AP Syllabus focus:

‘Develop and practice a decision process for limits that involves checking continuity, trying substitution, simplifying expressions, or switching to graphical and numerical approaches.’

A structured decision strategy helps analyze complex limits by organizing choices among substitution, simplification, continuity checks, and graphical or numerical methods when algebra alone cannot resolve behavior.

Building a Decision Strategy for Complicated Limit Problems

A reliable decision strategy for limits provides a consistent pathway for interpreting complex expressions and determining which analytical or representational tools will most effectively reveal a function’s nearby behavior.

Understanding the Purpose of a Decision Strategy

A decision strategy for limits is a systematic procedure that guides you through evaluating a limit when the method is not immediately obvious. It prevents wasted effort on ineffective techniques and ensures alignment with the syllabus priority of using continuity, substitution, simplification, and alternative representations strategically.

Step 1: Check Function Structure and Domain Behavior

Before attempting calculations, examine the structural type of the function—rational, radical, trigonometric, exponential, piecewise, or composite—because each structure suggests likely approaches.

Identify domain restrictions, especially points where denominators are zero or radicals require nonnegative arguments.

Determine whether the function is continuous at the point of interest, meaning its limit equals its function value.

Observe whether the expression resembles an indeterminate form (e.g., ), which signals the need for further algebraic work.

Step 2: Attempt Direct Substitution When Allowed

Direct substitution is the quickest strategy for continuous functions. When the inner components of a composite function are continuous at the point, substitution yields the true limit.

Continuity at a Point: A function is continuous at if exists, the limit as approaches exists, and the two are equal.

If substitution produces a valid numerical value, the limit is determined immediately. When substitution instead yields undefined or indeterminate expressions, the strategy must progress to algebraic methods.

Step 3: Simplify Algebraically to Resolve Indeterminate Forms

When substitution fails, algebraic manipulation becomes essential for constructing an equivalent expression that reveals the limit.

Factor common terms to cancel problematic components.

Rewrite rational expressions to expose cancelations.

Use algebraic identities to simplify trigonometric or radical expressions.

Apply conjugates to rationalize numerators or denominators involving square roots.

Reexpress piecewise functions in simplified form near the point of interest.

These steps aim to eliminate indeterminate forms and restore a version of the function compatible with substitution.

Step 4: Reevaluate Continuity After Simplification

Once the expression has been rewritten, reconsider whether the new form is continuous at the point in question.

If continuity now holds, substitution completes the evaluation.

If not, the structure may require a different strategy such as one-sided analysis or bounding techniques.

A limit does not require the original function to be defined at the point, so the simplified form often provides the necessary clarity.

Step 5: Use One-Sided Reasoning When Behavior Differs Across Approaches

Functions may behave differently when approached from the left and from the right, especially piecewise-defined or absolute value functions.

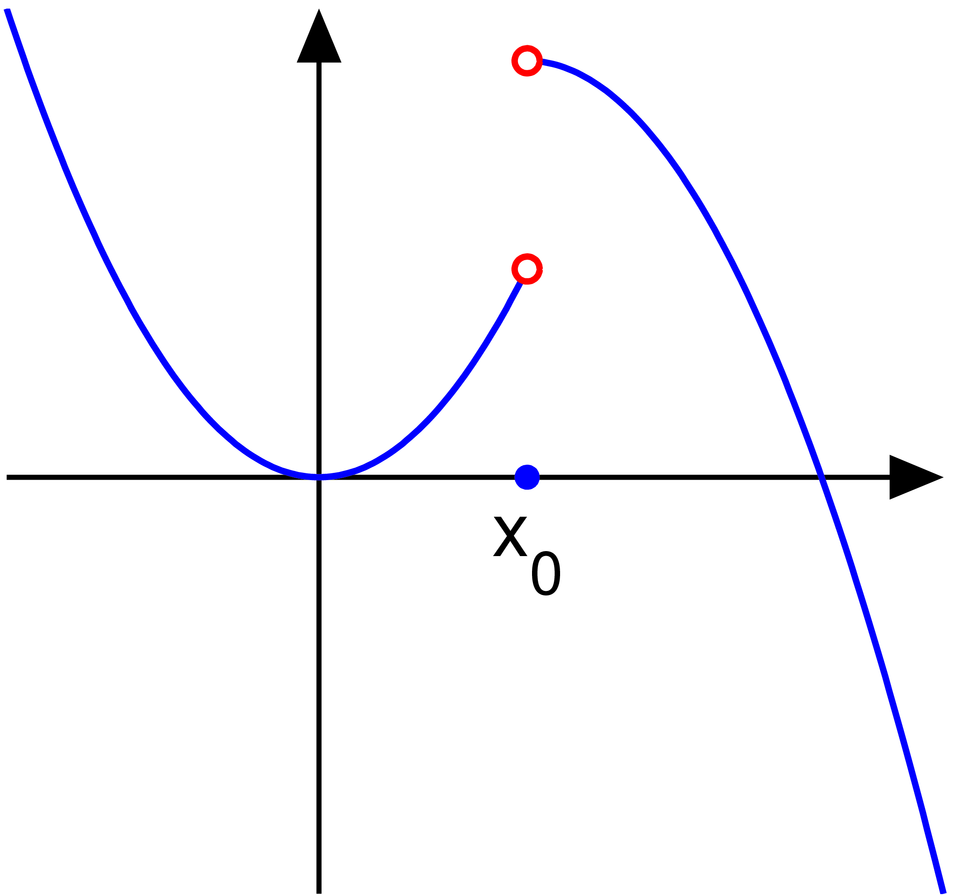

A graph illustrating unequal left-hand and right-hand limits at a jump discontinuity, emphasizing how differing approach values prevent the existence of a two-sided limit. Although the curve shapes include extra stylistic detail beyond the AP syllabus, the essential concept—the mismatch of one-sided limits—is clearly displayed. Source.

Evaluate left-hand and right-hand expressions separately.

Compare limits to determine whether a two-sided limit exists.

Note that disagreement between one-sided limits means the limit does not exist.

This reasoning is vital when discontinuities or sharp transitions influence the limit.

Step 6: Employ Graphical and Numerical Techniques When Algebra Is Insufficient

Certain expressions resist algebraic simplification or involve oscillatory, undefined, or highly complex behavior. In these situations, graphical or numerical methods offer insight into nearby values.

Graphs reveal trends, limit values, jumps, or unbounded behavior near the point.

Tables allow observation of values approaching the target from both sides.

Use these tools when the algebraic form obscures behavior or contains intricate combinations of functions.

Step 7: Incorporate Bounding or Squeeze-Based Ideas When Appropriate

When a function is difficult to analyze directly but can be constrained between two simpler functions with the same limit, bounding strategies provide a powerful alternative.

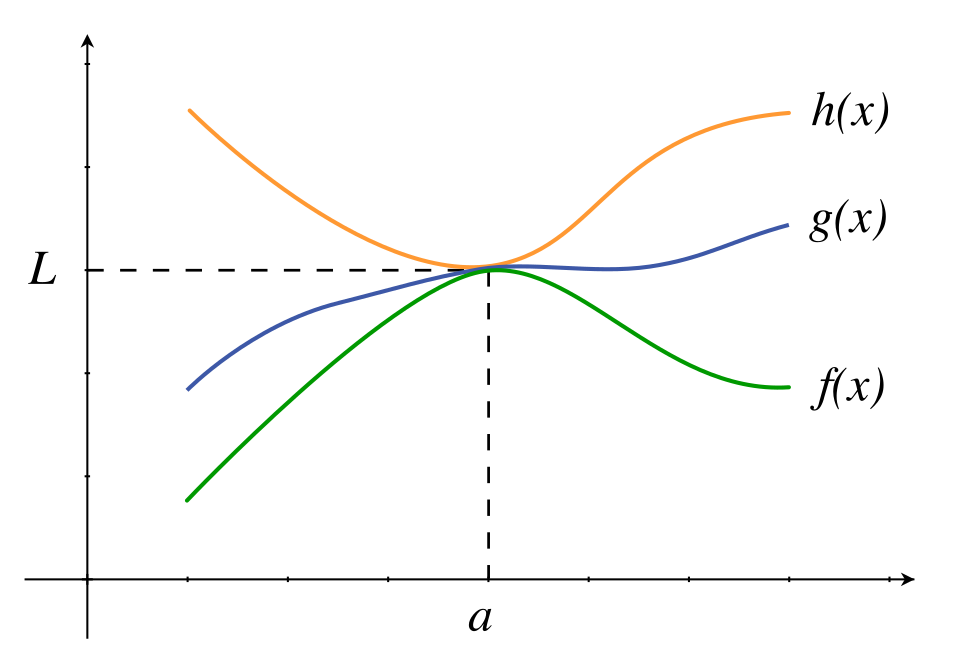

Squeeze Principle: If near , and , then .

These arguments appear most often in trigonometric or ratio-based limits that fluctuate yet remain confined.

A visual representation of the squeeze theorem, with a central function confined between two bounding functions that converge to the same limit. This supports the decision strategy step of using bounds when direct algebraic evaluation is difficult, even though the diagram includes a symbolic statement of the theorem beyond the informal emphasis of this subsubtopic. Source.

Step 8: Reassess and Iterate When Necessary

Difficult limit problems often require cycling through steps multiple times.

After applying a method, revisit earlier steps if the expression changes.

Recognize when a limit does not exist due to divergence, oscillation, or mismatched one-sided limits.

Maintain flexibility, shifting between algebraic and representational strategies for clarity.

Strategic Bullet-Point Summary for Decision Making

Start by examining structure and continuity.

Attempt direct substitution.

Simplify algebraically when substitution fails.

Reevaluate continuity and retry substitution.

Use one-sided limits for piecewise or asymmetric behavior.

Turn to graphs or tables for additional insight.

Apply bounding or squeezing when direct analysis is difficult.

Iterate the process as needed to reach a conclusion.

FAQ

Switch when repeated algebraic steps fail to remove an indeterminate form or when the expression becomes increasingly complicated without clarifying behaviour.

You should also switch if:

• The function is highly oscillatory near the point.

• The algebraic structure conceals behaviour that a graph or table can reveal quickly.

• One-sided behaviour appears asymmetric and needs visual confirmation.

Direct substitution often fails when the expression contains:

• Factors that may become zero simultaneously, producing a 0/0 form.

• Absolute values or piecewise components that create sharp transitions.

• Radicals nested within rational expressions, especially when numerator and denominator vanish together.

Recognising these patterns early prevents wasted steps and speeds up the decision process.

Look for structural cues:

• Piecewise definitions with different formulas on either side of a point.

• Absolute values or sign-dependent expressions.

• Graphs or tables showing abrupt changes close to the target x-value.

If any appear, examine left-hand and right-hand forms separately before committing to full algebraic manipulation.

Organise your work into short, labelled stages to avoid confusion:

• Step 1: Check continuity and attempt substitution.

• Step 2: Identify the form produced (e.g., indeterminate or undefined).

• Step 3: Choose an algebraic, graphical, or numerical method.

• Step 4: Re-test the limit after simplification.

This structure minimises errors and shows mathematical reasoning clearly.

Prioritise creating bounds that are simple, recognisable, and easy to evaluate.

Good bounding functions:

• Are naturally related to the behaviour of the original function.

• Share the same limiting value at the target point.

• Are easier to manipulate than the original function.

Avoid overly complex bounds, as they defeat the purpose of using a squeeze-based strategy.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

A function f is defined for all x close to 2. A student attempts to evaluate the limit of f(x) as x approaches 2 by direct substitution but obtains the indeterminate form 0/0.

(a) State the next step the student should take according to a strategic decision process for limits.

(b) Give one reason why this step is appropriate.

Question 1

(a) 1 mark: States an algebraic simplification step such as factorising, cancelling common factors, rationalising, or rewriting the expression.

(b) 1–2 marks: Gives a valid reason, such as removing the indeterminate form, creating an equivalent expression suitable for substitution, or clarifying behaviour near the point.

Total: 2–3 marks.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Consider the function g defined by

g(x) = (x + 3)(x − 5) / (x − 5) for x ≠ 5,

and g(5) = 4.

(a) Using an appropriate decision strategy, determine the limit of g(x) as x approaches 5.

(b) Explain why direct substitution into the original expression is not the best initial method.

(c) Describe how one-sided reasoning or graphical insight might support your conclusion.

(d) Based on your findings, comment on whether the function is continuous at x = 5.

Question 2

(a) 1–2 marks: Identifies the limit as 3 by cancelling the factor (x − 5) and evaluating the simplified form x + 3 at x = 5.

(b) 1 mark: Explains that substitution into the original expression produces 0/0, which is indeterminate, so simplification is needed.

(c) 1–2 marks: Describes that both one-sided values approach 3, or that a graph would show the function approaching a single height near x = 5.

(d) 1 mark: States that g is not continuous at x = 5 because the limit (3) does not equal the defined value g(5) = 4.

Total: 4–6 marks.