AP Syllabus focus:

‘Identify when a function is one-to-one or has a restricted domain so that an inverse exists, ensuring the derivative formula for the inverse function is valid.’

Understanding when an inverse function exists is essential for applying inverse derivative formulas correctly, requiring students to assess one-to-one behavior, domain restrictions, and conditions guaranteeing valid differentiation.

Inverses, One-to-One Functions, and Validity

A central idea in working with inverse functions is determining when a function actually has an inverse and when the derivative formula for the inverse may be validly applied. AP Calculus AB emphasizes recognizing structural conditions—especially one-to-one behavior and appropriate domain restrictions—to ensure inverse differentiation is mathematically justified.

One-to-One Functions and Their Importance

A function must be one-to-one in order for its inverse to exist. A function is one-to-one if it never takes the same output value for two different inputs. This condition guarantees that each output corresponds to exactly one input, allowing an inverse to reverse the original mapping.

One-to-One Function: A function in which different inputs always produce different outputs, allowing the function to have an inverse on its domain.

When studying differentiability, this property becomes essential because the inverse function must also behave predictably, especially when applying derivative rules. Without one-to-one behavior, the inverse relationship would be ambiguous and unusable in calculus.

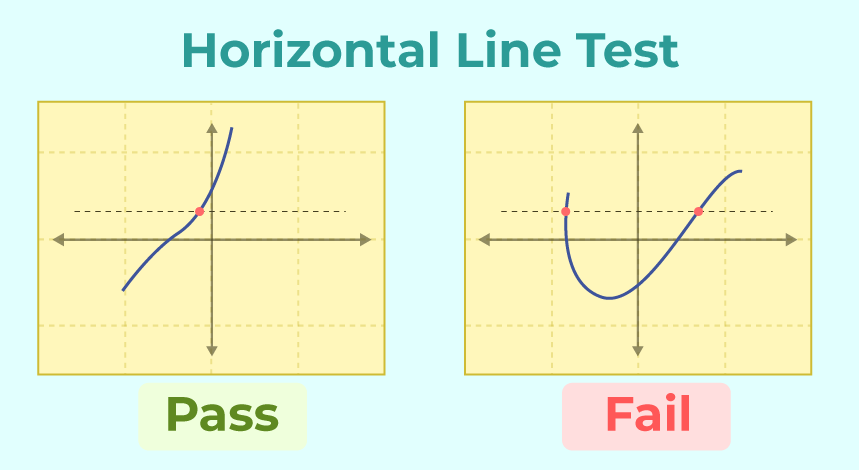

The Horizontal Line Test provides a visual method for determining one-to-one behavior:

• A function is one-to-one if and only if no horizontal line intersects its graph more than once.

• This test ensures that each -value corresponds to a single -value.

• It verifies invertibility without requiring algebraic manipulation.

This diagram shows two graphs used in the Horizontal Line Test: the left graph passes because each horizontal line intersects the curve at most once, while the right graph fails. The red points indicate repeated intersections, showing why the failing function is not one-to-one. This visual reinforces that only graphs passing the test can represent functions with valid inverses on their domains. Source.

Restricting Domains to Create Inverses

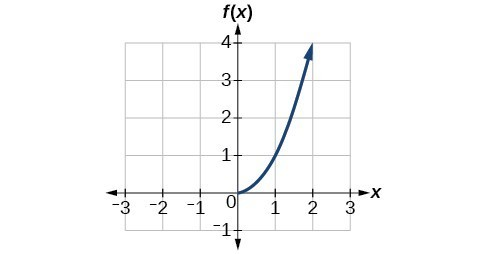

Many familiar functions, such as quadratic, trigonometric, or absolute value functions, are not naturally one-to-one on their full domains. However, they can become one-to-one when restricted to a domain where they behave monotonically.

This figure shows the right-hand branch of a quadratic defined only for , making the graph strictly increasing. This restriction ensures each horizontal line intersects the curve only once, allowing an inverse to exist. The image illustrates how restricting the domain of a familiar non-invertible function creates a valid inverse function. Source.

Domain Restriction: Limiting a function’s domain to a region on which it becomes one-to-one so that an inverse function may be defined.

For example, trigonometric inverses such as arcsin, arccos, and arctan exist only because their parent functions have been restricted to intervals on which they are one-to-one. Domain restrictions thus play a critical role in defining valid inverse functions and preparing them for differentiation.

After restricting a domain, students must consistently interpret all values through the lens of that restriction. This ensures that the inverse remains a function, not a multivalued relation.

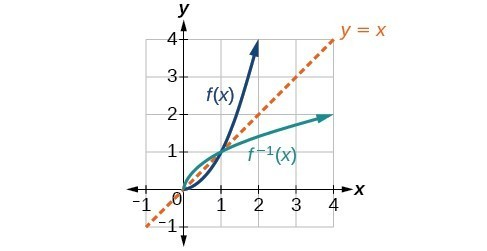

This image plots a restricted quadratic function and its inverse along with the line . The two graphs appear as reflections across the identity line, demonstrating how inverse functions relate geometrically. Although the specific functions go beyond the abstract requirement, they provide a clear visualization of invertibility and inverse structure. Source.

Validity Conditions for the Derivative of an Inverse

Once a function is known to be one-to-one and differentiable on its domain, the derivative of its inverse can be computed with a standard formula. However, this formula has essential validity conditions that must be met before use.

= Derivative of the original function, must be nonzero

For this relationship to hold, students must verify two critical requirements:

• The original function must be differentiable at the corresponding point.

• Its derivative must be nonzero, ensuring the inverse function is locally differentiable.

A zero derivative at the corresponding point would make the reciprocal undefined, invalidating the inverse derivative formula. Thus, checking is fundamental.

One full sentence is required here to comply with formatting rules and ensure separation between equation and further conceptual explanation.

Ensuring Proper Use of the Inverse Derivative Formula

To apply the inverse derivative formula correctly, students should follow a structured verification process:

• Check that the function is one-to-one on the interval being considered.

• Confirm that any necessary domain restrictions have been explicitly established.

• Identify the corresponding point by solving when evaluating .

• Verify that , ensuring the denominator in the formula is valid.

• Interpret the reciprocal relationship as reflecting the inverse nature between slopes of and .

Because AP Calculus AB problems may provide numerical tables or graphs instead of explicit formulas, students must also recognize invertibility visually and numerically. Using slope relationships directly from graphs allows for efficient reasoning without requiring symbolic manipulation.

Graphical and Conceptual Interpretation of Validity

Interpreting the derivative of an inverse function involves analyzing slopes, monotonicity, and local behavior. The slope of an inverse function at a point is the reciprocal of the slope of the original function at the corresponding point. When a graph shows a section where the slope of approaches zero, the slope of grows very large, highlighting why the original derivative must remain nonzero.

Additionally, students should view domain restrictions not as arbitrary constraints but as necessary structural adjustments that ensure monotonicity and allow the inverse relationship to function properly within calculus.

Therefore, understanding one-to-one behavior and validity conditions allows students to apply derivative formulas for inverse functions confidently, ensuring mathematical consistency across analytic, numerical, and graphical contexts.

FAQ

Check whether the function is strictly increasing or strictly decreasing on its domain.

If its derivative never changes sign and never equals zero across an interval, the function is monotonic and therefore one-to-one.

Alternatively, test injectivity directly: assume f(a) = f(b) and show that this implies a = b.

This method is especially helpful for piecewise or unfamiliar functions.

A function may look one-to-one over the region relevant to a problem but may not be one-to-one across its entire natural domain.

Restricting ensures the inverse is well-defined for all values in the range being used.

Domain restriction also prevents ambiguous inverse outputs when the original function eventually repeats values outside the region of interest.

The inverse still exists as a function, but its derivative does not exist at that point.

A zero derivative in the original function implies an infinite or undefined slope in the inverse.

This results in a sharp vertical tangent for the inverse curve.

Yes, provided each piece is chosen so the function overall is one-to-one.

To maintain invertibility:

• Each piece must connect without producing repeated output values.

• No two distinct inputs across the full domain may share the same output.

• If necessary, restrict the domain to a single monotonic piece.

The output of the inverse becomes the input where the original slope must be measured.

This ensures the reciprocal slope relationship applies at the correct corresponding points.

This correspondence aligns the geometry: each point on the inverse function reflects a point on the original curve across the line y = x.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

A function f is defined on an interval where it is strictly decreasing and differentiable. Explain why f has an inverse on this interval, and state the condition on f that guarantees the derivative of its inverse exists at a point.

Question 1

• 1 mark: States that f is one-to-one because it is strictly decreasing.

• 1 mark: Concludes that being one-to-one implies f has an inverse on the interval.

• 1 mark: States that the derivative of the inverse exists when f'(x) is non-zero at the corresponding point.

Total: 3 marks

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

A function g is known to be one-to-one on its domain. You are told that g(2) = 5 and g'(2) = -4.

(a) Explain why g has an inverse function.

(b) Use the relationship between a function and its inverse to find (g^{-1})'(5).

(c) Give a brief interpretation of your answer in part (b) in terms of slopes.

Question 2

(a)

• 1 mark: States that g is one-to-one, therefore an inverse exists.

(b)

• 1 mark: Identifies that the corresponding point on g is x = 2 because g(2) = 5.

• 1 mark: Applies the inverse derivative relationship correctly: (g^{-1})'(5) = 1 / g'(2).

• 1 mark: Substitutes g'(2) = -4 to obtain (g^{-1})'(5) = -1/4.

(c)

• 1 mark: Interprets the result as the slope of the inverse curve at the point where its output is 5 (or input 5), noting that it is the reciprocal of the slope of g at x = 2.

Total: 6 marks