OCR Specification focus:

‘Consequences of the First World War; impact of the Treaty of Versailles; the Weimar Constitution’.

This topic examines Germany’s postwar crisis, how the Treaty of Versailles reshaped politics and economics, and how the new Weimar Constitution attempted democratic reconstruction domestically.

Germany in 1918–1919: Immediate consequences of the First World War

Germany emerged from total war facing profound disruption. The abdication of Kaiser Wilhelm II and the November Revolution swept away the imperial order and forced rapid democratisation amid scarcity and unrest. Demobilisation returned millions to civilian life, straining housing, employment and welfare provision.

Human and social costs: c.2 million war dead; many more wounded; wartime blockade effects lingered into 1919, with shortages, disease and malnutrition undermining productivity and morale.

Economic legacies: wartime borrowing and money creation generated inflationary pressure; factories experienced raw-material shortages; export markets were dislocated; government budgets were unbalanced.

Political fragmentation: parties multiplied and polarisation deepened as elites, workers and veterans advanced competing visions of Germany’s future; coalition bargaining became the norm.

National identity strain: defeat and armistice fostered resentment and the “stab-in-the-back” myth, weakening legitimacy for moderate leaders seeking compromise peace.

The Treaty of Versailles (1919): Terms and impact

The Allies imposed the Treaty in June 1919, binding the new republic to punitive measures that reshaped its economy, security and politics.

Treaty of Versailles: The peace settlement signed on 28 June 1919 that imposed territorial, military, financial and moral obligations on Germany as the defeated power.

The settlement’s content and symbolism fuelled domestic bitterness as many Germans perceived it as a Diktat (dictated peace).

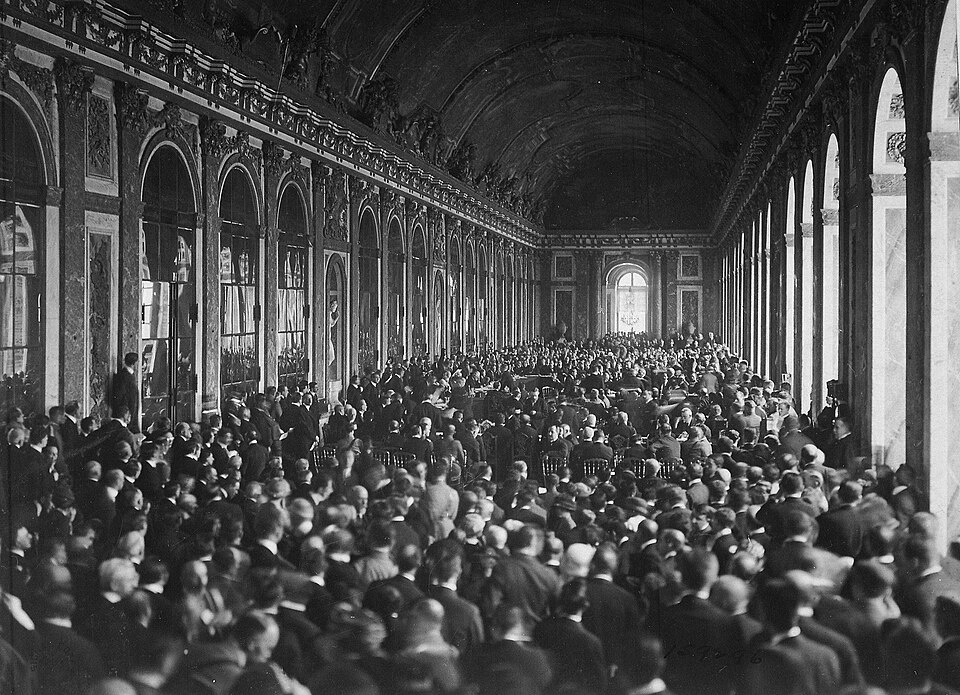

Delegates sign the Treaty of Versailles in the Hall of Mirrors at Versailles on 28 June 1919. The ceremonial table and crowded diplomatic scene symbolise the treaty’s political gravity and perceived humiliation. Source

Territorial and military restrictions

Loss of Alsace-Lorraine to France; creation of the Polish Corridor; Danzig as a Free City; Saar under League control; Anschluss with Austria forbidden.

Rhineland demilitarisation and Allied occupation zones, curtailing German strategic autonomy.

Army limited to 100,000 volunteers; no conscription, tanks, air force or submarines; navy capped to a small coastal force.

Financial and moral clauses

Reparations were to compensate Allied losses, later fixed at high levels, burdening public finances and external balances.

Article 231 (War Guilt Clause) assigned responsibility for the war, intensifying nationalist anger and providing agitators powerful propaganda.

Political and economic effects inside Germany

Delegitimisation of moderates: politicians who signed or implemented the treaty were branded “November Criminals”, complicating coalition formation and policy compromise.

Fiscal stress: reparations, loss of coal and iron, and trade disruptions constrained tax capacity and foreign-exchange earnings, feeding inflation and periodic payments crises.

Security anxiety: reduced forces and demilitarised zones heightened perceptions of vulnerability, strengthening appeals to revisionism and undermining faith in international guarantees.

The Weimar Constitution (1919): Structure and principles

The constitution, drafted at Weimar and adopted in August 1919, sought to embed liberal democracy and social rights while accommodating Germany’s federal traditions.

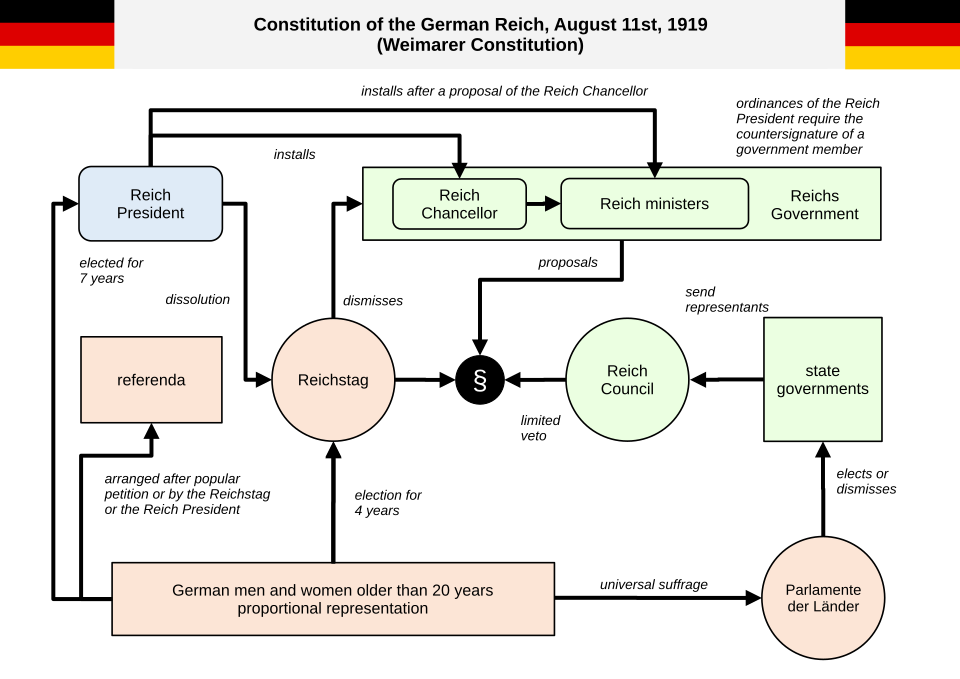

Schematic chart of the Weimar Constitution (1919–1933), showing the President, Reichstag, Reichsrat, Chancellor and Cabinet, and the electorate. Arrows clarify authority, accountability, and legislative roles. Source

Article 48: The emergency clause empowering the President to issue decrees and suspend civil liberties when public order and security were seriously disturbed or endangered.

Its framers balanced popular sovereignty with a strong head of state, hoping to safeguard order against crisis.

Proportional representation (PR): An electoral system allocating Reichstag seats in close proportion to each party’s national vote share via party lists.

Key institutions

President: directly elected for seven years; appoints and dismisses the Chancellor, can dissolve the Reichstag, commands the armed forces, and wields Article 48 powers.

Reichstag: main legislative chamber elected by PR; responsible for budgets, laws and holding government to account through confidence.

Chancellor and Cabinet: require Reichstag confidence to govern; command rests on coalition-building in a fragmented party system.

Federal structure: the Länder retained powers in education and policing; the Reichsrat represented Länder interests and could delay legislation.

Fundamental rights: guarantees of free speech, association, religion, equality before the law, and social protections reflected modern constitutionalism.

Strengths for a new democracy

Broad suffrage, including women’s suffrage from 1919, integrated citizens into national politics.

Codified rights and judicial review potential set legal barriers to arbitrary rule.

Federal checks via the Reichsrat moderated unitary excesses and recognised regional diversity.

Vulnerabilities and tensions

Fragmentation under PR: low thresholds encouraged many parties, complicating durable majorities and enabling small groups to act as kingmakers.

Dual executive ambiguity: the President’s democratic mandate rivalled Reichstag authority, making cabinet stability sensitive to presidential discretion.

Article 48 overreach: emergency rule, intended as a temporary safeguard, could normalise decree governance, eroding parliamentary norms during crises.

Referendums and polarisation: plebiscitary tools, while democratic, could be mobilised by anti-system actors to bypass parliamentary compromise.

Interactions: Versailles, postwar consequences and constitutional politics

The postwar shock and Versailles settlement framed the Weimar Republic’s early agenda: restoring order, stabilising the economy and reconciling national pride with international obligations. Material losses and reparations limited fiscal room for social investment just as mass expectations rose after wartime sacrifice. Politically, the constitution’s PR and rights offered inclusion, yet the stigma of defeat and the War Guilt Clause sharpened ideological cleavages. Presidents and chancellors navigated a landscape in which coalitions were fragile and Article 48 beckoned as a tempting expedient. For OCR study, link the consequences of the First World War to the impact of Versailles and assess how the Weimar Constitution’s design sought, yet sometimes failed, to contain those postwar pressures.

FAQ

The term “Diktat” was used because German representatives were excluded from the treaty negotiations and forced to sign without meaningful input.

This lack of participation reinforced the perception that Versailles was unjust, undermining the legitimacy of both the treaty and the Weimar politicians who accepted it.

The myth claimed Germany’s army had not been militarily defeated but instead betrayed by politicians and civilians at home.

By associating the Versailles settlement with this alleged betrayal, extremist groups portrayed democratic leaders as traitors and eroded public trust in the new republic.

Proportional representation was seen as the fairest system after imperial rule, ensuring all political voices were represented in the Reichstag.

However, the system led to fragmented parliaments where coalitions were unstable, and extremist parties could gain influence despite limited overall support.

Reparations created long-term fiscal strain, fuelling disputes over payment versus resistance.

Moderates argued for compliance to avoid Allied sanctions.

Nationalists and radicals demanded rejection, seeing payments as humiliation.

This tension polarised politics and kept Versailles central to debate.

It introduced democratic rights like universal suffrage and freedom of expression but also empowered the President with Article 48.

The aim was to safeguard democracy in emergencies, yet this mechanism risked undermining parliamentary authority when overused.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (2 marks)

Identify two territorial changes imposed on Germany by the Treaty of Versailles in 1919.

Mark Scheme for Question 1

1 mark for each correctly identified territorial change, up to a maximum of 2 marks.

Acceptable answers include:Alsace-Lorraine returned to France

The Saar placed under League of Nations control

Danzig made a Free City

Creation of the Polish Corridor (territory to Poland)

Eupen-Malmedy transferred to Belgium

Northern Schleswig to Denmark

Prohibition of Anschluss with Austria

Question 2 (6 marks)

Explain two political effects in Germany of the Treaty of Versailles (1919).

Mark Scheme for Question 2

Up to 3 marks for each effect explained, maximum of 6 marks.

1 mark for identifying the effect.

1–2 further marks for explaining how/why this effect occurred and its significance.

Indicative content:

Delegitimisation of moderate politicians: Those who signed the treaty were branded the “November Criminals,” undermining trust in the Weimar government.

Growth of nationalist resentment: The War Guilt Clause (Article 231) created widespread anger and fuelled extremist propaganda.

Coalition instability: Parties were divided over how to respond to Versailles, leading to fragile coalition governments.

Increased revisionist aims: Many politicians committed to revising or overturning Versailles, shaping foreign policy priorities.

Answers that only identify without explanation are capped at 2 marks per effect.