OCR Specification focus:

‘coalition governments; challenges to Weimar; Communist revolts, Kapp Putsch, Munich Putsch, invasion of the Ruhr, hyperinflation’

The early Weimar Republic faced serious instability. Political divisions, violent uprisings, economic collapse, and external pressures tested the fragile democracy and undermined confidence in government.

Coalition Governments in Weimar Germany

From the outset, the Weimar Republic relied on coalition governments due to its system of proportional representation. This voting system meant parties gained seats in the Reichstag according to their share of the national vote.

Proportional Representation: An electoral system in which parties receive seats in parliament in direct proportion to their share of the vote.

While this system ensured fairness, it also produced fragmented parliaments. No single party could dominate, forcing coalitions to form. Between 1919 and 1933, the Republic saw twenty separate governments, many lasting less than a year. This fostered political instability, as shifting alliances weakened public trust. Governments often collapsed before implementing meaningful reforms, leaving Germany vulnerable to crises.

Political Fragmentation

The Social Democratic Party (SPD), as the largest party, often struggled to maintain coalitions with centrist and liberal parties.

Conservative elites and the army remained suspicious of democracy, preferring authoritarian stability.

Extremist parties — the Communist Party (KPD) and National Socialists (NSDAP) — exploited instability, gaining support by denouncing parliamentary politics.

The constant turnover of governments made it difficult to tackle urgent crises effectively.

Communist Revolts

The Weimar Republic faced immediate threats from the radical left, inspired by the Russian Revolution.

The Spartacist Uprising, January 1919

Led by Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht, the Spartacist League attempted to seize power in Berlin. They sought to establish a workers’ state based on soviet-style councils. President Friedrich Ebert responded by calling upon the Freikorps (paramilitary ex-soldiers). The revolt was crushed brutally; Luxemburg and Liebknecht were executed.

This alienated many workers from the SPD, widening the gulf between moderate socialists and the far left.

Other Communist Threats

Ruhr uprising (1920): A workers’ revolt during the Kapp Putsch aftermath.

Periodic strikes and insurrections throughout the early 1920s, particularly in Saxony and Thuringia.

These revolts revealed the fragility of democratic order and the deep social divisions.

The Kapp Putsch, March 1920

The Weimar Republic also faced challenges from the right. Disgruntled army officers and nationalist groups opposed the Treaty of Versailles and the disbanding of Freikorps units.

Wolfgang Kapp, a right-wing journalist, and General Walther von Lüttwitz led a coup attempt in Berlin.

The legitimate government fled the capital.

The coup collapsed after general strikes paralysed the city, showing workers’ opposition to right-wing authoritarianism.

However, the leniency shown to Kapp’s supporters — compared with the harsh repression of communists — highlighted the judiciary’s bias against the Republic.

The Munich Putsch, November 1923

The most famous right-wing challenge was the attempted coup in Munich led by Adolf Hitler and the National Socialist German Workers’ Party (NSDAP).

Hitler sought to emulate Mussolini’s March on Rome, attempting to seize control of Bavaria before marching on Berlin.

Supported by Erich Ludendorff, they occupied a beer hall and declared a national revolution.

The putsch collapsed when police and army forces resisted. Sixteen Nazis were killed, Hitler arrested.

Though a failure, the Munich Putsch gave Hitler national publicity and convinced him to pursue power through legal political means.

The Invasion of the Ruhr, 1923

Germany’s economic struggles intensified with the issue of reparations under the Treaty of Versailles. When Germany defaulted on payments, French and Belgian troops occupied the Ruhr — Germany’s industrial heartland.

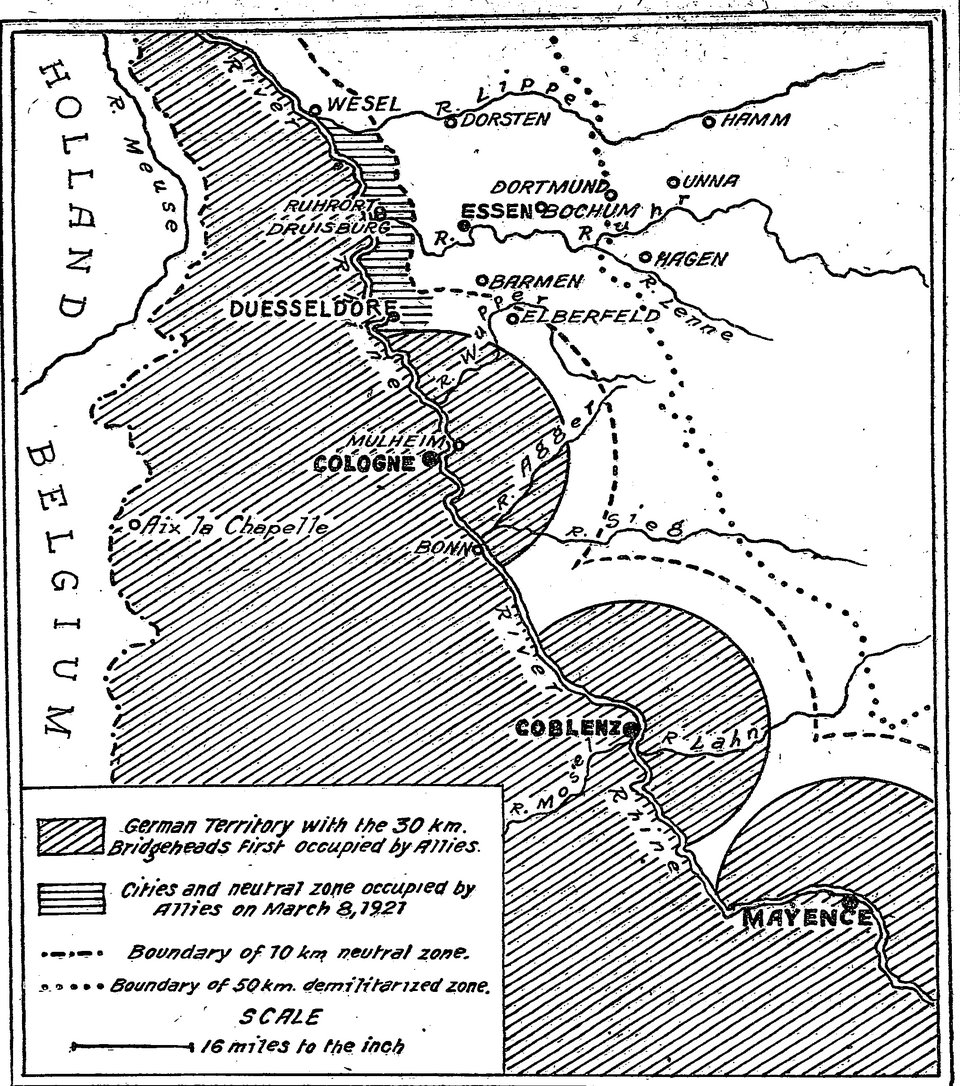

Contemporary map highlighting Essen and the Ruhr at the outset of the Franco-Belgian occupation, clarifying the geography behind passive resistance and production loss. The period labelling helps students situate events in January 1923. Source

The government encouraged passive resistance, with workers striking rather than cooperating.

Production collapsed, further reducing government revenue.

To fund striking workers, the government printed money, fuelling inflation.

The occupation humiliated Germany and deepened nationalist resentment.

Hyperinflation Crisis, 1923

The combination of war debt, reparations, and Ruhr resistance spiralled into hyperinflation, one of the defining crises of the Weimar Republic.

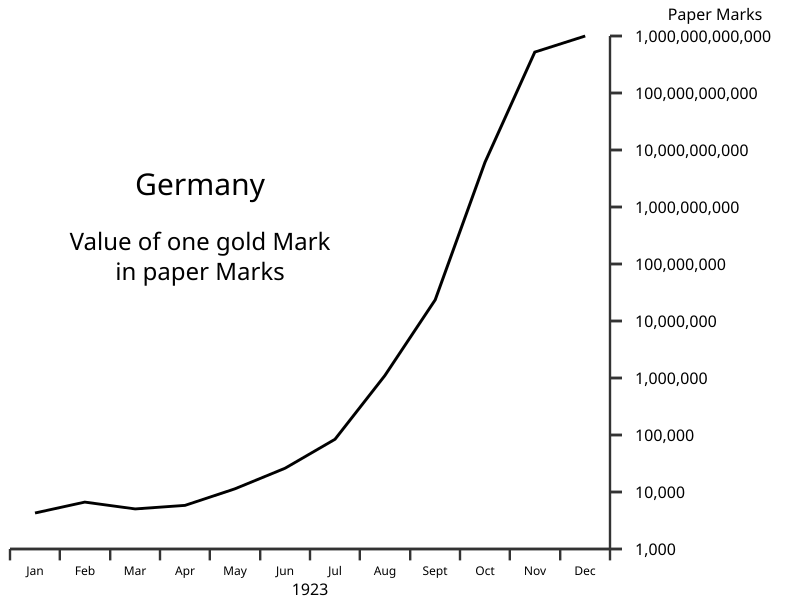

Logarithmic chart showing the 1923 price index surge during the Weimar hyperinflation, based on Bresciani-Turroni’s classic dataset. The rapidly rising curve illustrates the collapse of purchasing power. Source

Hyperinflation: An economic situation in which prices rise uncontrollably due to excessive expansion of the money supply, eroding the value of currency.

Key effects included:

Savings wiped out, destroying the middle class’s financial security.

Workers’ wages lost value within hours.

Barter replaced money in some areas.

Pensioners and those with fixed incomes suffered most.

While some with debts or mortgages benefitted, the broader population associated the crisis with government incompetence, further discrediting democracy.

Layered Impact of Weimar’s Challenges

Political: Frequent coalition collapses undermined faith in parliamentary democracy.

Social: Violence and polarisation between left and right deepened class conflict.

Economic: Reparations, Ruhr occupation, and hyperinflation eroded stability.

Psychological: National humiliation, insecurity, and resentment created fertile ground for extremist movements.

Together, these challenges explain why many Germans came to view Weimar democracy as weak and incapable of solving the nation’s problems, paving the way for future authoritarianism.

FAQ

The Freikorps were anti-communist and saw the Spartacists as a threat to order, so they assisted Ebert in crushing left-wing revolts.

However, when the government tried to disband them in line with Versailles’ restrictions, many Freikorps units turned against Weimar and supported the right-wing Kapp Putsch in 1920.

Wages became almost worthless within hours, forcing people to rush to spend their pay immediately.

Bartering for goods became common; farmers often refused money, demanding goods in exchange.

Savings and pensions collapsed, especially damaging the middle classes.

Meanwhile, some benefited: those with debts could repay them easily, and certain industrialists profited by paying off loans with inflated currency.

Judges often showed leniency towards right-wing rebels, such as those involved in the Kapp and Munich Putsches, handing out light sentences.

By contrast, left-wing revolutionaries, like Spartacist leaders and later communist agitators, were treated with severe repression.

This inconsistency created a sense that Weimar’s institutions were biased and unwilling to defend democracy impartially.

The Ruhr contained Germany’s industrial core, producing coal, steel, and manufactured goods vital for economic recovery and reparations payments.

Losing access to its output due to passive resistance crippled tax revenues and government finances.

The occupation also became a symbol of national humiliation, strengthening nationalist resentment against both the Allies and the Weimar government.

Although the putsch failed militarily, Hitler’s trial gave him national publicity as he portrayed himself as a patriotic defender of Germany.

His relatively light sentence reinforced perceptions of judicial sympathy for the right.

Most importantly, he concluded that power had to be achieved through legal, electoral means, shaping the Nazi Party’s future tactics in the 1920s.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (2 marks)

Identify two distinct challenges to the Weimar Republic between 1919 and 1923 named in the specification.

Mark scheme:

Award 1 mark for each valid identification, up to 2 marks.

Accept any two of: Communist revolts (e.g. the Spartacist Uprising, 1919), the Kapp Putsch (1920), the Munich Putsch (1923), the invasion of the Ruhr (1923), hyperinflation (1923).

Do not double-credit within the same category (e.g. “Communist revolts” and “Spartacist Uprising” together score 1 mark total).

Question 2 (6 marks)

Explain why coalition governments made it difficult for the Weimar Republic to deal with crises in the years 1919–1923.

Mark scheme:

Award up to 6 marks. Use a point-based approach: up to 2 marks per developed explanation point that links coalitions to difficulty managing crises, up to a maximum of three developed points.

For each developed point:

1 mark for a valid analytical point about coalitions (e.g. fragmentation, instability, conflicting aims).

+1 mark for specific supporting detail clearly linking the coalition issue to crisis management (e.g. reference to frequent cabinet changes “many lasting less than a year”; reliance on short-term measures against the Spartacists/Kapp; links to Ruhr passive resistance and inflation).

Indicative developed points (any three):

Proportional representation produced fragmented Reichstag arithmetic, so no single party could govern; short-lived coalitions (“many lasting less than a year”) hindered coherent responses to emergencies (2).

Coalition partners often disagreed over how to handle extremist threats; governments resorted to ad hoc measures (e.g. Freikorps against the Spartacists, general strike against Kapp) rather than stable policy, undermining authority (2).

Weak, shifting coalitions struggled to formulate sustainable economic policy during the Ruhr occupation, contributing to decisions (e.g. passive resistance and money printing) that intensified hyperinflation and public anger (2).

Typical performance bands:

1–2 marks: General assertions about “weak governments” with minimal linkage to crises.

3–4 marks: At least one explained link with some relevant detail; may be uneven.

5–6 marks: Two or more well-supported, clearly linked explanations drawing on accurate specifics from 1919–1923.