AP Syllabus focus:

‘Describe how atoms and molecules from the environment supply carbon, hydrogen, oxygen, nitrogen, phosphorus, and sulfur used to build biological macromolecules.’

Living organisms are made of matter that ultimately comes from the environment. A small set of elements—especially CHNOPS—is repeatedly assembled into the monomers and polymers that form cells, tissues, and biomolecules.

This diagram highlights the six major elements in living matter—carbon, hydrogen, nitrogen, oxygen, phosphorus, and sulfur (CHNOPS). It reinforces the idea that most biological macromolecules are constructed by rearranging this small set of atoms into different functional groups and polymers. Source

Essential Elements and Why They Matter

Organisms require certain chemical elements to build and maintain biological structures and to carry out metabolism. The same few elements recur because their bonding properties support stable, versatile biological molecules.

Essential element: A chemical element required for an organism’s normal growth, reproduction, or survival.

The “Big Six”: CHNOPS

Carbon (C), hydrogen (H), oxygen (O), nitrogen (N), phosphorus (P), and sulfur (S) make up the majority of living matter and are the main raw materials for biological macromolecules (carbohydrates, lipids, proteins, nucleic acids).

Environmental Sources of Atoms and Molecules

Organisms do not create elements; they obtain atoms in chemical forms present in their surroundings, then rearrange them via biochemical reactions.

Common Environmental Inputs (Typical Chemical Forms)

Carbon: primarily as carbon dioxide (CO₂) in air or dissolved in water; also as organic carbon in food for consumers

Hydrogen and oxygen: primarily from water (H₂O); oxygen also from O₂ (for aerobic respiration) and from CO₂/H₂O used in biosynthesis

Nitrogen: mainly as nitrate (NO₃⁻) or ammonium (NH₄⁺) in soil/water; atmospheric N₂ is abundant but largely unusable unless converted by certain microbes

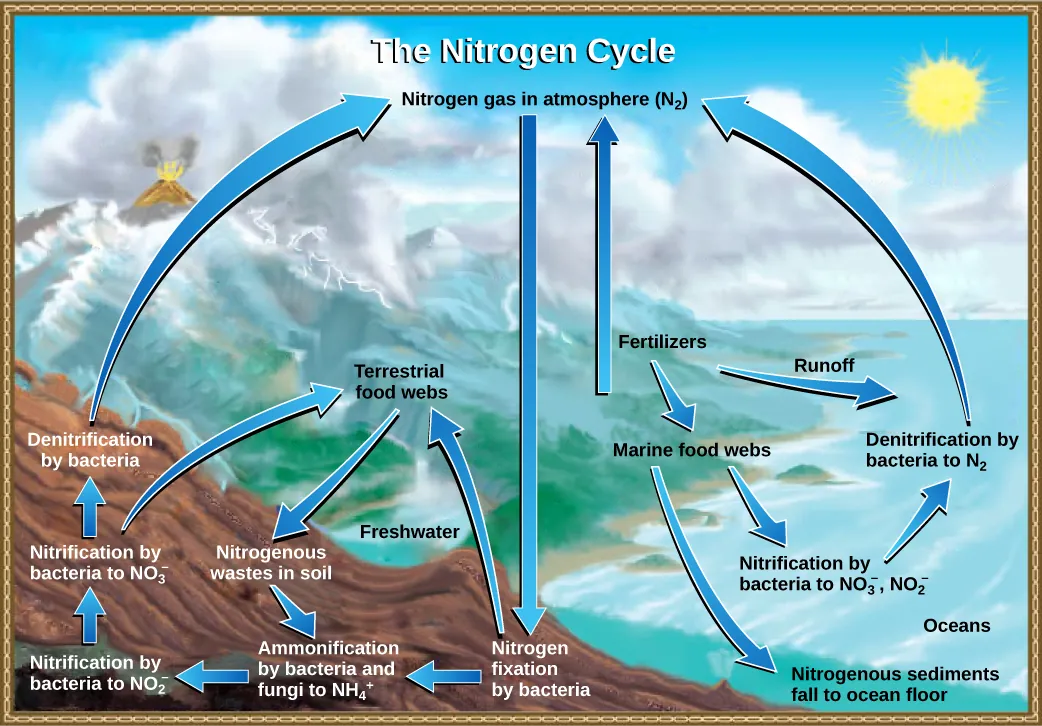

This figure summarizes how nitrogen moves between the atmosphere, soils/waters, and food webs. It emphasizes the major chemical forms organisms rely on (especially and ) and the bacterial processes that convert relatively inaccessible atmospheric into biologically usable nitrogen. Source

Phosphorus: typically as phosphate (PO₄³⁻) ions from minerals, soil, or aquatic systems

Sulfur: typically as sulfate (SO₄²⁻) or other sulfur-containing ions from rocks, soil, or water

How Organisms Acquire These Materials

Autotrophs (e.g., plants, algae) take in CO₂, H₂O, and mineral ions through gas exchange surfaces and roots (or aquatic equivalents), then synthesize organic molecules.

Heterotrophs (e.g., animals, fungi) obtain many atoms already packaged in organic molecules by eating, absorbing, and digesting other organisms or organic matter.

In both cases, atoms are conserved: they move between environment and organisms, then are returned through waste, decomposition, and other transfers.

Linking Elements to Biological Macromolecules

The central idea is that environmental atoms become the structural “parts list” for polymers. Each element contributes characteristic bonding patterns or functional groups that shape macromolecule properties.

Carbon, Hydrogen, and Oxygen: the Structural Framework

Carbon forms stable covalent bonds and carbon skeletons (chains, rings), allowing large, diverse molecules.

Hydrogen commonly bonds to carbon and oxygen, affecting molecular shape and energy content.

Oxygen contributes to polarity and reactivity (e.g., hydroxyl and carbonyl groups), influencing solubility and interactions in cells.

Nitrogen: Enabling Amino Groups and Bases

Nitrogen is a key component of:

Amino groups in amino acids, which are required to build proteins

Nitrogenous bases in nucleotides, which are required to build DNA and RNA

Because nitrogen is often acquired as nitrate or ammonium, organisms must incorporate it into organic molecules through enzymatic pathways.

Phosphorus: Energy Transfer and Nucleic Acid Backbones

Phosphorus commonly appears as phosphate groups, which are central to:

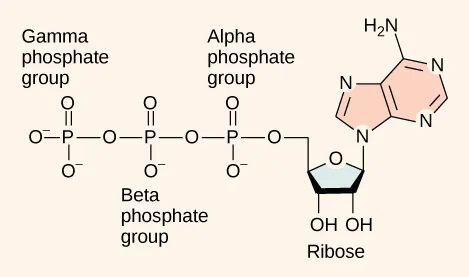

This structural diagram of ATP shows an adenosine backbone attached to three phosphate groups (α, β, γ). It provides a concrete molecular example of how phosphate groups are positioned to participate in energy-transfer reactions through phosphate removal and transfer. Source

The sugar-phosphate backbone of nucleic acids

Cellular energy transfer chemistry (phosphate-containing molecules are used broadly in metabolism)

Limited phosphate availability can constrain biosynthesis because nucleic acids and many regulatory molecules require phosphate.

Sulfur: Stabilizing Protein Structure and Function

Sulfur is incorporated into specific amino acids (notably those with sulfur-containing side chains), which can:

Contribute to protein folding and stability through sulfur-based linkages

Support enzyme activity and molecular recognition via distinctive chemical reactivity

Element-to-Macromolecule Map (High-Yield)

Carbohydrates: mostly C, H, O (carbon backbone with many oxygen-containing groups)

Lipids: mostly C, H, O (often lower O proportion than carbohydrates; properties depend on carbon-hydrogen richness)

Proteins: C, H, O, N (and sometimes S), reflecting amino acid composition

Nucleic acids (DNA/RNA): C, H, O, N, P, reflecting sugar, phosphate, and nitrogenous bases

FAQ

N2 has a very strong triple bond, making it chemically unreactive.

Only certain bacteria and archaea can convert N2 into usable forms (such as ammonium), which then enter food webs.

Phosphate often binds to minerals or becomes insoluble depending on pH and soil chemistry.

High runoff can remove phosphate from soils, while in water bodies phosphate can become trapped in sediments.

Nitrate is first reduced to nitrite and then to ammonium using enzymes and cellular energy.

Ammonium is then incorporated into carbon skeletons to form amino acids.

Sulfur is required for particular amino acids and for key catalytic features in some proteins.

Small sulfur shortages can disrupt protein structure and enzyme function.

Researchers use controlled growth experiments with purified diets/solutions lacking one element.

If removal prevents normal growth or reproduction and adding it back restores function, it supports essentiality.

Practice Questions

Identify two elements from CHNOPS and state one macromolecule each helps build. (2 marks)

Names any two correct elements from carbon, hydrogen, oxygen, nitrogen, phosphorus, sulfur (1 mark)

Correctly matches each named element to an appropriate macromolecule (e.g., nitrogen → proteins or nucleic acids; phosphorus → nucleic acids; sulfur → proteins; carbon → all macromolecules) (1 mark)

Explain how atoms from the environment supply organisms with the raw materials needed to build biological macromolecules. In your answer, refer to at least three of the elements in CHNOPS and describe typical environmental forms/sources. (5 marks)

States that organisms obtain atoms/molecules from the environment and rearrange them into macromolecules (1 mark)

Carbon source described (e.g., CO2 for autotrophs or organic carbon in food for heterotrophs) (1 mark)

Nitrogen source described (e.g., nitrate/ammonium; N2 requires microbial conversion) (1 mark)

Phosphorus source described (e.g., phosphate ions from soil/water/minerals) (1 mark)

Mentions hydrogen/oxygen from water and/or oxygen’s role as environmental input (1 mark)