AP Syllabus focus:

‘Use the derivative and a point on the curve to find the slope and equation of the tangent line, preparing it for use as a local linear approximation.’

Finding the equation of a tangent line is essential for understanding how derivatives describe local behavior, enabling precise linear approximations and meaningful interpretations of differentiable functions.

The Purpose of a Tangent Line

A tangent line provides the best linear prediction of a function’s value near a specific point. Because a differentiable function is locally linear, its behavior close to a chosen input can be modeled using a straight line. The tangent line captures both the instantaneous rate of change and the function’s value at a chosen point, making it a foundational tool for approximation and interpretation.

Understanding the Slope of a Tangent Line

The slope of the tangent line at a point is given by the function’s derivative at that point. When we compute a derivative, we are measuring how the dependent variable changes relative to the independent variable at a specific location on the curve.

Derivative: The instantaneous rate of change of a function with respect to its input, giving the slope of the tangent line at a point.

This slope tells us whether the function is increasing or decreasing and how steeply it behaves near the point.

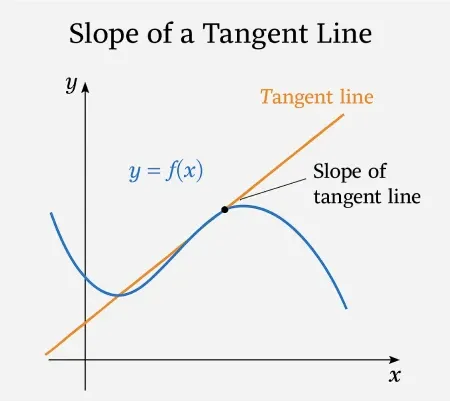

This graph shows a differentiable function together with its tangent line at a point. The tangent line has the same slope as the curve at that point, illustrating the instantaneous rate of change. The labeled slope arrow reinforces that the derivative value represents the slope of this line. Source.

Before determining the full tangent line, it is necessary to know both the slope and a corresponding point on the curve. These two pieces of information uniquely determine a line.

General Form of a Tangent Line Equation

Once the slope and point are known, we use the point–slope form of a line. This structure emphasizes that the tangent line is anchored to the function at the chosen input value. In AP Calculus AB, this format is both standard and essential, especially when preparing linearizations for later use.

= Slope of the tangent line at

= Input value where the tangent line touches the curve

= Function value at the point of tangency

This representation ensures that the tangent line passes exactly through and has slope .

Essential Steps for Constructing a Tangent Line

Constructing a tangent line follows a clear and repeatable process. AP Calculus AB emphasizes understanding why each step matters as well as performing the computation accurately.

Step-by-Step Structure

Students should follow this sequence to ensure they identify all necessary components:

Identify the point of tangency.

Confirm the input value and compute to anchor the line.Differentiate the function.

Compute using standard derivative rules.Evaluate the derivative at the point.

Substitute to obtain the slope .Apply the point–slope form of a line.

Construct the tangent equation using known values.Rewrite if needed for interpretation.

Slope–intercept form may assist with graphical understanding, though point–slope form is typically preferred in calculus contexts.

Each step reinforces the connection between algebraic structure and the geometric meaning of derivatives.

Why Tangent Lines Matter in Context

A tangent line is more than an abstract construction; it conveys how a function behaves at a specific instant. Because the tangent line shares the function’s slope at one point, it indicates whether change is occurring rapidly, slowly, positively, or negatively. In applied settings, the tangent line can represent:

A momentary trend in physical motion

A brief snapshot of population change

An economic model’s behavior at a specific production level

Although this subsubtopic does not delve into linearization, the tangent line is the basis for such approximations.

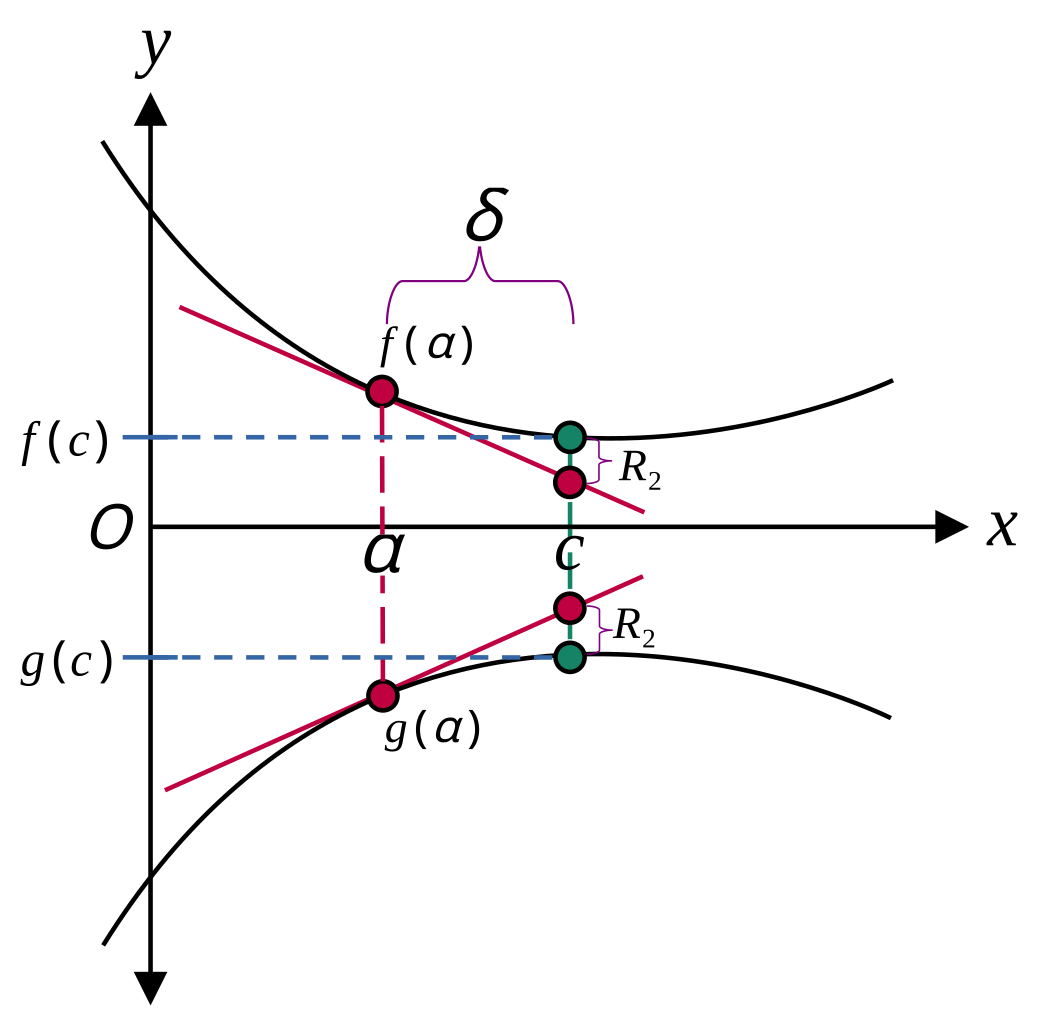

The figure shows two functions, and , each with a tangent line drawn at the shared input , along with nearby points whose values are approximated by the tangent lines. It illustrates how a tangent line provides a local linear model for estimating function values near a point. The inclusion of symbols like , , and goes beyond AP requirements but merely marks distances and approximation errors. Source.

Understanding its form is fundamental for later topics such as estimating values, analyzing concavity effects on predictions, and interpreting real-world behaviors.

Notation and Interpretation

The tangent line’s slope is often written as or , both of which communicate an instantaneous rate of change. Students should interpret this slope in terms of:

What quantity is changing

The variable with respect to which it changes

The units involved

Even though formal unit interpretation belongs to other subsubtopics, recognizing that the tangent line conveys a measurable rate strengthens comprehension of its purpose.

Communicating Tangent Line Results

A complete tangent line description must clearly identify:

The function being considered

The point of tangency

The derivative calculation

The final line written in a clear algebraic form

Clarity of communication is essential, especially when tangent lines are used to support arguments about function behavior or approximate values.

This structure ensures the tangent line serves as an accurate, meaningful linear model tied directly to the function’s instantaneous behavior.

FAQ

A tangent line touches the curve at exactly one point locally and matches the curve’s instantaneous rate of change at that point.

A secant line intersects the curve at two distinct points and represents the average rate of change over an interval rather than at a single location.

Geometrically, as the two points of the secant line move closer together, the secant line approaches the tangent line. This limiting behaviour forms the conceptual basis of the derivative.

The point–slope form directly incorporates the two quantities calculus provides: the point of tangency and the derivative value at that point.

It avoids unnecessary algebraic rearrangement and highlights the dependence of the tangent line on the slope at a specific input. This makes it especially useful for local linear approximation and further calculus operations.

Yes. Although a tangent line touches the curve at a single point locally, it may cross the graph elsewhere.

This often occurs when the curve bends away from the tangent line rapidly, such as with inflection points or steep concavity changes. The tangent line still accurately represents the curve’s behaviour extremely close to the point of tangency, even if it intersects the graph again further away.

Inspect the immediate direction of the curve at the point of tangency.

• The slope is positive if the curve is rising from left to right.

• The slope is negative if the curve is falling from left to right.

• The slope is zero if the curve appears momentarily flat, typically at a turning point.

This visual assessment becomes more reliable with practice and is a key skill for graphical interpretation.

A tangent line in calculus reflects the limiting behaviour of secant lines as the interval shrinks to zero. This limit only exists when the function has a well-defined instantaneous rate of change.

At corners, cusps, or vertical tangents, the derivative fails to exist or is undefined, meaning a single, unique tangent line cannot represent local behaviour. Differentiability ensures smoothness that supports a stable tangent direction.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

A function h is differentiable and satisfies h(2) = 5 and h’(2) = -3.

(a) Write the equation of the tangent line to the curve y = h(x) at x = 2.

(b) State what the value h’(2) = -3 indicates about the behaviour of h at x = 2.

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

(a)

• 1 mark: Correct substitution of point and gradient into point–slope form (for example, y - 5 = -3(x - 2)).

• 1 mark: Correct simplified tangent line equation (for example, y = -3x + 11).

(b)

• 1 mark: Correct interpretation that the function is decreasing at x = 2, with a rate of change of -3 units of y per unit of x.

Total: 3 marks

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

A differentiable function f has the following properties:

• f(1) = 4

• The derivative f’(x) is given by f’(x) = x² - 2x + 1

(a) Find the slope of the tangent line to y = f(x) at x = 1.

(b) Hence write the equation of the tangent line at x = 1.

(c) Explain how this tangent line can be used to approximate the value of f(1.1).

(You are NOT required to compute the approximation.)

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

(a)

• 1 mark: Substitution of x = 1 into derivative.

• 1 mark: Correct slope value (f’(1) = 0).

(b)

• 1 mark: Use of point–slope form with f(1) = 4 and gradient 0.

• 1 mark: Correct tangent line equation (y = 4).

(c)

• 1 mark: Statement that the tangent line provides a local linear approximation of f near x = 1.

• 1 mark: Explanation that f(1.1) can be estimated by substituting x = 1.1 into the tangent line equation, because differentiable functions are locally linear.

Total: 6 marks