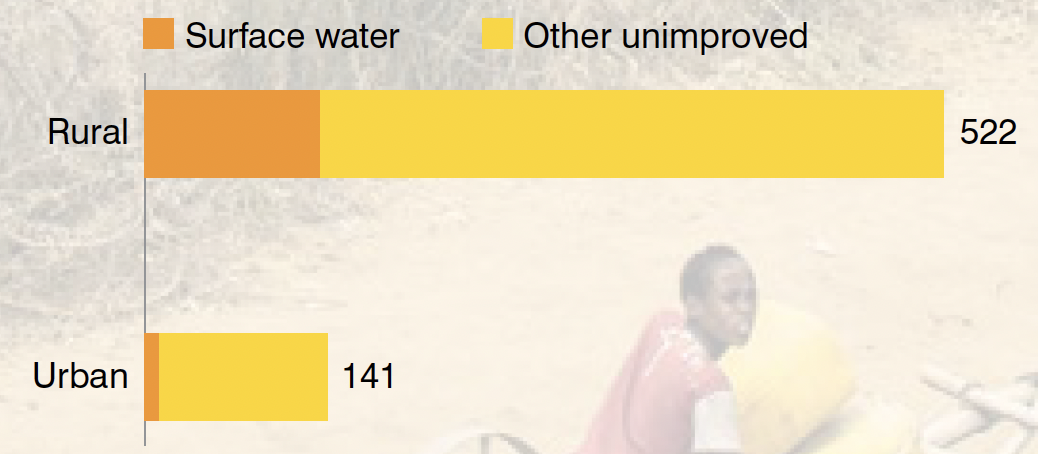

Bar chart comparing rural vs urban populations using unimproved drinking-water sources (2015), demonstrating that rural communities bear the heaviest burden. The visual reinforces how access inequalities translate into health and environmental risks. Source.

Food: Food insecurity often arises where resources are unequally distributed, leading to malnutrition in poorer areas.

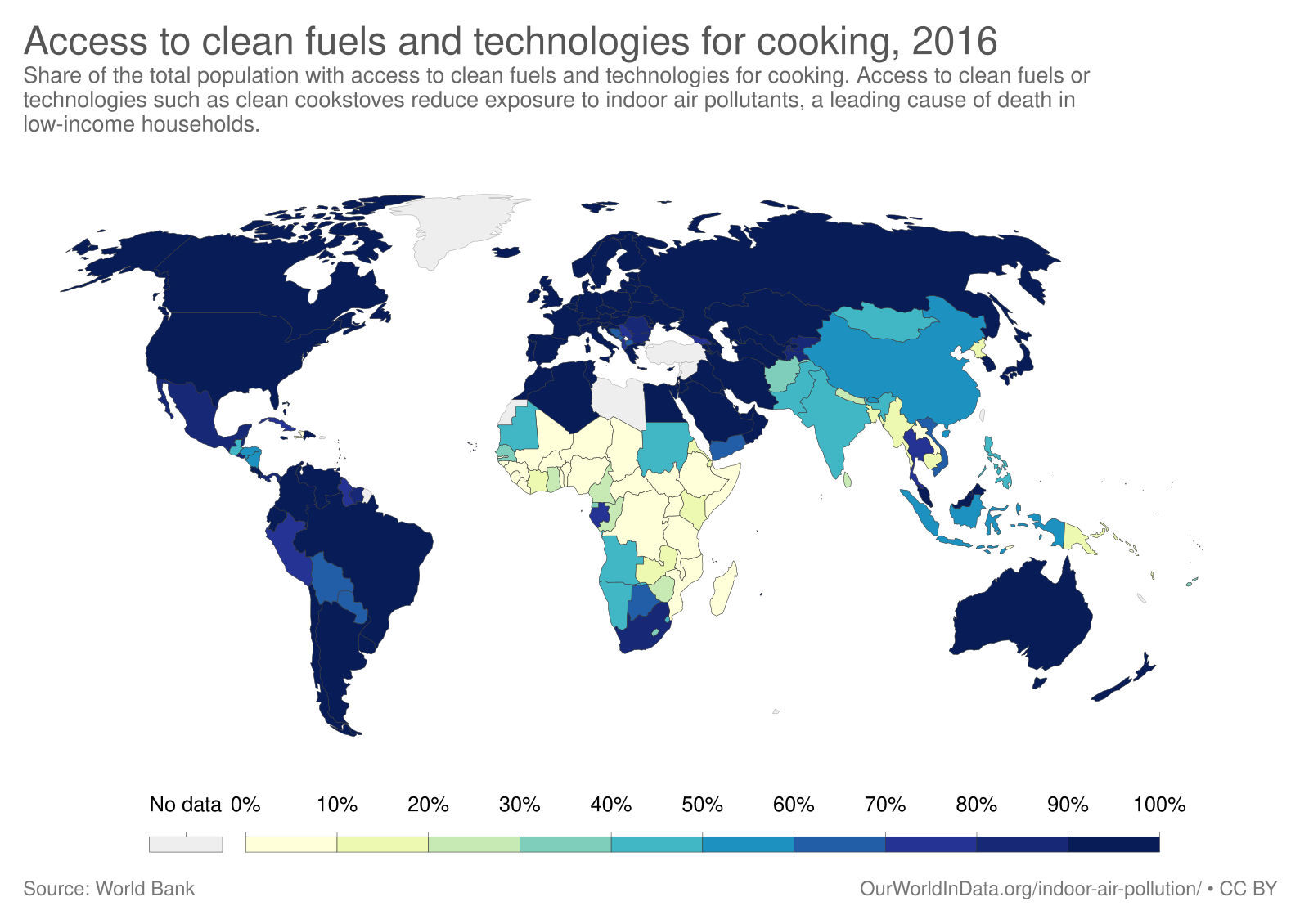

Energy: Access to clean energy technologies is often limited in developing nations, increasing reliance on polluting sources like biomass or coal.

World map showing the share of each country’s population with access to clean fuels and technologies for cooking, highlighting stark regional disparities linked to health and social inequality. This supports discussions of energy poverty and its role in environmental justice. Source.

Resource Inequality: Unequal distribution of essential resources, such as food, water, and energy, leading to disparities in quality of life and environmental security.

Resource inequality frequently reinforces cycles of poverty and environmental degradation, as communities lacking resources may resort to unsustainable practices.

Local Cases of Environmental Justice

Localised examples highlight how inequalities manifest within nations.

Examples

Low-income urban neighbourhoods exposed to air pollution from traffic and industry.

Communities near toxic waste sites or landfills, where land values are low and residents have limited political influence.

Unequal access to green spaces, which reduces opportunities for recreation and health benefits.

These cases show how socioeconomic status often determines exposure to environmental hazards.

Global Cases of Environmental Justice

Globally, inequalities extend across borders, shaping international environmental challenges.

Examples

Developing countries disproportionately suffer the effects of climate change despite contributing the least to greenhouse gas emissions.

Export of hazardous waste from wealthy nations to poorer countries with weaker environmental regulations.

High-resolution photograph of the Agbogbloshie e-waste site in Accra, Ghana, showing informal processing and visible smoke from burning scrap—an example of transboundary waste burdens on vulnerable communities. The photo adds context on livelihoods at the site (extra detail not required by the syllabus, included here for clarity). Source.

Large-scale resource exploitation, such as mining and deforestation, often benefits global markets while harming local communities.

Such disparities highlight how global systems of trade, economics, and governance perpetuate environmental injustice.

Links to Social and Environmental Policy

Addressing environmental justice requires integration into policies at all scales.

Policy Approaches

International agreements: Aim to ensure equitable climate action, such as the Paris Agreement.

National legislation: Can regulate pollution, protect vulnerable groups, and enforce fair distribution of resources.

Local activism: Grassroots campaigns often push for recognition of community rights and environmental protection.

Effective policies must recognise the intersection of environmental and social issues, ensuring that environmental benefits and protections reach all groups fairly.

Environmental Justice and Human Rights

The concept of environmental justice is strongly tied to human rights.

Right to a Pollution-Free Environment: The belief that every person has the fundamental right to live in a healthy environment without exposure to harmful levels of pollution.

This right frames environmental issues as ethical and legal concerns, demanding accountability from governments and corporations.

Environmental Inequalities and Sustainable Development

Environmental inequalities directly challenge the goals of sustainability. When access to clean water, food, or energy is unequal, long-term resilience and stability are undermined.

Connections to Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)

Goal 6: Ensure availability and sustainable management of water and sanitation for all.

Goal 7: Ensure access to affordable, reliable, sustainable, and modern energy.

Goal 10: Reduce inequality within and among countries.

Goal 13: Take urgent action to combat climate change and its impacts.

These goals place environmental justice at the heart of sustainable global progress.

The Role of Social Movements

Social movements play a central role in promoting environmental justice.

Community-led protests against polluting industries.

Campaigns highlighting environmental racism, where specific ethnic groups disproportionately bear environmental burdens.

Advocacy for climate justice, linking human rights and fairness to climate policies.

These movements demonstrate that change often comes from collective action rather than top-down initiatives.

FAQ

Environmental justice focuses on ensuring fair treatment and meaningful involvement in environmental decision-making, addressing both outcomes and participation.

Environmental equity refers mainly to the fair distribution of environmental benefits and burdens, without necessarily considering the decision-making process.

Justice goes beyond equity by recognising power imbalances, historical disadvantages, and the right of affected communities to have a voice.

Environmental racism is when racial or ethnic groups are disproportionately exposed to environmental hazards, such as living near polluting industries or waste dumps.

Environmental justice addresses this issue by advocating for equal protection regardless of race and ensuring vulnerable groups are not unfairly burdened.

This concept highlights the intersection of social inequality and environmental harm.

Clean energy access reduces reliance on polluting fuels like coal or biomass, which often harm poorer households through indoor air pollution.

Communities lacking modern energy remain disadvantaged in health, education, and economic development.

Environmental justice recognises that access to clean energy is not just a technological challenge but also a matter of fairness and rights.

Wealthier nations often export hazardous waste to poorer countries with weaker environmental safeguards.

This creates injustice because:

Local communities face health risks from toxic exposure.

Environmental damage undermines livelihoods and ecosystems.

Benefits of production are enjoyed elsewhere, while costs are externalised.

Environmental justice seeks to address this imbalance through stricter international regulation.

Grassroots movements amplify community voices in decision-making and highlight injustices that might otherwise be ignored.

They often mobilise around specific issues such as:

Local air and water pollution.

Access to safe drinking water.

Opposition to hazardous facilities.

By pressuring governments and corporations, these movements can achieve policy changes and greater accountability.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (2 marks)

Define environmental justice and explain why it is important in addressing inequalities.

Mark Scheme:

1 mark for a correct definition of environmental justice (e.g., the fair distribution of environmental benefits and burdens among all people).

1 mark for linking importance to addressing inequalities (e.g., ensuring equal access to resources, protecting vulnerable communities from disproportionate environmental harm).

Question 2 (5 marks)

Discuss how income and culture influence inequalities in access to water, food, or energy. Provide at least one local and one global example.

Mark Scheme:

1 mark for describing income as a driver (e.g., wealthier groups/nations can afford clean water, food security, renewable energy).

1 mark for describing culture as a driver (e.g., Indigenous or traditional groups often more vulnerable due to reliance on ecosystems).

1 mark for explaining a local example (e.g., poorer urban neighbourhoods exposed to unsafe water or limited food access).

1 mark for explaining a global example (e.g., developing countries contributing least to climate change but facing the greatest energy/water challenges).

1 mark for explicitly linking both factors to inequalities in environmental justice.