AP Syllabus focus:

‘Describe examples of important polysaccharides, including cellulose, starch, and glycogen, and relate their structures to their biological roles.’

Polysaccharides are major carbohydrate polymers whose biological roles depend on how their monosaccharides are linked and arranged. Small structural differences (bond type, branching) produce big functional differences in energy storage and structural support.

Core Idea: Structure Determines Function

What Makes a Polysaccharide “Different”?

Polysaccharides are built from repeating monosaccharides (often glucose) joined by covalent glycosidic linkages. The linkage type and branching pattern affect:

Overall shape (straight, helical, or branched)

Strength (ability to form many hydrogen bonds)

Accessibility to enzymes (speed of synthesis and breakdown)

Compactness (efficient packing for storage)

Polysaccharide: A carbohydrate polymer made of many monosaccharides covalently linked, used primarily for energy storage or structural support.

A key comparison in AP Biology is alpha (α) vs beta (β) glycosidic linkages between glucose monomers, because these orientations change 3D structure and enzyme compatibility.

Starch: Plant Energy Storage Polysaccharide

Biological Role

Starch stores glucose in plants for later energy release (e.g., in seeds, tubers, and roots). It is generally suited for storage because it is compact and can be hydrolysed when needed.

Structural Features that Support Storage

Starch is a mixture of two glucose polymers:

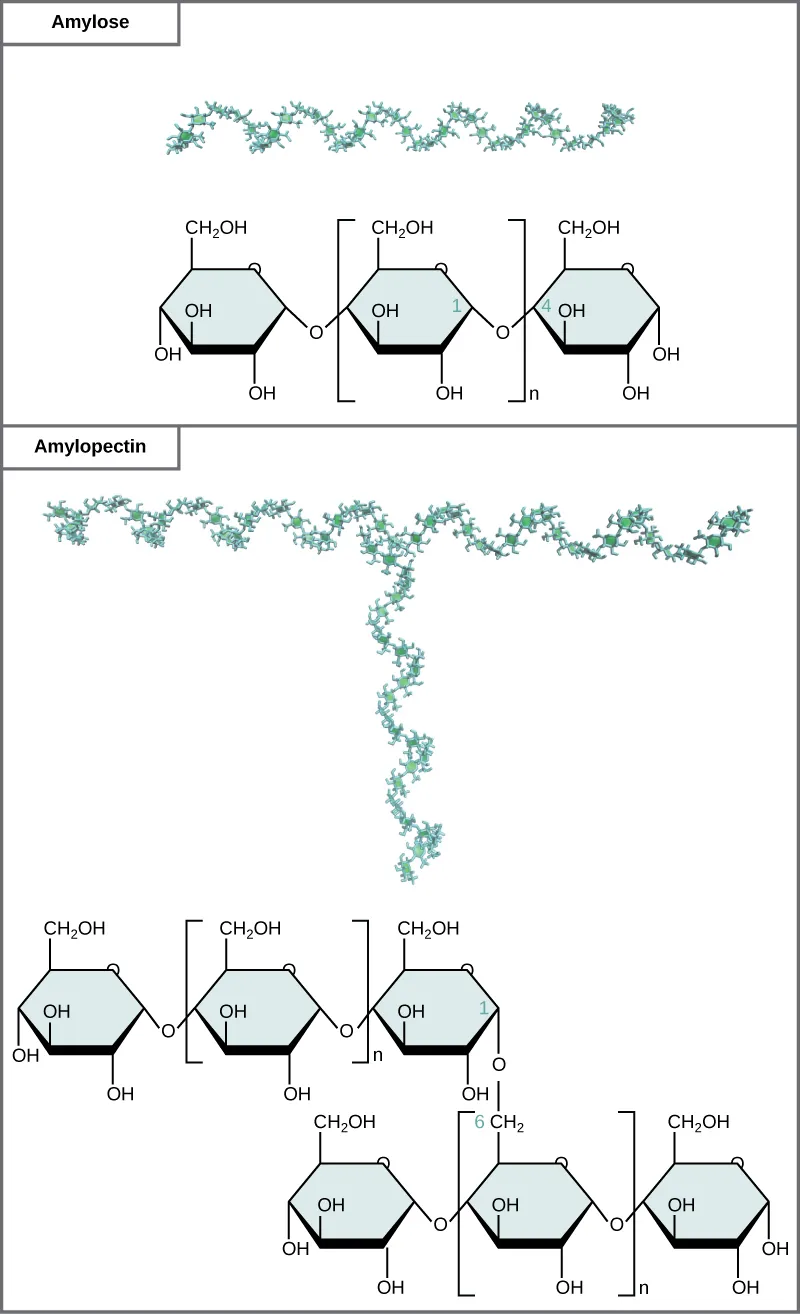

Amylose and amylopectin are contrasted as two starch polymers built from glucose: amylose is largely unbranched with α-1,4 glycosidic linkages, while amylopectin contains α-1,6 branch points in addition to α-1,4 linkages. The figure highlights how branching creates multiple chain ends, which increases enzymatic access and can speed glucose mobilization from storage. Source

Amylose: mostly unbranched glucose chain with α-1,4 linkages

Tends to form a helix, aiding compact storage

Amylopectin: branched polymer with α-1,4 linkages and α-1,6 branch points

Branching creates many ends for enzymes to act on, enabling faster mobilisation than amylose alone

Structure–Function Connections

α-linkages produce shapes more readily broken down by common enzymes, supporting a storage role.

Branching (amylopectin) increases the number of terminal glucose units, improving the rate of glucose release when plants need energy.

Glycogen: Animal (and Fungal) Energy Storage Polysaccharide

Biological Role

Glycogen is the main glucose storage polysaccharide in animals (notably liver and muscle cells) and also occurs in fungi. It supports short-term energy demands by allowing rapid glucose release.

Structural Features that Support Rapid Energy Release

Glycogen is similar to amylopectin but more highly branched:

Glucose monomers connected by α-1,4 linkages

Frequent α-1,6 branch points (more frequent than in amylopectin)

Structure–Function Connections

Extensive branching creates many enzyme-accessible ends, enabling very rapid hydrolysis when energy demand increases.

Compact, branched architecture allows substantial glucose storage in a small cellular volume, supporting active tissues.

Cellulose: Structural Polysaccharide in Plant Cell Walls

Biological Role

Cellulose provides structural support and protection in plant cell walls. Its architecture helps cells resist osmotic swelling and contributes to overall plant rigidity.

Structural Features that Support Strength

Cellulose is a glucose polymer with β-1,4 linkages, producing:

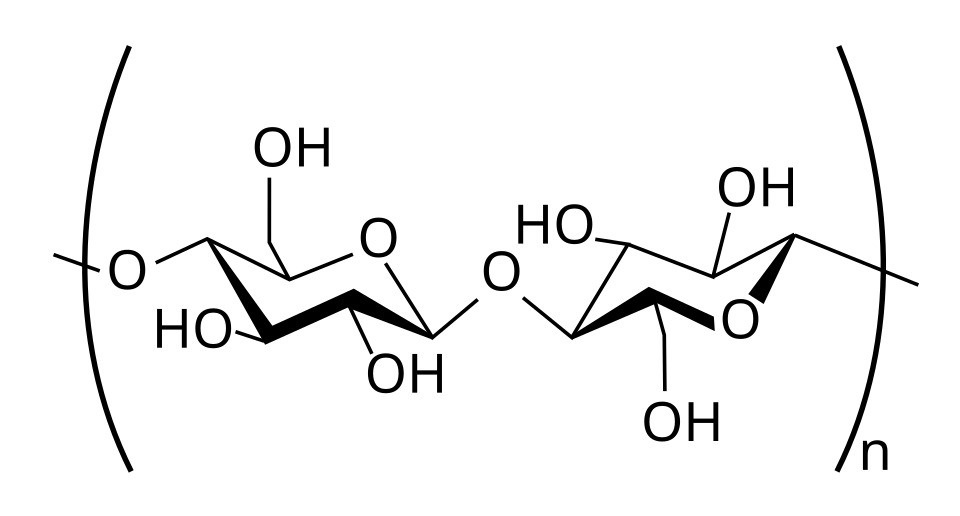

This skeletal structure depicts cellulose as a repeating polymer of glucose linked by β-1,4 glycosidic bonds, emphasizing the stereochemistry that leads to a straight, extended chain. Seeing the repeated β linkage helps explain why adjacent chains can align closely and form many stabilizing interactions in microfibrils. Source

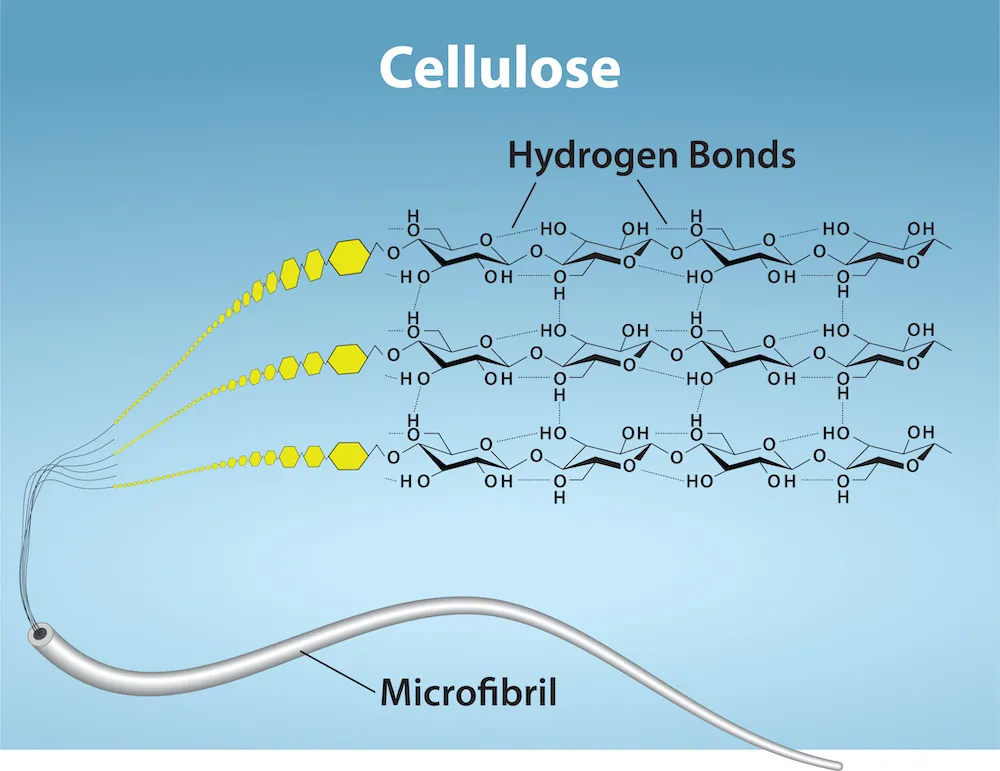

This diagram shows cellulose chains aligned side-by-side and stabilized by extensive hydrogen bonding, forming a strong microfibril. It visually connects β-linked, straight chains to tight packing and high tensile strength in plant cell walls. Source

Straight, unbranched chains

Alignment of many chains side-by-side into microfibrils

Extensive hydrogen bonding between adjacent chains, creating high tensile strength

Cellulose microfibril: A strong cable-like bundle formed when many cellulose chains align and hydrogen bond, strengthening plant cell walls.

Structure–Function Connections

β-linkages promote linear chains that pack tightly, maximising hydrogen bonding and mechanical strength.

The strong microfibril network makes cellulose well-suited for structure, not quick energy release; many animals lack enzymes to efficiently hydrolyse β-1,4 bonds.

Comparing Polysaccharides by Role

Key contrasts that link structure to function:

Starch vs glycogen (storage): both use α-linkages; glycogen’s greater branching supports faster glucose release in animals.

Cellulose (structure) vs storage polymers: β-linkages create straight chains and strong fibres; storage polymers prioritise enzyme accessibility and compactness over tensile strength.

FAQ

Human digestive enzymes recognise and hydrolyse alpha glycosidic linkages efficiently.

Beta-1,4 linkages in cellulose require specialised enzymes (cellulases), which humans do not produce.

More branches create more terminal ends.

Enzymes that remove glucose units can work on many ends at once, increasing the rate of mobilisation during high demand.

Amylose is mostly unbranched and tends to coil, contributing to compact storage.

Amylopectin is branched, providing more ends for enzymes, so it is mobilised more readily than amylose.

It is concentrated in liver and skeletal muscle cells.

These tissues need rapid access to glucose: the liver helps stabilise blood glucose, while muscles fuel contraction.

Parallel chains form many hydrogen bonds, bundling into microfibrils.

Microfibrils distribute forces across a network, resisting stretching and helping maintain cell shape under turgor pressure.

Practice Questions

State one structural feature of cellulose and explain how it relates to cellulose’s function in plants. (2 marks)

Identifies a correct structural feature (e.g., beta-1,4 linkages, straight unbranched chains, microfibrils, hydrogen bonding between chains). (1)

Links the feature to function (e.g., increased tensile strength/rigidity for cell walls; resistance to stretching/osmotic pressure). (1)

Compare starch, glycogen, and cellulose by describing how differences in glycosidic linkages and branching relate to their biological roles. (6 marks)

Starch is a plant storage polysaccharide made of alpha-glucose with alpha linkages (alpha-1,4; amylopectin also alpha-1,6). (1)

Glycogen is an animal/fungal storage polysaccharide with alpha-1,4 linkages and many alpha-1,6 branches. (1)

Glycogen is more highly branched than starch/amylopectin. (1)

Branching increases the number of chain ends, enabling faster glucose release. (1)

Cellulose is a structural polysaccharide with beta-1,4 linkages producing straight chains. (1)

Straight chains hydrogen bond into microfibrils, giving high tensile strength suited to cell walls. (1)