AP Syllabus focus:

‘Check that related rates answers are reasonable by comparing signs, magnitudes, and units with the situation described, and revising work if the result conflicts with the context.’

Straightforward related rates computations can mask subtle errors, so evaluating the reasonableness of solutions ensures alignment with a problem’s physical, geometric, or contextual constraints.

Checking Reasonableness of Related Rates Solutions

Understanding the Purpose of Reasonableness Checks

When a related rates problem yields a numerical rate, the value must make sense within the context. This subsubtopic emphasizes verifying that the sign, magnitude, and units of a calculated rate are consistent with the described situation. Students should learn to interpret whether an answer is physically possible, mathematically consistent, and contextually appropriate before accepting it.

Key Components of Reasonableness

1. Signs of Rates

The sign of a rate indicates the direction of change. A positive rate reflects increase, while a negative rate reflects decrease. Misinterpreting the sign often leads to conclusions that contradict the scenario. For example, if a quantity must be shrinking, a positive rate would signal an inconsistency that requires revisiting the prior steps.

Sign of a Rate: The positive or negative indicator showing whether a quantity is increasing or decreasing with respect to the independent variable.

A rate’s sign must agree with qualitative information given in the problem’s wording. If the context states that a measurement is getting smaller, the derivative describing its change must be negative.

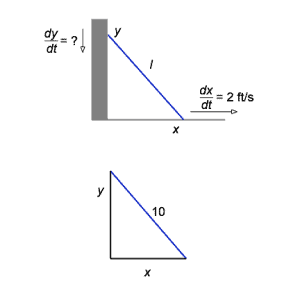

Diagram of a ladder leaning against a vertical wall, forming a right triangle with the ground. The horizontal distance xxx and vertical height yyy represent quantities changing over time, illustrating why one rate is positive while the other is negative. Some numerical labels extend slightly beyond this subsubtopic but serve to demonstrate sign interpretation in related rates contexts. Source.

2. Magnitude of Rates

The magnitude of a rate communicates how fast a quantity changes. Even if the sign is correct, an unrealistic magnitude suggests computational or conceptual mistakes. When evaluating reasonableness, compare the rate to typical scales in the problem. A very large or extremely small magnitude may signal a misapplied formula, incorrect substitution, or algebraic error.

Magnitude of a Rate: The absolute size of a rate of change, reflecting the speed of the change without regard to direction.

After determining the magnitude, consider whether the modeled physical system could plausibly change at such a speed given its constraints.

The Role of Units in Verification

Units serve as a consistency check, confirming that each step in a related rates solution aligns with the dimensions of the quantities involved. Unit mismatches often reveal differentiation errors or incorrect relationships between variables. Rates for related quantities must exhibit units that reflect how one measurement depends on another.

Dimensional Consistency: The requirement that the units of a computed rate correctly represent the dependent variable’s units divided by the independent variable’s units.

A rate should never contain units that do not match the problem’s structure; for example, mixing linear and area units without a geometric justification indicates an underlying mistake.

Connecting Rates to the Context

Contextual interpretation ties together signs, magnitudes, and units to ensure the final result reflects the described situation. This step requires rereading the problem and comparing the computed rate with the behavior expected at that specific instant. Because related rates problems involve dynamically changing quantities, verifying that the computed rate matches the direction and speed of change at the moment in question is essential.

Systematic Process for Assessing Reasonableness

1. Compare the Sign to the Described Behavior

• Determine whether the quantity should be increasing or decreasing.

• Ensure the computed derivative shares that direction.

• Reevaluate calculations if the sign disagrees with the scenario.

2. Evaluate the Magnitude Against Contextual Expectations

• Estimate typical measurement scales from the problem.

• Compare the computed rate with realistic physical or geometric constraints.

• Watch for magnitudes inconsistent with the system’s behavior.

3. Confirm Unit Consistency

• Verify that the final units match the dependent variable per unit of time or another independent variable.

• Check that all substitutions and differentiation steps preserve correct dimensional relationships.

• Identify whether any mismatch suggests misuse of a formula or misinterpretation of a variable.

Using Mathematical Structure to Detect Errors

The relationships between quantities in related rates problems arise from underlying geometric or physical principles. Because these relationships impose structural patterns, inconsistencies often appear when an answer violates the expected behavior of that structure. For example, if two linked quantities must move in opposite directions due to geometry, both rates cannot reasonably be positive. Recognizing expected structural relationships provides a powerful tool for validating solutions.

= Any dependent quantity with units appropriate to the context

= Time, typically in seconds, minutes, or hours

When interpreting this relationship, ensure the computed derivative accurately reflects how the quantity should behave at the instant of interest.

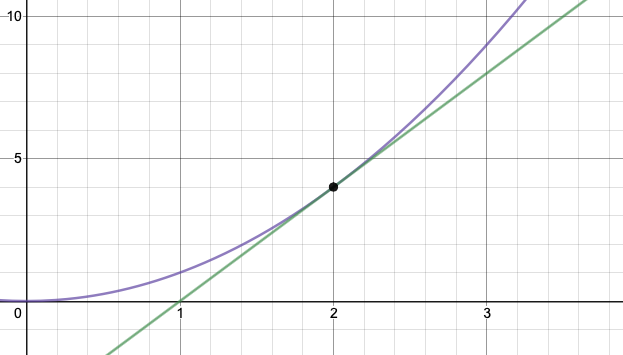

Graph of the parabola y=x2y = x^2y=x2 with a tangent line at (2,4)(2,4)(2,4), illustrating how a derivative represents instantaneous rate of change. The slope’s sign and steepness show how magnitude and direction can be judged for reasonableness. Although the function is not tied to a specific related rates scenario, it reinforces interpretation of in context. Source.

Revising Work When Results Are Unreasonable

If any component—sign, magnitude, or unit—fails the reasonableness check, reevaluating equations, differentiation steps, or substitutions is necessary. Common issues include misidentified variables, incorrect geometric relationships, or algebraic slips. The revision process reinforces the idea that related rates solutions must be judged not only by computation but also by interpretive coherence.

Incorporating Contextual Awareness Throughout

Maintaining contextual awareness ensures that each step of solving a related rates problem aligns with the situation’s physical meaning. This focus supports accurate interpretation of the final rate and reduces the likelihood of accepting results that contradict the scenario.

FAQ

A good starting point is to review the assumptions made before differentiating. Many unreasonable results arise because a relationship between variables was chosen too quickly or without fully reflecting the physical situation.

Check whether the quantities genuinely depend on one another in the way the equation suggests. If the structural relationship is wrong, even flawless differentiation will produce an unreasonable rate.

A sign may align with the context while the magnitude does not, because scale is often overlooked.

Common causes include:

• Using inconsistent units (for example, mixing metres and centimetres).

• Substituting extreme values accidentally.

• Applying a formula that magnifies small input changes.

Comparing the result to the approximate size of the object or situation usually reveals this mismatch.

Units act as a built-in diagnostic tool. If the derivative yields units that do not match the expected physical quantity, then somewhere along the line a step has violated dimensional consistency.

Unit checking is especially effective for detecting algebraic cancellations or substitutions that accidentally remove or introduce a dimension.

Exam markers expect logical justification, not perfect estimation. Your reasoning should show clear awareness of the physical or geometric limits of the context.

For example, explaining that a tank cannot fill at the stated rate because the number is far too large for its size will meet expectations even without numerical comparison.

When intuition suggests something is wrong, consider:

• Whether the model applies only at a single instant and not across the interval you have in mind.

• Whether external constraints (such as maximum heights or fixed lengths) limit the range of valid values.

• Re-checking whether the substituted numerical values correspond exactly to the instant described.

Suspicious results often arise from using the correct methods at the wrong moment in the scenario.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

A spherical balloon is being inflated, and at a certain instant its radius is increasing. A student calculates the rate of change of the balloon’s volume at that instant and obtains a negative value.

Explain why this result is not reasonable in the context of the situation.

Question 1

• 1 mark: States that a negative rate of change of volume is not reasonable because the balloon is being inflated.

• 1 mark: Explains that inflation means the volume must be increasing, so the rate must be positive.

• 1 mark: Suggests that a sign error or incorrect substitution likely occurred.

(Any 1–3 of the above for a maximum of 3 marks.)

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Water is being pumped into a cylindrical tank at a constant rate. At a particular moment, the depth of the water is increasing slowly. A student constructs the related rates model and correctly differentiates the volume formula. After substituting values, the student concludes that the depth of the water is rising at 15 metres per minute.

(a) Explain why the magnitude of this result is not reasonable.

(b) State one further method the student could use to check whether the calculated rate is consistent with the situation.

(c) Give one step the student should take if the rate is found to be unreasonable.

Question 2

(a)

• 1 mark: States that 15 metres per minute is unrealistically large for the depth of water in a typical tank.

• 1 mark: Compares the magnitude to a contextual expectation (for example, the tank cannot fill that fast given its dimensions).

(b)

• 1 mark: Mentions checking units for consistency.

• 1 mark: Mentions comparing the sign of the rate with the expected behaviour.

• 1 mark: Mentions verifying the geometric relationship or re-examining the model.

(Any one valid method for 1 mark.)

(c)

• 1 mark: States that the student should revisit the differentiation, substitutions, or geometric relationships to identify the source of error.

(Total: 4–6 marks depending on detail and correctness.)