AP Syllabus focus:

‘Explain that polysaccharide polymers formed from monosaccharides can be either linear chains or branched structures.’

Polysaccharides can be built as straight chains or with branch points, and this architecture strongly influences their shape, packing, and how easily enzymes can access their glycosidic bonds in cells.

Core Idea: Polymer Shape Depends on Bonding Pattern

Polysaccharide: a carbohydrate polymer made of many monosaccharide subunits covalently linked into long chains.

Polysaccharide architecture is determined by which hydroxyl (–OH) groups on the monosaccharides are joined during polymer formation. Different bonding patterns produce either a linear chain or a branched structure, even when the polymer is made from the same monosaccharide type.

Glycosidic Bonds as the “Connectors”

Glycosidic bond: a covalent bond that links two monosaccharides, formed when an –OH group on one sugar reacts with a carbon on another sugar, creating a stable linkage.

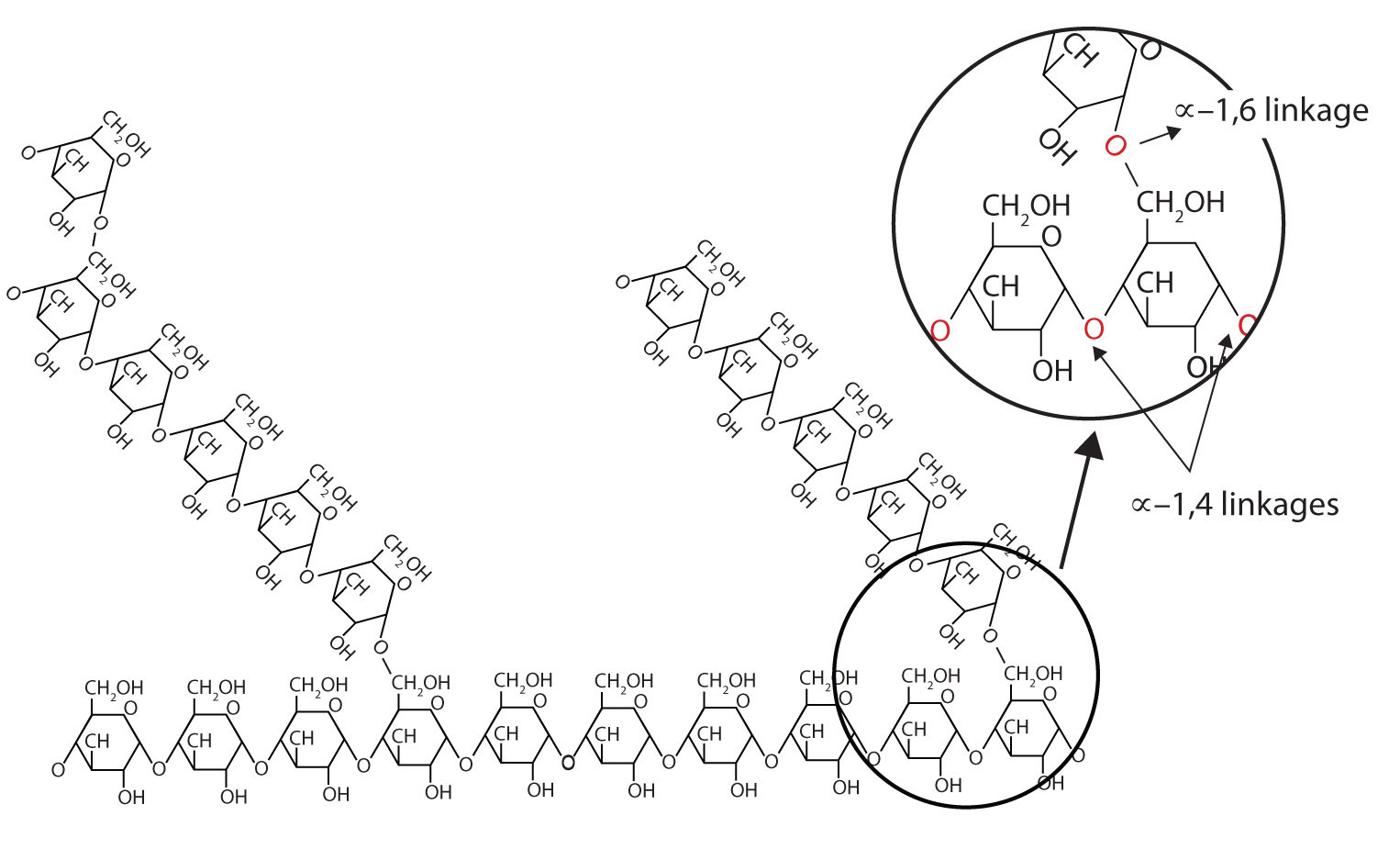

In many polysaccharides, a “main chain” is produced by repeating glycosidic bonds between specific carbons (often written as 1→4 linkages). Branching occurs when an additional glycosidic bond forms from a sugar in the main chain to a new sugar at a different carbon position (often written as 1→6 linkages).

This diagram highlights the two key glycosidic linkage types that determine polymer architecture: α-1,4 linkages extend the main chain, while α-1,6 linkages create branch points. By making new chain ends, branching increases the number of termini available for enzyme action and changes overall packing compared with a purely linear chain. Source

The key AP Biology takeaway is that the presence or absence of these branch-point linkages changes polymer shape.

Linear Polysaccharide Polymers

Structural Features

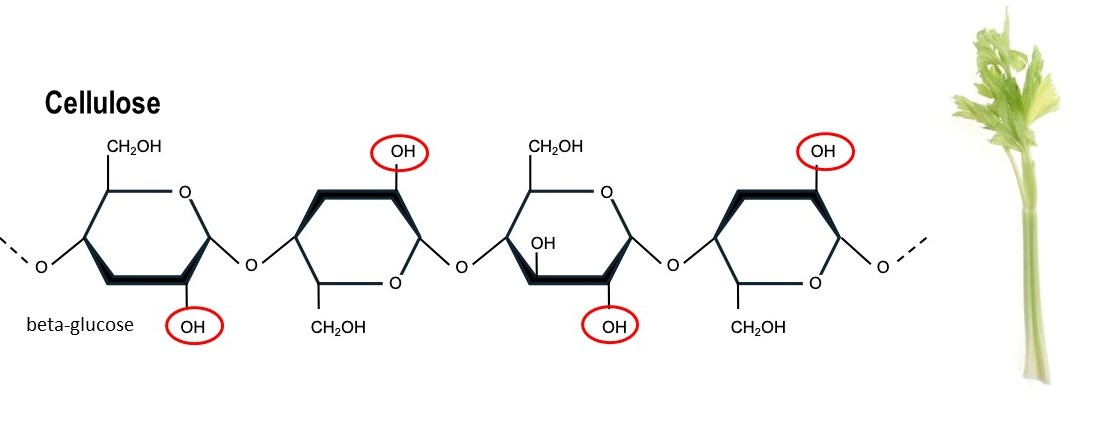

A linear polysaccharide is built as a single continuous chain of monosaccharides with no side chains.

This figure shows a linear polysaccharide chain built from repeating β(1→4) glycosidic bonds, producing an unbranched, extended architecture. The alternating orientation of successive glucose units illustrates how bonding geometry can enforce a straight, packable chain that can align closely with neighboring chains. Source

Each monosaccharide (except the ends) typically connects to two neighbours:

one “upstream” sugar and one “downstream” sugar in the same chain

The polymer has two distinct ends (often described as ends with different chemical properties), which can matter for how enzymes begin breakdown or modification

Linear chains can align alongside each other more easily than branched chains

Consequences for Shape and Packing

Because linear polymers are unbranched, they can form long, extended structures or coil in predictable ways depending on bond angles. In general:

Linear chains can pack closely together when multiple chains align

Close packing can increase the stability of the overall material

Close packing can also reduce immediate access to internal bonds, since fewer chain segments are “exposed” on the surface

Branched Polysaccharide Polymers

Structural Features

A branched polysaccharide contains a main chain with one or more side chains created by branch-point glycosidic bonds.

Some monosaccharides in the main chain connect to three neighbours:

two along the main chain plus one leading into a branch

Branch frequency can vary:

occasional branching produces a mostly linear molecule with a few side chains

frequent branching produces a dense, bushy structure with many ends

Consequences for Shape and Accessibility

Branching changes both the three-dimensional shape and how the polymer interacts with water and enzymes.

Branched polymers tend to be more compact overall than equally long linear chains

Branching creates many chain ends

more ends can provide more starting points for enzymes that add or remove monosaccharides at ends

The compact, highly “ended” structure can increase the rate at which a cell can mobilize or remodel the polymer when needed

Why Linear vs Branched Matters Biologically (Without Specific Examples)

Enzyme Access and Reaction Rate

Cells often rely on enzymes that recognise particular glycosidic bonds and act at accessible regions.

Linear polymers may present fewer accessible sites at once if tightly packed or aligned

Branched polymers typically present more accessible chain ends, which can increase how quickly enzymes can act on the polymer as a whole

Mechanical and Spatial Properties

Polysaccharide architecture influences physical behaviour at the macromolecular level.

Linear chains are more likely to form extended arrays when multiple chains align, supporting rigid or fibrous organisation in some contexts

Branched chains tend to occupy space in a more globular, compact way, which can suit storage in limited cellular volume

Interactions with Water and Other Molecules

Branching can alter how a polysaccharide presents hydroxyl groups to the surrounding environment.

More branching often increases the number of exposed regions that can interact with water

Changes in exposure and packing can influence how readily the polymer hydrates and how it behaves in concentrated cellular solutions

What to be Able to State Clearly for AP Biology

Polysaccharide polymers can be either linear chains or branched structures.

The difference arises from where glycosidic bonds form along the monosaccharide subunits.

Branch points create additional chain ends and change polymer shape, packing, and enzyme accessibility.

FAQ

No. Branch frequency varies widely.

Some polymers have rare branch points (sparse branching)

Others branch very frequently, creating many short side chains and many ends

Branching often reduces chain entanglement compared with long straight chains.

This can lower viscosity at the same concentration, though the exact effect depends on polymer length, branch frequency, and how strongly chains interact with water.

Each new branch introduces an additional terminal end.

Many carbohydrate-processing enzymes interact at or near chain ends, so more ends can increase the number of simultaneous enzyme interactions, speeding up modification or breakdown.

It can fold or coil. “Linear” means unbranched, not necessarily straight.

Bond angles and repeated linkages can promote helical or extended conformations depending on the specific linkage geometry.

Look for any monosaccharide bonded to three other monosaccharides.

In drawings, this appears as a junction where one sugar connects along the main chain and also connects to a side chain via an additional glycosidic bond.

Practice Questions

State the difference between a linear polysaccharide and a branched polysaccharide. (2 marks)

Linear polysaccharide consists of a single unbranched chain of monosaccharides (1)

Branched polysaccharide has a main chain with side chains/branch points (1)

Explain how branching in a polysaccharide can affect its overall shape and how readily enzymes can act on it. (5 marks)

Branching creates branch points producing side chains from a main chain (1)

Branched polymers are generally more compact/globular than equally long linear chains (1)

Branching increases the number of chain ends (1)

More chain ends provide more sites for enzymes that act at ends to bind/start reactions (1)

Therefore enzymes can act more rapidly on a branched polymer overall than on a comparable linear polymer (1)