AP Syllabus focus:

‘Use the tangent line, or linearization, to approximate function values near the point of tangency when the exact value is difficult or impossible to compute directly.’

Linearization provides a powerful way to approximate complex function values using the tangent line, allowing students to estimate outputs quickly when exact computation is inefficient.

Understanding Linearization in Context

The idea of linearization centers on the fact that differentiable functions behave almost like straight lines when viewed very close to a specific point. This local straight-line behavior enables us to replace a curved function with its tangent line, which is easier to compute and manipulate.

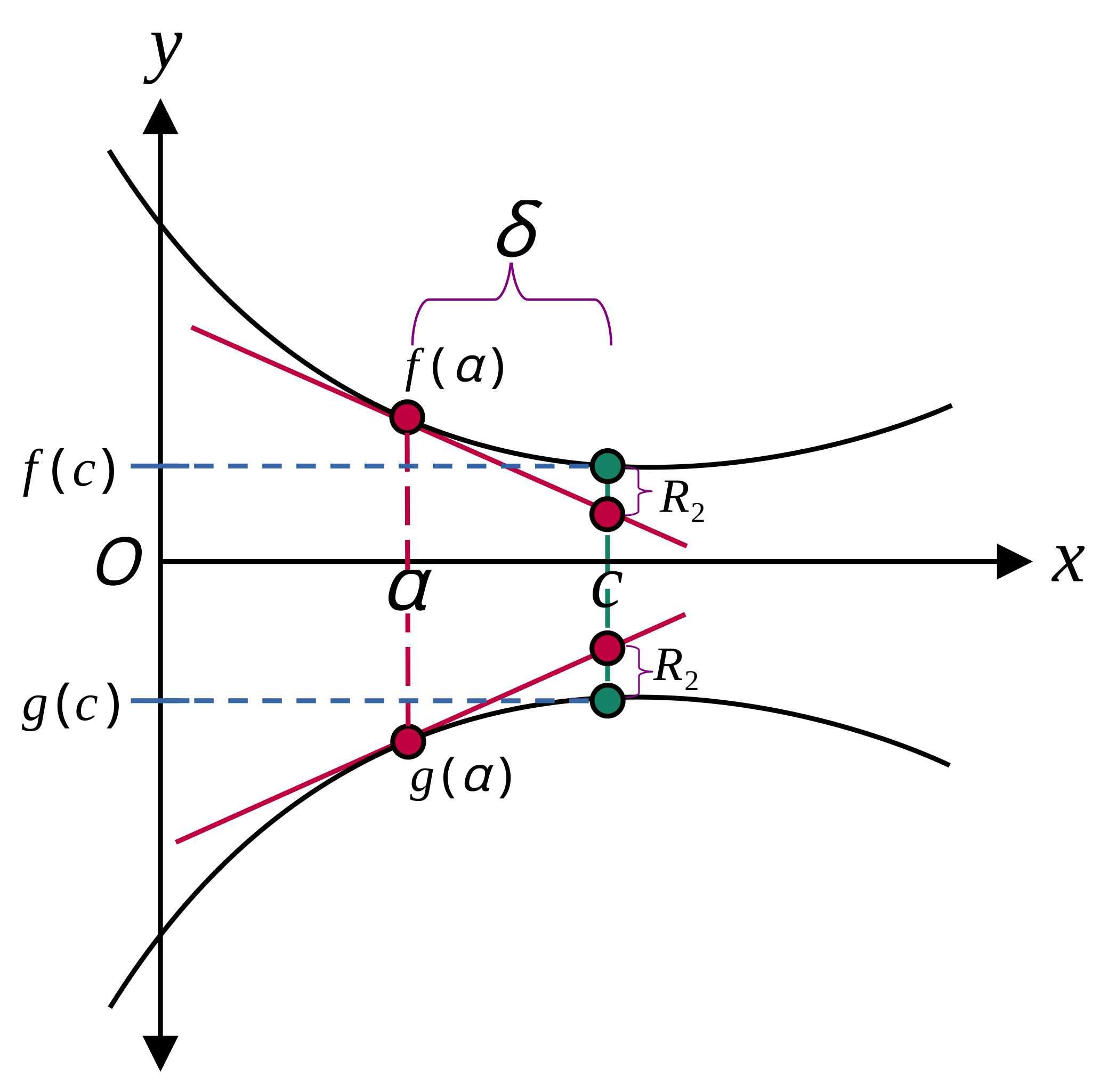

This diagram shows two differentiable curves alongside their tangent lines, illustrating how each tangent line provides a local linear approximation. Near the point of tangency, the line and curve nearly overlap, demonstrating the principle of linearization. Source.

When studying linearization, the essential task is to connect the behavior of a function to the behavior of its tangent line. The tangent line acts as a local linear model, capturing the function’s instantaneous rate of change and using that information to estimate new values.

Constructing a Linearization

To create a linearization, one identifies a function that is differentiable at a chosen point and computes both the function value and its derivative at that point. These quantities define the tangent line, which becomes the approximating linear function. Because the tangent line shares the same slope and value as the function at that point, the approximation is typically strongest for values of the input variable very close to the chosen point.

Key Components of a Tangent Line Approximation

A tangent line approximation depends on two essential pieces of information: the value of the function at the point of tangency and the value of the derivative at that same point. These establish the height and steepness of the tangent line. After determining these values, one forms an expression that mimics the nearby behavior of the original function.

= Function value at the chosen point (units of output)

= Instantaneous rate of change at the point (units of output per unit of input)

= Input variable

= Point of tangency

This expression models the function’s behavior around . After forming the linearization, students can substitute a nearby input into to approximate the function’s value.

Why Linearization Works

Because differentiable functions are locally linear, their tangent lines provide close approximations when zoomed in sufficiently near the point of tangency. This closeness occurs because the derivative captures how the function changes instantly at that point. When is close to , the difference between the actual curve and the tangent line becomes small enough that the linear model offers a robust estimate of the true value.

Interpreting Linearization Results

Interpreting the meaning of a linear approximation requires relating the tangent line values back to the context of the function. Since the linearization reflects how the function behaves around a particular input, the result represents an estimate of the original quantity at a nearby point. This estimate should always be read with attention to the function’s context, noting what is being approximated and the relevant units.

When using linearization, it is essential to consider whether the tangent line lies above or below the actual function near the point of tangency. This depends on the function’s concavity, which indicates whether the approximation might slightly overestimate or underestimate the true value. Although determining concavity formally belongs to another subtopic, understanding that curvature affects accuracy helps students evaluate their approximations thoughtfully.

Process for Using Linearization to Approximate Values

Students can rely on the following structured approach:

Identify the function and select the point where the value and derivative can be easily computed.

Evaluate the function at to determine .

Differentiate the function and compute the derivative value .

Construct the linearization using the expression .

Substitute the nearby input into the linearization to approximate the function’s value.

Interpret the result in context, ensuring that units and meaning align with the original function.

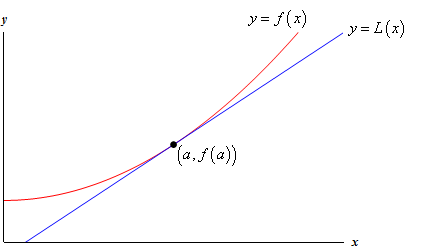

This graph depicts the function together with its tangent line at , illustrating how a linearization estimates nearby function values. Close to the point of tangency, the line and curve align closely, demonstrating accuracy; farther away, the approximation becomes less reliable. The specificity of the example exceeds general syllabus requirements but clearly shows the behavior of linear approximations. Source.

Approaching linearization with this sequential process helps ensure clarity, precision, and strong alignment with the AP Calculus AB expectations.

FAQ

There is no fixed numerical threshold, because reliability depends on how quickly the function curves away from its tangent line.

A function with gentle curvature allows accurate approximations over a wider interval, while a highly curved function restricts accuracy to values extremely close to the chosen point.

In practice, students look for small deviations from the expansion point, often choosing values within a narrow neighbourhood where the graph appears almost straight.

The derivative provides the instantaneous rate of change, which sets the precise slope of the tangent line. Without this slope, the tangent line would not match the direction of the function at the chosen point.

This ensures that the linear model behaves like the function at that exact moment, making it the best possible straight-line approximation locally.

A secant line uses two points on the curve, producing an average rate of change rather than an instantaneous one.

The tangent line, formed from a derivative at a single point, aligns perfectly with the curve's direction at that point.

As a result, linearisation is more accurate near the point of tangency, whereas secant-line estimates may drift away from the curve even very close to the chosen points.

Functions with sharp curvature or rapidly changing gradients often yield weak approximations, even within small intervals. Examples include:

• Functions with inflection points extremely close to the point of tangency

• Functions where the magnitude of the second derivative is large

• Oscillatory functions whose direction changes quickly

These characteristics cause the tangent line to diverge more rapidly from the actual curve.

Yes. Linearisation can provide insight into how a small change in input affects the output, helping predict qualitative trends in nearby behaviour.

It can also offer rough error estimates, because the discrepancy between the linear model and the function is influenced by curvature.

However, any such interpretations remain local and lose validity as the point of evaluation moves farther from the expansion point.

Practice Questions

A differentiable function f has f(2) = 5 and f'(2) = -3.

Use linearisation at x = 2 to approximate the value of f(1.8).

(1–3 marks)

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

• Correct use of linearisation formula: L(x) = f(2) + f'(2)(x − 2). (1 mark)

• Substitution of x = 1.8 and correct working:

L(1.8) = 5 + (-3)(1.8 − 2). (1 mark)

• Correct final answer: 5.6. (1 mark)

A function g is differentiable for all real numbers, and it is known that g(4) = 10 and g'(4) = 2.

(a) Write down the linearisation L(x) of g at x = 4.

(b) Use L(x) to approximate g(4.3).

(c) State one reason why this linear approximation may not be accurate if x is far from 4.

(4–6 marks)

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

(a) Linearisation written correctly:

L(x) = g(4) + g'(4)(x − 4). (1 mark)

(b) Correct substitution: L(4.3) = 10 + 2(4.3 − 4). (1 mark)

• Correct evaluation of expression: L(4.3) = 10.6. (1 mark)

(c) Appropriate reason, such as:

• The approximation becomes less accurate because the function may curve away from its tangent line as you move further from x = 4. (1 mark)

Additional accuracy or clarity in reasoning. (1 mark)

Total: 6 marks