AP Syllabus focus:

‘Classify limit problems by the type of expression, such as rational, radical, trigonometric, or piecewise, as a first step toward choosing an effective solution method.’

This section introduces how recognizing the structural form of a limit problem guides your choice of strategy, helping you identify efficient methods before beginning any computation.

Classifying Limit Problems by Structure

Understanding the structure of a limit expression is essential because different algebraic forms behave predictably near points of interest. By categorizing a limit according to its form—rational, radical, trigonometric, polynomial, or piecewise—you can quickly anticipate which procedures are most effective. This reduces trial-and-error and builds a systematic approach to evaluating limits. The AP specification emphasizes using structure recognition as the first step in selecting an appropriate method.

Why Structure Matters

Limit expressions arise from many types of functions, and each type typically pairs with a reliable strategy. Recognizing the form early streamlines the problem-solving process and clarifies whether direct substitution, algebraic manipulation, limit laws, or theorem-based reasoning is appropriate. Because different expressions exhibit characteristic behaviors near the point of approach, structural classification functions as a diagnostic tool.

Major Structural Categories of Limit Problems

Rational Expressions

A rational expression is a ratio of two polynomials.

Rational expression: A function of the form f(x) = P(x)/Q(x) where P and Q are polynomials and Q(x) ≠ 0 on its domain.

Rational limits often suggest attempting direct substitution first, since polynomials are continuous everywhere.

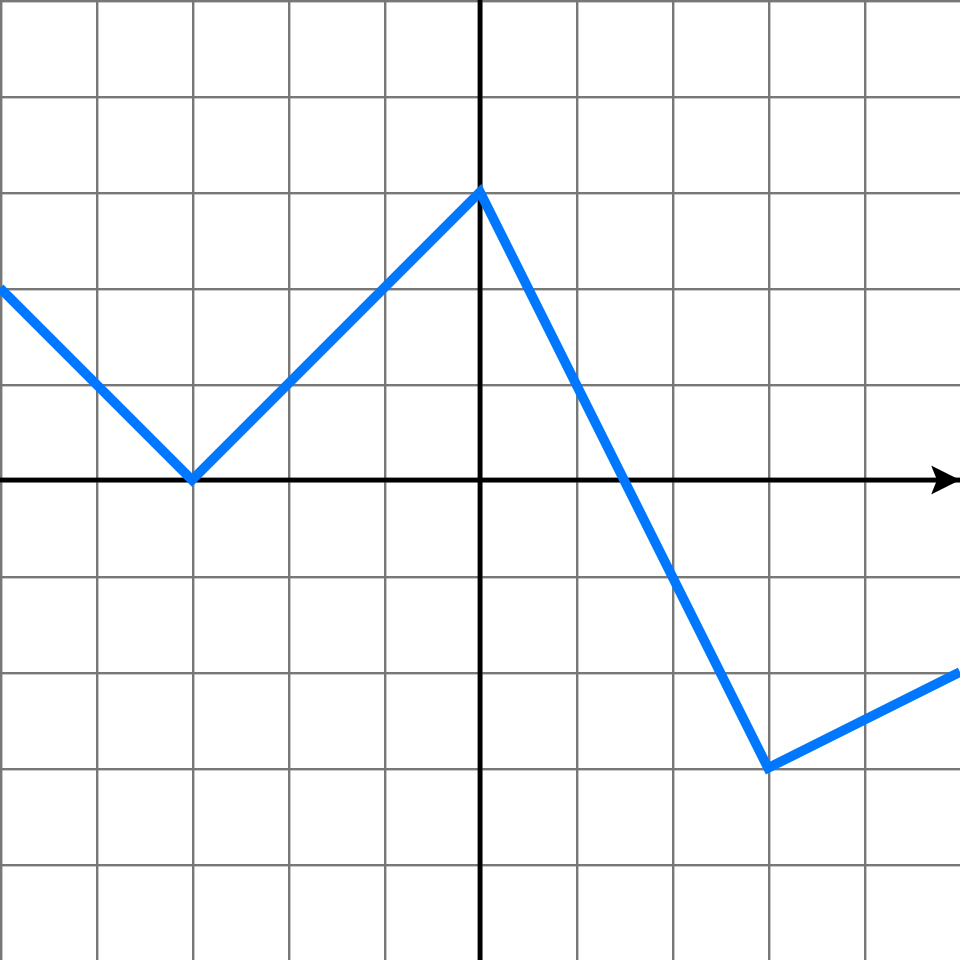

This graph shows a piecewise linear function composed of line segments that change direction at interval boundaries. It visually reinforces how piecewise structure requires examining left- and right-hand behavior at transition points. The function is not labeled with limits, but its shape highlights the domain segmentation essential in structural classification. Source.

Radical Expressions

A radical expression contains square roots or other roots that influence continuity and algebraic behavior. Students should pay attention to domain restrictions and to the structure of nested radicals. Radical limits frequently require simplification techniques such as multiplying by a conjugate to address indeterminate forms and produce an equivalent expression more amenable to evaluation.

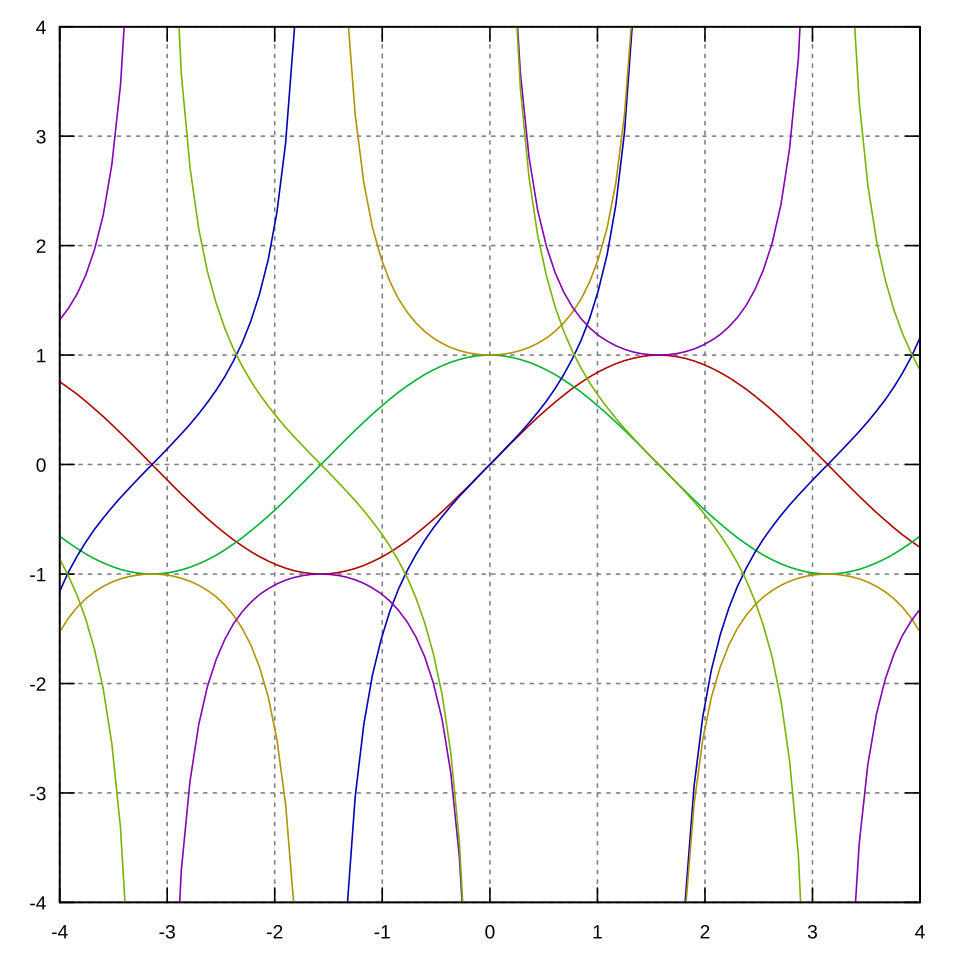

Trigonometric Expressions

Trigonometric limits rely on characteristic oscillatory behavior. Effective strategies depend on recognizing whether the limit involves standard forms such as sin(x), cos(x), or tan(x), particularly near x = 0. Structure classification helps determine whether substitution suffices, whether identities should be applied, or whether the problem will require fundamental limit results or the squeeze theorem.

This panel displays the six basic trigonometric functions, highlighting periodicity and the presence of vertical asymptotes in several functions. The variety of curve behaviors illustrates why structure strongly influences limit strategy, especially near points where oscillation or asymptotes occur. Some functions exceed the typical AP emphasis, but they collectively strengthen recognition of trigonometric structural patterns. Source.

Polynomial Expressions

Polynomials are structurally simple because they are continuous for all real x. Consequently, once a limit is identified as polynomial, direct substitution is usually appropriate. When a polynomial appears within a larger compound expression, structural classification helps isolate this continuous portion and may simplify the entire limit.

Piecewise-Defined Expressions

A piecewise-defined function has different formulas on different intervals, making structure especially relevant near boundary points.

Piecewise-defined function: A function described by multiple expressions, each applying to a specified region of the domain.

For these problems, left-hand and right-hand behavior must be analyzed separately. Recognizing that the structure itself changes at a point alerts you that equalizing these side behaviors is essential for determining the limit.

Indicators Used to Classify Structure

Presence of Specific Algebraic Features

Students should scan for elements such as:

Factored or factorable polynomial forms

Roots suggesting conjugate methods

Trigonometric expressions requiring identities

Mixed expressions combining several structural types

These indicators help determine whether simplification, identity substitution, or piecewise evaluation will be necessary.

Continuity Clues from Structure

Some categories, such as polynomials and many rational functions with nonzero denominators at the point of interest, are continuous on their domains. Recognizing continuity allows immediate use of substitution, avoiding unnecessary manipulation. On the other hand, structural features like denominators approaching zero, nested radicals, or oscillating trigonometric components warn that further analysis is required.

Identifying Structural Combinations

Many limit expressions combine multiple categories. Students should subdivide complex expressions to identify dominant structures. For instance, a rational expression containing trigonometric functions may require both algebraic limit laws and trigonometric identities. Recognizing layered structure leads to more efficient strategy decisions.

How Structural Classification Guides Method Selection

Matching Structure to Method

Classifying by expression type directs you toward the most common and effective approaches:

Rational → Attempt substitution, then factor and cancel if needed.

Radical → Rationalize or simplify to remove problematic radicals.

Trigonometric → Apply identities or known foundational limits.

Piecewise → Evaluate limits from each side independently.

Polynomial → Substitute directly due to inherent continuity.

Choosing the procedure based on structure aligns with the AP goal of building a flexible decision strategy.

Avoiding Inefficient Approaches

Structural classification prevents misapplication of methods. For example, attempting to factor a trigonometric limit or trying to apply conjugates to a polynomial expression wastes time and may introduce errors. Structure-based reasoning ensures that each problem begins with a targeted, mathematically justified approach.

Building Habits of Structural Awareness

Students benefit from adopting a quick, consistent scanning routine whenever they encounter a limit. This routine should include:

Identifying the dominant expression type or types

Noting features that restrict the domain

Checking immediately whether substitution is valid

Selecting methods aligned with the recognized structure

Developing this habit enhances mathematical efficiency and aligns with the syllabus requirement to classify limit problems before selecting a solution method.

FAQ

Look for the component that most strongly influences behaviour near the point of approach. This is typically the part that becomes undefined, oscillatory, or produces an indeterminate form.

A useful strategy is to scan the expression in layers:

• Identify any denominators or radicals that may restrict the domain.

• Look for oscillatory trigonometric components.

• Determine which component prevents direct substitution.

The dominant structure is the one whose properties dictate the limit method required.

A removable discontinuity usually indicates that a rational expression has a factor in common between the numerator and denominator. This structural feature signals that algebraic simplification will be effective.

Spotting a potential hole early helps avoid unnecessary techniques, such as numerical estimation or trigonometric identities, which would be inefficient or irrelevant.

A structure that oscillates between fixed bounds, especially trigonometric expressions near zero, hints at bounding behaviour. While not solved in this subsubtopic, recognising the structure alerts you that traditional algebraic methods may be insufficient.

Look for:

• Expressions containing sine or cosine multiplied by shrinking factors.

• Functions whose magnitude is clearly limited by simpler expressions.

Structural analysis reveals what the function must do mathematically, independent of graphical distortions such as scaling or resolution.

For instance:

• A denominator approaching zero indicates steep behaviour even if the graph appears smooth.

• A piecewise boundary may be visually obscured but still demands checking both sides.

Thus, recognising structure prevents overreliance on potentially deceptive visual cues.

Yes. Even when substitution works, classifying structure builds habits that reduce mistakes on more complex problems.

Additionally, quick structural checks help confirm that:

• No hidden discontinuities exist.

• No unexpected domain restrictions affect the value.

• The chosen method is the most efficient.

Consistent classification leads to faster, more accurate decision-making on exam problems.

Practice Questions

(1–3 marks)

A function g is defined by the expression g(x) = (x + 2)/(x − 3).

By examining the structure of the expression, determine whether the limit of g(x) as x approaches 3 can be found using direct substitution or whether an alternative method is required. Justify your answer.

(1–3 marks)

• 1 mark for identifying that g(x) is a rational expression.

• 1 mark for stating that direct substitution leads to division by zero at x = 3.

• 1 mark for concluding correctly that the limit cannot be evaluated by substitution and requires alternative analysis due to the zero denominator.

(4–6 marks)

Consider the function h defined as follows:

h(x) = x + 1 for x < 0

h(x) = x^2 + 1 for x ≥ 0

(a) Classify the structure of the limit problem at x = 0 and explain why classification is necessary.

(b) Determine the left-hand and right-hand limits of h(x) as x approaches 0.

(c) State whether the limit of h(x) as x approaches 0 exists, giving a reason.

(4–6 marks)

(a)

• 1 mark for correctly identifying the problem as involving a piecewise-defined function.

• 1 mark for explaining that this classification indicates that one-sided limits must be evaluated separately.

(b)

• 1 mark for correctly computing the left-hand limit using x + 1.

• 1 mark for correctly computing the right-hand limit using x^2 + 1.

(c)

• 1 mark for correctly stating whether the two one-sided limits agree.

• 1 mark for concluding that the limit does or does not exist, based on the comparison of the one-sided limits.