AP Syllabus focus:

‘Solve related rates problems that involve similar triangles or trigonometric relationships, relating side lengths or angles and differentiating to connect their rates of change.’

Related rates problems involving similar triangles or trigonometric relationships connect changing geometric quantities through proportionality or angle-based formulas. These situations require interpreting how one changing measurement influences another.

Understanding Relationships in Similar-Triangle and Trigonometric Models

When two or more quantities vary with respect to time, identifying the geometric relationship between them is essential. Similar triangles and trigonometric ratios supply equations that reveal how these variables depend on each other, allowing differentiation with respect to time.

Recognizing Similar Triangles in Related Rates

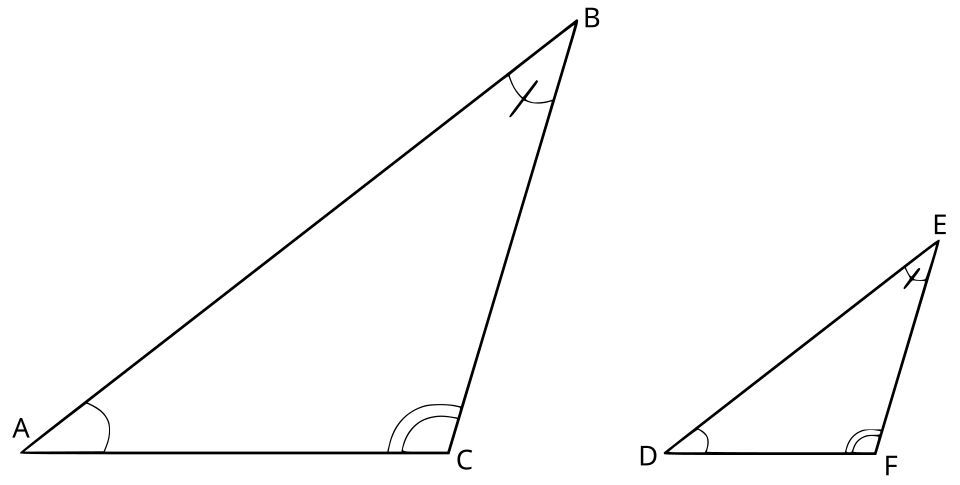

Similar triangles arise when two triangles share the same shape but differ in size.

This diagram shows two similar triangles with corresponding angles and sides marked to indicate equality. The matching angle arcs and side tick marks emphasize that the triangles share the same shape but differ in size, supporting proportional relationships. This visual underpins situations where changing side lengths are connected through similarity in related rates problems. Source.

Similar Triangles: Triangles with equal corresponding angles and proportional corresponding side lengths.

When similar triangles apply, one typically writes a ratio of corresponding sides and simplifies to form an equation involving only the quantities relevant to the related rate. This step is crucial because related rates problems require differentiating an equation that contains only variables whose rates matter at the instant described.

Using Proportional Relationships

Proportionality allows conversion of a geometric situation into an equation suitable for implicit differentiation. Before differentiating, it is often helpful to reduce ratios to simplify the final relationship. Ensuring proportional relationships are correct preserves the integrity of the calculus to follow.

= Variable side lengths that change with time

= Fixed or known corresponding side lengths

A proportional equation must be expressed in terms of variables whose rates of change are either known or sought. Eliminating unnecessary constants or substituting similar-triangle ratios strengthens clarity and accuracy.

A sentence here to maintain spacing between equation blocks.

Trigonometric Relationships in Changing-Angle Situations

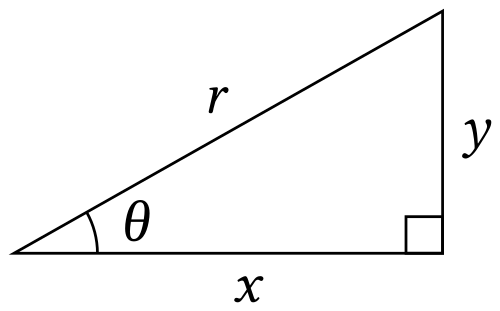

In some related rates problems, triangles are not similar in a proportional sense but still involve an angle that defines relationships between sides. Trigonometric functions allow modeling of these geometric dependencies when distances and angles vary over time.

This right-triangle diagram shows angle θ, hypotenuse r, adjacent side x, and opposite side y. These relationships form the basis of trigonometric ratios such as , which become time-dependent when the quantities change. The figure visually supports related rates setups involving changing angles or distances. Source.

Trigonometric Ratio: A function, such as sine, cosine, or tangent, defining a relationship between side lengths and angles of a right triangle.

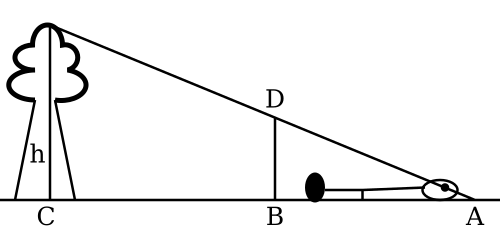

Common scenarios include objects moving toward or away from a point, rotating beams of light, or changing viewpoints.

This diagram models a right triangle formed by the height of a tree, the ground, and an observer’s line of sight. Although static, it demonstrates geometric relationships that become time-dependent in related rates problems. The same trigonometric structure applies when distances or angles change over time. Source.

Building a Trigonometric Equation for Differentiation

A trigonometric relationship is chosen based on known quantities and the variable whose rate is required. Students must ensure every variable in the equation represents a quantity changing with respect to time unless it is explicitly constant. After selecting the correct function, the equation is differentiated implicitly using the chain rule because every variable is a function of time.

= Angle changing with respect to time (radians)

= Side lengths changing with respect to time

Implicit differentiation of trigonometric expressions requires careful use of derivative formulas. Because the quantities depend on time, this process demands multiplying by derivatives such as , , and as appropriate.

A sentence to follow the equation block as required.

Differentiating Equations in Similar-Triangle and Trigonometric Contexts

Once an equation has been constructed from geometric reasoning, the next step is implicit differentiation with respect to time. Differentiating a proportion or trigonometric relationship introduces derivative terms corresponding to each variable involved. When working from a similar-triangle equation, one typically rewrites the relationship as a single expression rather than a ratio to avoid quotient-rule complications.

Applying the Chain Rule to Time-Dependent Variables

Because all relevant quantities depend on time, the chain rule ensures that derivatives reflect this dependence. Each derivative introduces a rate term, linking geometric relationships to temporal change. Accurate application of the chain rule is central to solving related rates problems in this subsubtopic.

Chain Rule: A differentiation rule stating that the derivative of a composite function requires multiplying by the derivative of the inner function.

In the context of related rates, the chain rule ensures that differentiating a variable such as x produces dx/dt, capturing how rapidly the quantity changes at the instant described.

Interpreting Rates Derived from Similar Triangles or Trigonometry

After differentiation and substitution, the resulting expression yields the desired rate. Correct interpretation requires identifying what is increasing or decreasing and expressing this in appropriate units tied to the physical or geometric scenario. Signs carry meaning: a negative rate may represent approaching movement, shrinking distance, or decreasing angle.

Ensuring the Equation Reflects the Geometry

The validity of a related rates solution depends on beginning with an accurate geometric model. Similar triangles must be confirmed before use, and trigonometric functions must reflect the correct relationships within the triangle. Careful diagram labeling and consistent variable definitions strengthen the reliability of the final rate obtained.

FAQ

If the two triangles in the scenario share angle–angle similarity and their side ratios remain fixed, similar triangles are appropriate. This often occurs in spotlight problems, shadow problems, or any situation where two triangles scale proportionally.

Use trigonometry instead when:

• Only one triangle is involved

• Angles vary over time

• A fixed-length side such as a hypotenuse is central to the model

The key is identifying whether proportionality or angle-based relationships best reflect the geometry.

Many errors come from failing to eliminate unnecessary variables before differentiating. Oversized ratios may introduce quotient rule complications that are avoidable.

Other frequent mistakes include:

• Assuming a side is constant when it actually changes over time

• Forgetting to apply the chain rule to each variable

• Mixing up corresponding sides when forming ratios

Accurate diagram labelling prevents most of these issues.

Angles often change at rates that depend on both horizontal and vertical distances, so understanding how an angle evolves is essential.

Angles may increase or decrease even if distances grow, depending on how the triangle reshapes. For example, a person moving away from a light source may experience a decreasing angle even while all distances increase.

Analysing the geometry helps predict the sign and magnitude of angular rates.

Simplification reduces algebraic complexity and makes implicit differentiation easier.

Useful strategies include:

• Rewriting fractions to avoid a quotient rule

• Selecting the trigonometric function that uses only relevant sides

• Replacing compound expressions with a single variable when geometry permits

Aim for the smallest number of variables while keeping the relationship accurate.

A clear diagram is the foundation of a correct model. Label all variables and keep track of which quantities depend on time.

Check the following:

• Are the correct sides paired in ratios?

• Does the triangle structure remain valid as motion occurs?

• Are any angles or sides actually constant when the problem states they change?

Verifying each assumption against the physical scenario improves both accuracy and interpretation.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

A vertical pole stands on level ground. A point on the ground is 12 metres from the base of the pole. A light shines from the top of the pole, forming an angle of elevation θ between the line of sight and the ground. At a certain instant, the height of the pole remains constant while the observer walks directly away from the pole at 1.2 metres per second.

Using the relationship tan(θ) = h / x, where h is the height of the pole and x is the horizontal distance, find dθ/dt at the instant the observer is 12 metres away.

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

• 1 mark: Correct substitution into tan(θ) = h / x and recognition that h is constant.

• 1 mark: Correct differentiation using the chain rule to obtain sec^2(θ) dθ/dt = –h / x^2 dx/dt.

• 1 mark: Correct evaluation of dθ/dt at x = 12 metres using dx/dt = 1.2 metres per second, with correct sign.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

A 5-metre ladder leans against a vertical wall. The foot of the ladder is sliding away from the wall along flat ground. Because the wall is smooth and vertical, the ladder, the wall, and the ground form a right-angled triangle.

The top of the ladder is sliding down the wall, and similar triangles show that the ratio between the vertical height of the ladder on the wall and the horizontal distance of its foot from the wall is the same at all times.

At one moment, the foot of the ladder is 3 metres from the wall and moving away at 0.4 metres per second.

(a) Using the similar-triangle relationship, write an equation relating the vertical height y to the horizontal distance x.

(b) Differentiate this equation with respect to time.

(c) Hence find dy/dt at the instant described, stating the sign of the answer and interpreting its meaning.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

(a)

• 1 mark: Correct use of similar triangles to state a proportional relationship, for example y = kx or x / y = constant, with k identified using the ladder length.

(b)

• 1 mark: Differentiation with respect to time performed correctly, showing application of the chain rule (e.g., dy/dt = k dx/dt if y = kx, or an equivalent form from the chosen relationship).

(c)

• 1 mark: Substitution of x = 3 metres and dx/dt = 0.4 metres per second into the differentiated equation.

• 1 mark: Correct calculation of dy/dt, including correct sign indicating downward movement.

• 1 mark: Clear interpretation that the top of the ladder is sliding down the wall at the calculated rate.