AP Syllabus focus:

‘Explain why carbon, hydrogen, and oxygen are the most prevalent elements in carbohydrates, proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids.’

Carbon, hydrogen, and oxygen dominate biological macromolecules because their electron structures favor stable covalent bonding, structural diversity, and useful interactions with water, enabling energy storage, information molecules, and cellular architecture.

Why C, H, and O Dominate Biological Molecules

Abundance and Accessibility

Hydrogen and oxygen are abundant in water, the most common biological solvent and reactant.

Carbon is widely available in (air) and dissolved inorganic carbon (aquatic systems), making it a central feedstock for building organic matter.

Covalent Bonding Suits Stable, Complex Structures

Carbon, hydrogen, and oxygen readily form covalent bonds that are stable under typical cellular temperatures and pH, allowing organisms to build large molecules that persist long enough to function but can still be broken down when needed.

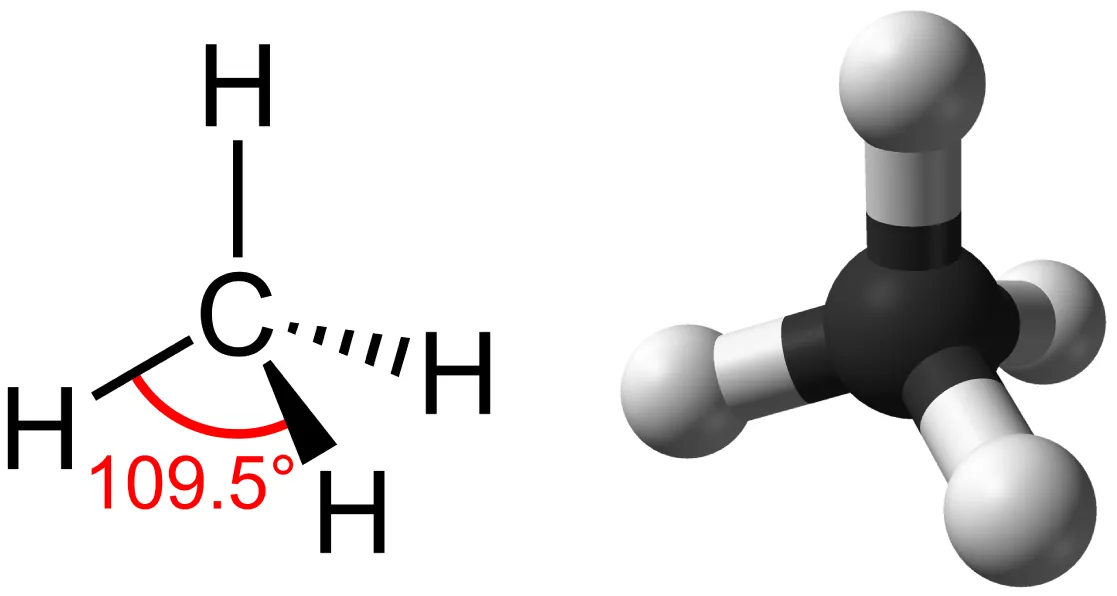

Tetravalent: Having four valence electrons available for bonding, allowing an atom (such as carbon) to form up to four covalent bonds.

Because carbon is tetravalent, it can serve as a versatile backbone while hydrogen and oxygen modify that backbone’s properties (shape, polarity, and reactivity).

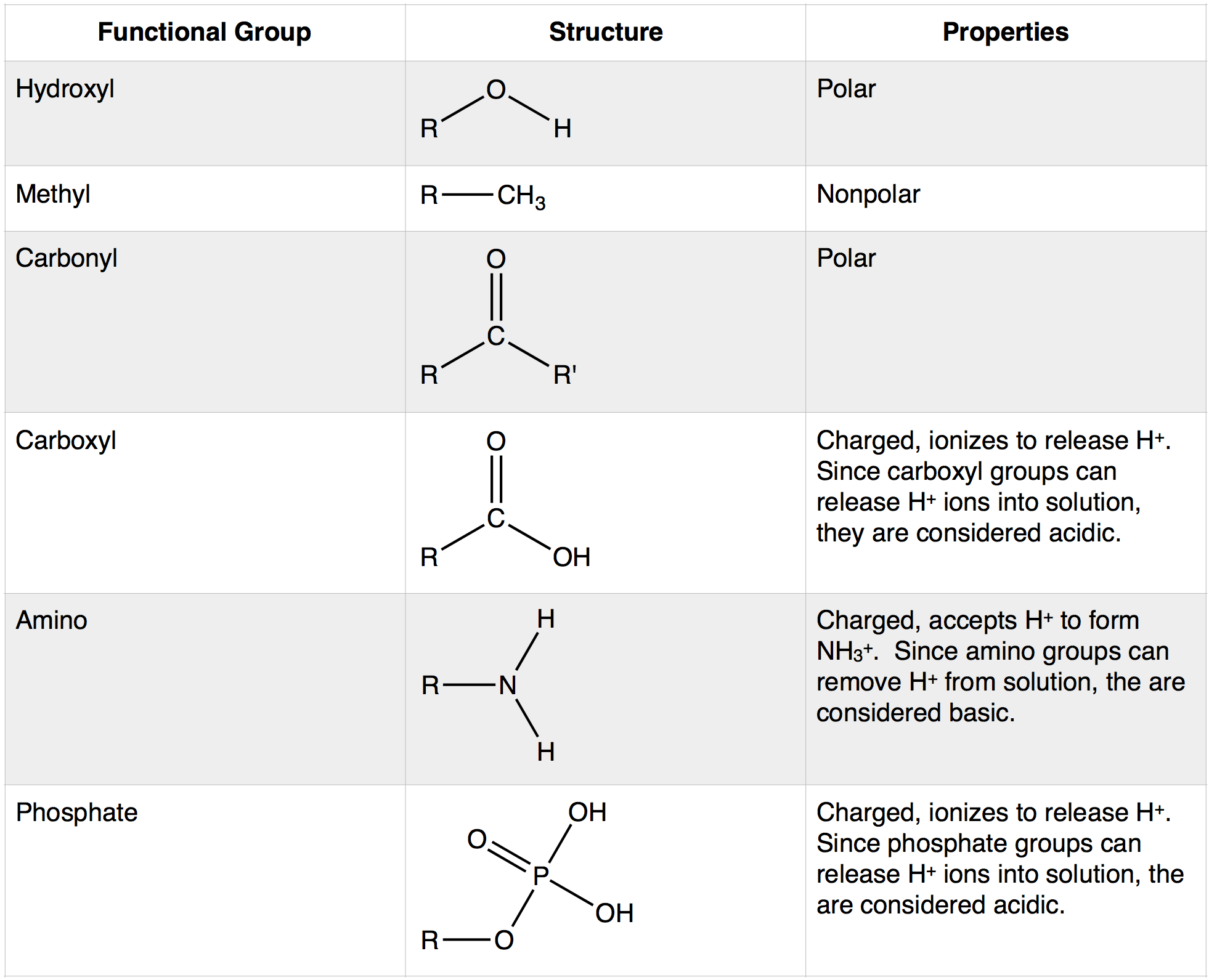

Carbon’s four covalent bonds produce predictable 3D geometries (e.g., tetrahedral methane). The figure also contrasts single- versus double-bonded carbon frameworks, showing how bond type changes molecular shape and rotational freedom—key to how carbon skeletons generate structural diversity in biomolecules. Source

Carbon: The Adaptable Backbone Element

Structural Versatility

Carbon forms single, double, and (less commonly in biology) triple bonds, enabling variation in shape and rigidity.

Carbon bonds to itself to make chains, branches, and rings, supporting diverse macromolecular architectures.

Carbon–carbon and carbon–hydrogen bonds are strong enough to be stable but can be rearranged through enzyme-catalysed reactions.

Functional Diversity Through Bonding Partners

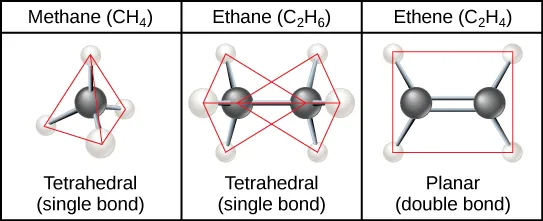

By bonding with oxygen and hydrogen, carbon frameworks gain functional groups (for example, hydroxyl-containing regions), creating many distinct molecules without requiring exotic elements.

The figure summarizes major functional groups commonly attached to carbon skeletons and highlights how specific atoms (especially oxygen and hydrogen) alter molecular properties. Seeing these groups side-by-side clarifies why adding O- and H-containing groups can dramatically change polarity, acidity/basicity, and interaction potential in water. Source

Hydrogen: Saturation, Shape, and Energy-Rich Bonds

Completing Carbon Skeletons

Hydrogen commonly bonds to carbon, “filling” available bonding positions and helping determine 3D shape and flexibility of carbon skeletons.

The number of hydrogens attached influences whether a region is more reduced (more C–H bonds) or more oxidised (more C–O bonds).

High Potential Energy in C–H Bonds

C–H bonds store substantial chemical energy; when organisms extract energy, electrons from these bonds can be transferred to other molecules in controlled pathways. This helps explain why molecules rich in carbon and hydrogen (especially hydrocarbon regions) are common in energy storage contexts.

= An organic molecule containing carbon, hydrogen, and oxygen

= Oxidant used in aerobic metabolism

= Carbon dioxide released after carbon is fully oxidised

= Water formed after hydrogen is oxidised

Oxygen: Polarity, Solubility, and Controlled Reactivity

Creates Polar Bonds and Hydrogen-Bonding Capacity

Oxygen is highly effective at creating polar covalent bonds (for example, C–O and O–H).

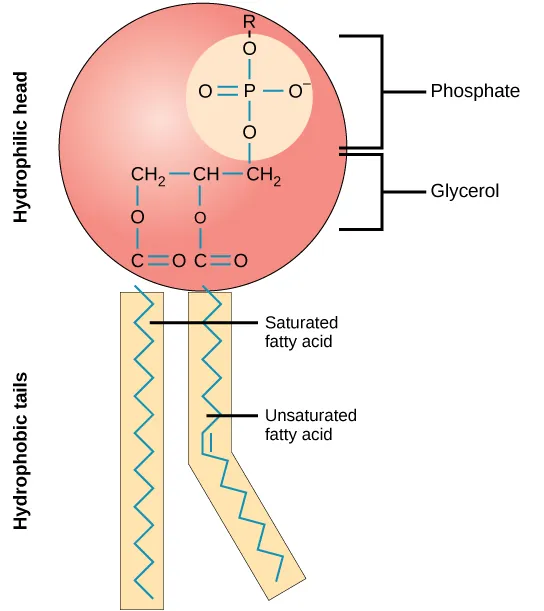

A phospholipid is shown as an amphipathic molecule with a polar, phosphate-containing head and two nonpolar hydrocarbon tails. This visual links oxygen-rich functional groups to hydrophilicity while highlighting how C–H-rich regions remain hydrophobic, explaining lipid behavior in water and membrane formation. Source

These polar regions:

Increase water solubility of many biomolecules and intermediates

Provide sites for hydrogen bonding, which stabilises molecular interactions and shapes in aqueous environments

Enables Chemical Reactivity Central to Metabolism

Oxygen-containing groups often form reactive sites where enzymes act, allowing:

Formation and breakage of bonds during synthesis and breakdown of macromolecules

Controlled electron transfer in energy-related reactions

How C, H, and O Appear Across Macromolecules (Overview)

Common Patterns that Explain Prevalence

Carbohydrates: built largely from C, H, and O; many hydroxyl-containing regions make them chemically versatile in water.

Lipids: contain extensive C–H regions that are energy-rich; comparatively less oxygen often corresponds to lower polarity.

Proteins and nucleic acids: although they require additional elements, their carbon backbones and many structural/functional features still rely heavily on C–H frameworks and oxygen-containing groups that tune polarity and reactivity.

FAQ

Lipids often have long hydrocarbon regions dominated by C–H bonds, which keeps them relatively non-polar. Carbohydrates typically have more C–O and O–H bonds, increasing polarity and interaction with water.

More O (especially O–H or C–O bonds) increases polarity and hydrogen-bonding capacity. A higher proportion of C–H bonds generally decreases polarity, reducing solubility in water.

Stability comes from strong covalent bonds and enzyme control. Cells use catalysts and compartmentalisation to channel reactions through specific pathways rather than allowing uncontrolled oxidation.

CO2 is small, diffusible, and widely available. Once carbon is incorporated into reduced carbon compounds, it can be rearranged into many structures because carbon bonding is flexible.

Carbon can form varied skeletons (linear, branched, cyclic) and different bond types (single/double). Small changes in carbon framework and placement of O/H create major differences in shape, polarity, and reactivity.

Practice Questions

Describe two reasons carbon is well suited to form the backbone of biological macromolecules. (2 marks)

Carbon is tetravalent and can form four covalent bonds (1)

Carbon can bond to itself to form chains/branches/rings and/or form single and double bonds to create diverse structures (1)

Explain why hydrogen and oxygen are prevalent in biological macromolecules and how each contributes to molecular properties and biological function. (6 marks)

Hydrogen commonly bonds to carbon, completing/saturating carbon skeletons and influencing molecular shape (1)

C–H bonds store chemical energy; more reduced (H-rich) regions have higher potential energy (1)

Oxygen forms polar covalent bonds with carbon and hydrogen (1)

Oxygen-containing regions increase solubility in water and/or allow hydrogen bonding with water/other molecules (1)

Oxygen-containing functional regions provide reactive sites for enzyme-catalysed reactions (1)

Link to macromolecules: e.g., lipids are relatively O-poor and energy-rich; carbohydrates are O-rich and more polar (1)