AP Syllabus focus:

‘Given a graph of f, we can sketch f′ by estimating slopes: where f has positive, negative, or zero slope, f′ is above, below, or on the x-axis, respectively.’

This subsubtopic explains how to interpret a graph of a function and translate its visual slope behavior into a clear and accurate sketch of its derivative.

Understanding the Goal

Sketching f′ from a graph of f means converting visual information about how steeply and in what direction the graph rises or falls into a new graph that represents the instantaneous rate of change. Because the derivative measures slope, the process relies on observing where the original function increases, decreases, or levels off. The AP syllabus emphasizes deciding where the derivative is positive, negative, or zero by analyzing the slope of the tangent line drawn to the graph of f.

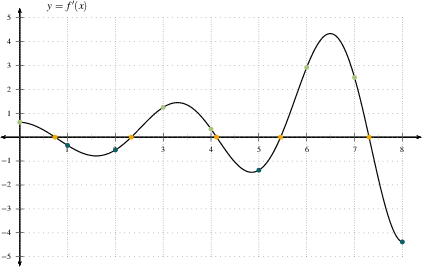

Graph of the derivative plotted on its own axes, with colored points marking selected derivative values. Heights of these points correspond to the slopes of tangent lines on the original graph at the same -values. This image includes specific numeric derivative values, slightly extending beyond the qualitative discussion but remaining aligned with AP Calculus AB expectations. Source.

Interpreting Slope from a Graph of f

When you look at a graph of f, you typically do not compute anything numerically. Instead, you visually assess slope behavior.

Key slope observations

Positive slope → the graph of f rises from left to right.

Negative slope → the graph of f falls from left to right.

Zero slope → the graph of f is momentarily flat, as at a horizontal tangent.

Steeper slope → the derivative magnitude is larger, whether positive or negative.

Gentle slope → the derivative magnitude is small.

These observations guide the placement of points and the overall shape of the derivative graph.

The Meaning of Instantaneous Rate of Change

The instantaneous rate of change refers to the slope of the tangent line to the graph at a point.

Instantaneous Rate of Change: The slope of the tangent line to the graph of a function at a specific point, represented by its derivative f′(x).

The derivative function encodes these slopes, so each x-value from the original graph corresponds to a y-value on the derivative graph representing the slope at that input.

Identifying Where f′ Is Zero

Horizontal tangents of f are essential markers. Any point where the original graph “levels off” corresponds to a point where the derivative crosses or touches the x-axis. These x-values often occur at peaks, valleys, or points of inflection, but the derivative only cares that the slope is zero.

Indicators of zero slope

Tops of smooth hills

Bottoms of smooth valleys

Places where the function transitions from rising to falling or vice versa

Points where the graph flattens even without forming a maximum or minimum

These points become the x-intercepts of f′.

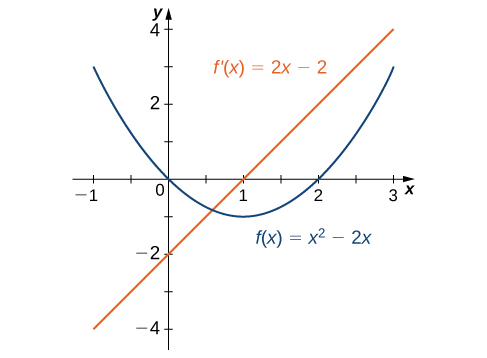

Graph of a parabola labeled together with its derivative line , illustrating that the vertex of aligns with the x-intercept of . The horizontal tangent at the vertex corresponds exactly to where . The image also labels explicit formulas, adding algebraic detail while remaining appropriate for AP Calculus AB. Source.

Determining Where f′ Is Positive or Negative

After locating where f′ equals zero, determine the sign of the derivative on each interval formed by those points.

Rules for deciding sign

f is increasing → f′(x) > 0 → plot derivative points above the x-axis.

f is decreasing → f′(x) < 0 → plot derivative points below the x-axis.

These sign decisions stem directly from how the slope of the tangent line behaves.

Using Relative Steepness to Estimate Magnitude

While the AP syllabus emphasizes sign, magnitude remains important for a faithful sketch. A steeper section of f corresponds to larger absolute values on the derivative graph.

Comparing steepness visually

If f rises gently, f′ should lie just slightly above the x-axis.

If f rises sharply, f′ should be noticeably higher.

If f descends steeply, f′ must fall farther below the x-axis.

If f becomes less steep, the derivative moves closer to the axis.

These magnitude estimates help ensure that the derivative graph is not merely qualitatively correct but also structurally accurate.

Locating Undefined or Non-Differentiable Points

Sharp corners, cusps, or vertical tangents in f indicate that the derivative does not exist at those points. These features appear on the derivative graph as breaks, gaps, or points not defined, depending on how the sketch is formatted.

Non-Differentiable Point: A point where the derivative does not exist, often due to a corner, cusp, discontinuity, or vertical tangent in the original function.

It is important that the derivative graph accurately reflects such undefined behavior rather than implying a smooth connection.

A normal sentence between definition and equation blocks clarifies that these non-differentiable locations must be represented explicitly so students do not confuse them with zero-derivative locations.

Building the Sketch of f′ Step-by-Step

To translate the graph of f into the graph of f′, follow a clear, structured process:

Process for Sketching the Derivative

Identify all horizontal tangents of f and mark their x-values.

Place points on the derivative graph at y = 0 for each x-value where f has zero slope.

Determine the sign of f′ on each interval between these points by checking whether f is rising or falling.

Estimate the steepness of f to determine how far above or below the x-axis the derivative should lie.

Mark non-differentiable points by leaving open circles or breaks in the derivative sketch.

Connect the points smoothly, keeping in mind that the derivative graph itself may curve differently from f.

This process ensures a derivative graph that respects the function’s geometric behavior and communicates the slope information visually and accurately.

Connecting Shape Patterns Between f and f′

Although this subsubtopic focuses on slopes rather than concavity, certain patterns emerge naturally:

When the slope of f increases steadily, f′ itself rises.

When the slope decreases, f′ falls.

When the slope changes gradually, f′ varies smoothly.

When slope changes abruptly, f′ may show sharp turns or discontinuities.

Recognizing these patterns supports trustworthy graphing and reinforces the conceptual meaning of the derivative as a function measuring instantaneous rate of change.

FAQ

Your sketch does not need to reflect exact numerical values, but it must correctly represent the signs of f′ and the relative steepness of f.

Focus on:

• Where f′ is positive, negative, or zero

• Where f becomes steeper or flatter

• How changes in slope affect the overall shape of f′

A derivative sketch that preserves these qualitative features is considered accurate, even if the underlying graph of f is only approximate.

Even if the slope appears close to zero, it is rarely exactly zero unless the curve genuinely levels out.

In such cases:

• Sketch f′ close to the horizontal axis but not necessarily touching it

• Use noticeable horizontal tangents only when the graph truly flattens

• Maintain the trend of increasing or decreasing slope even in nearly flat regions

This avoids incorrectly adding extra zeroes of f′.

Curvature does not directly affect f′, but it influences how slope changes from point to point.

For quick curvature changes:

• Expect f′ to change direction more sharply

• Watch for places where slope increases or decreases rapidly

• Ensure that the derivative graph mirrors the speed of slope variation, not the curvature itself

Remember, slope changes drive the derivative, not how “bent” the curve looks.

If the graph has a cusp, corner, or vertical tangent, f′ does not exist at that point.

To represent this correctly:

• Leave a gap or open circle on the sketch of f′ at the corresponding x-value

• Do not force the derivative graph to connect smoothly

• Show the left-hand and right-hand behaviour approaching that point, if visible

This conveys the non-differentiability clearly and accurately.

Rely on comparative steepness rather than exact measurements.

Look for:

• Sections where f rises or falls very gently — f′ should be close to the x-axis

• Steep portions — f′ should be noticeably far from the axis

• Changes in steepness — f′ should trend upward or downward smoothly to reflect this

You are assessing relative slope, not precise numeric gradients.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

The graph of a differentiable function f is shown. At x = 2, the graph has a horizontal tangent, and on the interval 2 < x < 4 the graph is decreasing.

Based only on this information, state the sign of f′(2) and the sign of f′(x) for 2 < x < 4, with a brief justification.

Question 1 (3 marks total)

• 1 mark: Correctly states f′(2) = 0 (horizontal tangent).

• 1 mark: Correctly states that f′(x) is negative for 2 < x < 4.

• 1 mark: Provides a correct justification, for example: “The function is decreasing on this interval, so its derivative is negative.”

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

The graph of a function f is provided. The graph rises steeply for x < –1, flattens to form a local maximum at x = –1, then decreases until x = 1 where it has a local minimum, before increasing again for x > 1.

Using this graphical information:

(a) Sketch the general shape of the derivative f′, labelling the approximate x-values where f′ is zero.

(b) Explain how the steepness of f on each interval affects the relative height of f′.

(c) Identify any intervals where the magnitude of f′ is large and justify your choice using features from the graph of f.

Question 2 (6 marks total)

(a) 3 marks

• 1 mark: Identifies that f′ = 0 at x = –1 and x = 1 (local maximum and minimum).

• 1 mark: Shows f′ positive for x < –1 and for x > 1 (where f is increasing).

• 1 mark: Shows f′ negative on the interval –1 < x < 1 (where f is decreasing).

(b) 2 marks

• 1 mark: States that steeper sections of f correspond to larger magnitudes of f′.

• 1 mark: Correctly links relative steepness of f to the approximate height of the plotted f′ curve.

(c) 1 mark

• 1 mark: Identifies correct intervals where f is steep (for example, x < –1 or x > 1) and justifies that these produce large positive or negative values of f′ because the slope of f is large in magnitude.