OCR Specification focus:

‘Define optical isomerism as non-superimposable mirror images about a chiral centre; identify chiral carbons.’

Optical isomerism arises when molecules contain chiral centres, producing non-superimposable mirror images. Understanding chirality is essential for predicting stereochemical behaviour and recognising isomers in organic structures.

Optical Isomerism in Organic Molecules

Optical isomerism is a form of stereoisomerism in which molecules share the same structural formula but differ in the spatial arrangement of atoms around a key feature. According to the specification, optical isomerism occurs when molecules exist as non-superimposable mirror images due to the presence of a chiral centre. This phenomenon is particularly significant in biological and synthetic chemistry, where different spatial arrangements of atoms can result in dramatically different behaviours.

The Chiral Centre

A chiral centre is the structural feature that allows optical isomers to exist.

Chiral Centre: A carbon atom attached to four different groups, producing non-superimposable mirror-image isomers.

Recognising a chiral centre is essential for identifying when optical isomerism will occur in a molecule. Not every carbon in an organic molecule is chiral: only those bonded to four distinct substituents meet the requirement. Many naturally occurring molecules, including amino acids and sugars, contain one or more chiral centres, contributing to their three-dimensional complexity.

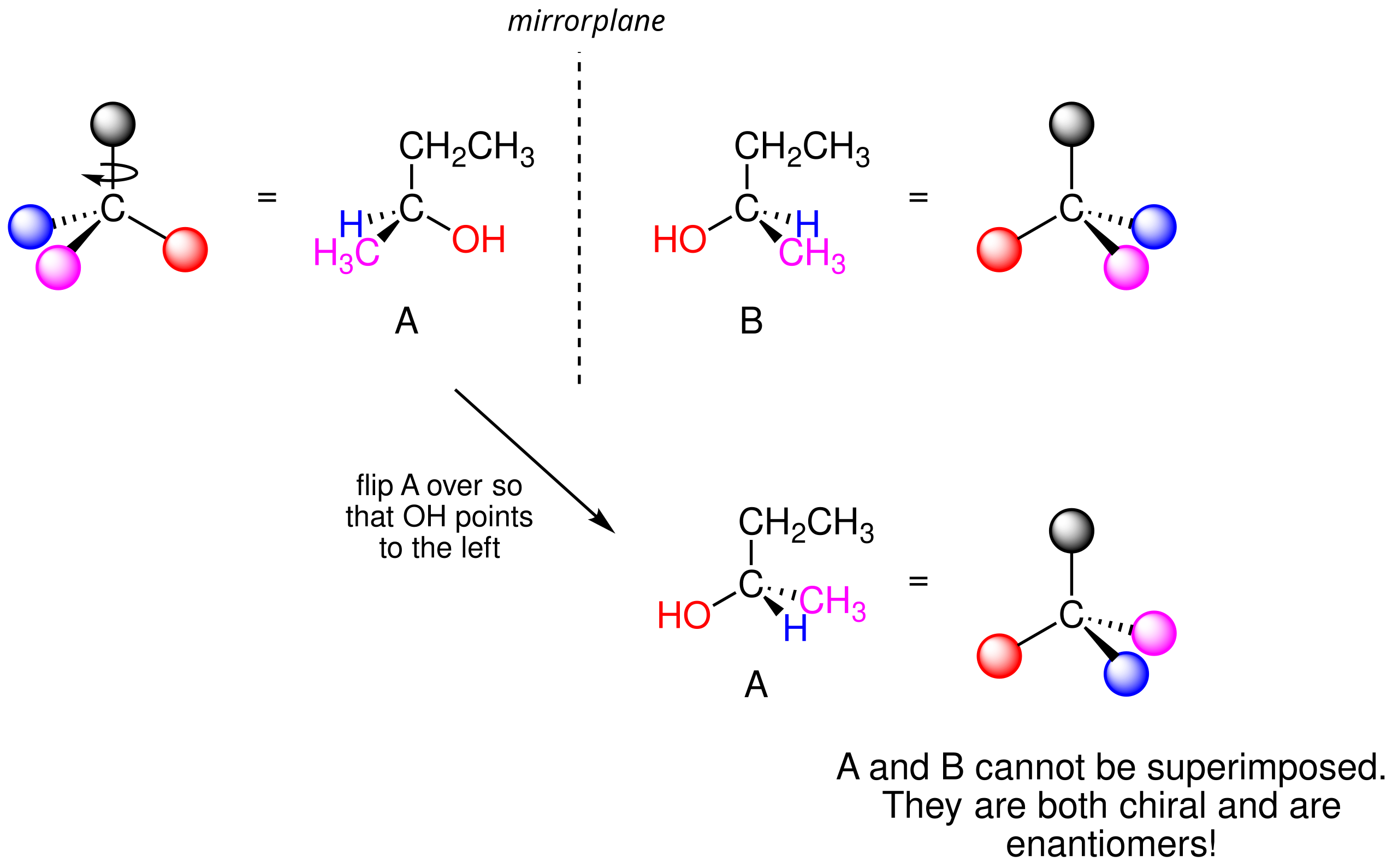

A molecule with a single chiral centre typically forms two stereoisomers, known as enantiomers. These enantiomers are related as right and left hands: they appear as mirror images yet do not align when superimposed.

This diagram shows 2-butanol and its mirror image separated by a mirror plane. Even after rotation, the two structures cannot be perfectly overlaid, demonstrating non-superimposable mirror images (enantiomers). Source

Properties of Enantiomers

Enantiomers share almost all physical properties, such as boiling point and density, but differ in how they interact with plane-polarised light and other chiral environments.

Key characteristics of enantiomers include:

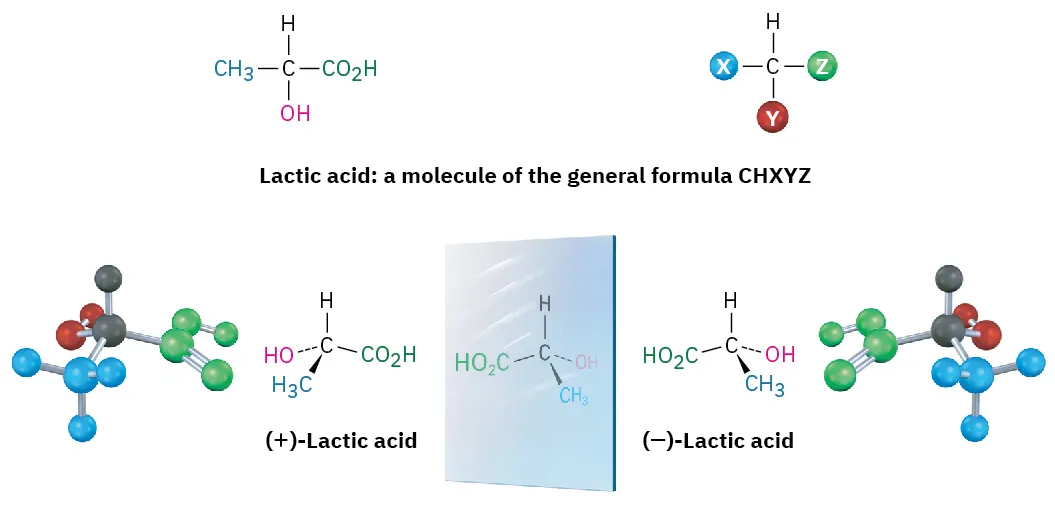

Optical activity: one enantiomer rotates plane-polarised light clockwise (d- or +-isomer), while the other rotates it anticlockwise (l- or –-isomer).

Identical chemical properties in achiral environments but potentially different reactions in chiral biological systems.

Non-superimposable mirror-image relationship, which is required by the specification.

Although rotation of plane-polarised light is an important property of enantiomers, OCR expects students to focus on identifying when molecules show optical isomerism by locating their chiral centres and recognising mirror-image relationships.

Identifying Optical Isomerism in Structures

Correct identification of chirality requires careful inspection of the substituents attached to carbon atoms.

To recognise a chiral centre:

Check that the carbon forms four single covalent bonds.

Confirm all four attached groups differ.

Rotate the molecule mentally or on paper to ensure that no two groups are identical in three-dimensional arrangement.

Avoid being misled by rearranged or redrawn structures that appear to contain duplicates but do not.

Features that prevent chirality include:

A carbon bonded to two identical groups.

Double or triple bonds (which remove the possibility of four distinct substituents).

Molecular symmetry that cancels the potential for non-superimposable mirror images.

Representing Optical Isomers

To communicate optical isomerism effectively, chemists use structural conventions that highlight three-dimensional arrangement.

Important representation methods include:

Wedge–dash notation, where solid wedges project out of the plane, dashed wedges project behind, and straight lines lie within the plane.

Mirror-image diagrams, showing the left-hand and right-hand enantiomers side by side.

Fischer projections, most common with biomolecules, where horizontal lines represent bonds coming out of the plane.

These representations help illustrate the differences between enantiomers, even when they share identical molecular formulas.

Chirality in Amino Acids

Amino acids, particularly α-amino acids, often feature chirality due to the carbon atom bonded to an amine group, a carboxylic acid group, a hydrogen atom, and a variable side chain. This arrangement produces one chiral centre in most cases, in line with the specification requirement to identify chiral carbons.

This figure links the general chiral carbon idea (CHXYZ) to lactic acid, where the central carbon is bonded to four different groups. The mirror-image pair represents enantiomers; the (+)/(–) labels indicate optical rotation, which extends slightly beyond the basic identification requirement. Source

Key points for α-amino acids:

The α-carbon is usually chiral, with glycine being the exception because it contains two hydrogen atoms attached to the central carbon.

Natural amino acids in proteins are overwhelmingly of the L-configuration, reflecting biological preference.

Strategies for Determining Chirality

When evaluating unfamiliar structures:

Identify all tetrahedral carbons.

Check each candidate carbon for four different attached groups.

Examine long or branching substituents carefully, ensuring they truly differ.

Look for internal planes of symmetry, which may eliminate chirality even when a carbon initially appears to satisfy the requirements.

Students should practise scanning structures methodically, as diagrams in examination questions may vary in orientation and complexity.

Multiple Chiral Centres

Some molecules contain more than one chiral centre, increasing the number of possible stereoisomers. This subsubtopic does not require detailed enumeration of stereoisomers but recognising that molecules with multiple chiral centres display greater stereochemical complexity is valuable for synthesis and interpretation.

Examples of molecules commonly examined for multiple chiral centres include:

Carbohydrates such as glucose.

Certain pharmaceuticals with multiple asymmetric carbons.

Complex natural products.

Understanding how each chiral centre contributes to the overall stereochemical identity helps in navigation of multi-functional structures.

Importance of Identifying Chiral Carbons

OCR emphasises the skill of identifying chiral carbons because it enables students to:

Determine when optical isomerism is possible.

Interpret stereochemical notation in synthetic pathways.

Predict structural relationships in biologically relevant molecules.

Connect chirality to functional group behaviour in wider organic contexts.

Chirality plays a major role in synthesis, pharmacology, and biochemistry. Correctly recognising optical isomerism ensures accurate interpretation of molecular structures throughout A-Level Organic Chemistry.

FAQ

Molecular symmetry can prevent optical activity even if a carbon appears to have four different groups.

If a molecule contains an internal plane of symmetry, its mirror image can be superimposed onto itself. This means the molecule is achiral overall and cannot show optical isomerism, despite having asymmetric-looking regions.

This is why careful inspection of the entire molecule, not just individual carbons, is important.

Glycine is the only common amino acid that does not contain a chiral centre.

Its central carbon is bonded to:

An amine group

A carboxylic acid group

Two identical hydrogen atoms

Because two substituents are the same, the carbon does not meet the requirement of four different groups and glycine is therefore achiral.

Yes, this is possible in some cases.

If a molecule has multiple chiral centres arranged symmetrically, the effects of each centre can cancel out. Such molecules are known as meso compounds, which are achiral despite containing chiral centres.

This concept goes beyond simple identification but helps explain why chirality must be assessed across the whole structure.

Enantiomers have identical physical properties such as boiling point, solubility, and density.

Because of this, standard separation techniques like distillation or filtration are ineffective. Separation usually requires a chiral environment, such as:

A chiral reagent

A chiral stationary phase in chromatography

This explains why enantiomer separation is a specialised process.

Biological systems are chiral, meaning they can distinguish between different enantiomers.

As a result:

One enantiomer may be therapeutically active

The other may be less effective or cause side effects

Understanding chirality allows chemists to design and test drugs more safely and effectively, making optical isomerism highly significant in medicine.

Practice Questions

Define optical isomerism and state the structural feature required for a molecule to show optical isomerism.

(2 marks)

Correct definition of optical isomerism as the existence of non-superimposable mirror images (1 mark)

Correct identification of a chiral centre as the required structural feature / carbon atom bonded to four different groups (1 mark)

The molecule shown below is an organic compound with the formula C4H9NO2.

a) Explain what is meant by a chiral centre. (2 marks)

b) State whether this molecule can show optical isomerism and give a reason for your answer. (2 marks)

c) Name one structural feature that would prevent a molecule from being optically active. (1 mark)

(5 marks)

a) (2 marks)

Definition of a chiral centre as a carbon atom attached to four different substituents (1 mark)

Clear reference to tetrahedral carbon or three-dimensional arrangement (1 mark)

b) (2 marks)

Correct statement that the molecule can show optical isomerism OR cannot show optical isomerism (1 mark)

Correct explanation linked to presence or absence of a chiral centre / four different groups attached to a carbon (1 mark)

c) (1 mark)

One correct feature stated, e.g.

Carbon bonded to two identical groups

Presence of a plane of symmetry

Double or triple bond preventing four different substituents