AP Syllabus focus:

‘Use known differentiation rules to find antiderivatives, reversing power, exponential, and trigonometric derivative formulas to obtain basic integration rules.’

Reversing basic derivative rules allows us to construct antiderivatives by recognizing familiar patterns from differentiation. This process forms the foundation of many fundamental integration techniques.

Reversing Derivative Rules for Antiderivatives

Understanding how to “undo” differentiation relies on identifying which differentiation rule originally generated a given function. When students see a function that resembles a derivative they already know, they apply the corresponding reversed rule to obtain its family of antiderivatives. An antiderivative is a function whose derivative returns the original function.

Antiderivative: A function whose derivative equals a given function, forming part of a family of functions differing by a constant.

Recognizing these patterns streamlines integration and avoids unnecessary manipulation. The strategy rests on three main rule families emphasized in the syllabus: the power rule, exponential rule, and trigonometric rules.

Power Rule Reversal

The reversed power rule handles the majority of polynomial and algebraic expressions seen in AP Calculus AB. The rule applies to all powers except the case where the exponent equals negative one. When a term resembles for some real number , the antiderivative increases the exponent by one and divides by the new exponent.

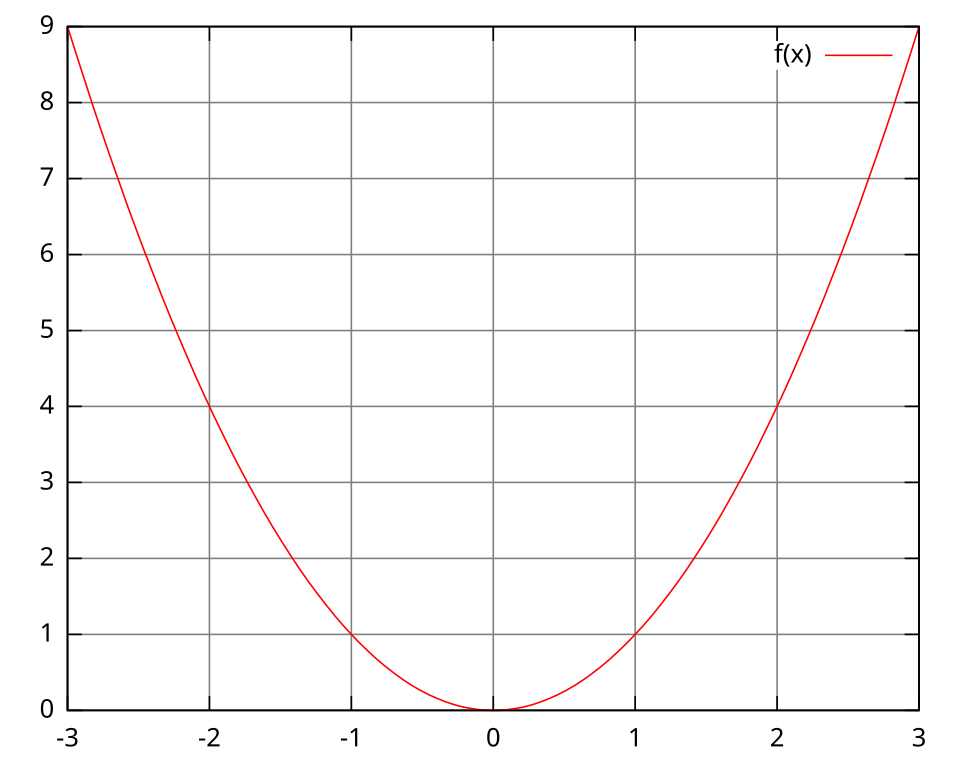

Graph of the square function illustrating a typical power-function curve used when applying the reversed power rule. The labeled axes emphasize how each input maps to its squared output. No extra content beyond visualizing the power rule is included. Source.

= Any real number except

This rule provides the foundation for integrating polynomials term by term. It also highlights the importance of noticing when an integrand does not match this form, such as with the special case , which instead reverses the derivative of . A brief awareness of when the power rule does not apply ensures students choose the appropriate reversed rule instead.

Exponential Rule Reversal

Exponential functions often exhibit simple derivative patterns. Reversing these patterns allows students to integrate functions involving bases such as . The most critical is the natural exponential function, since its derivative reproduces itself. Thus the antiderivative of must also reproduce this form in reverse.

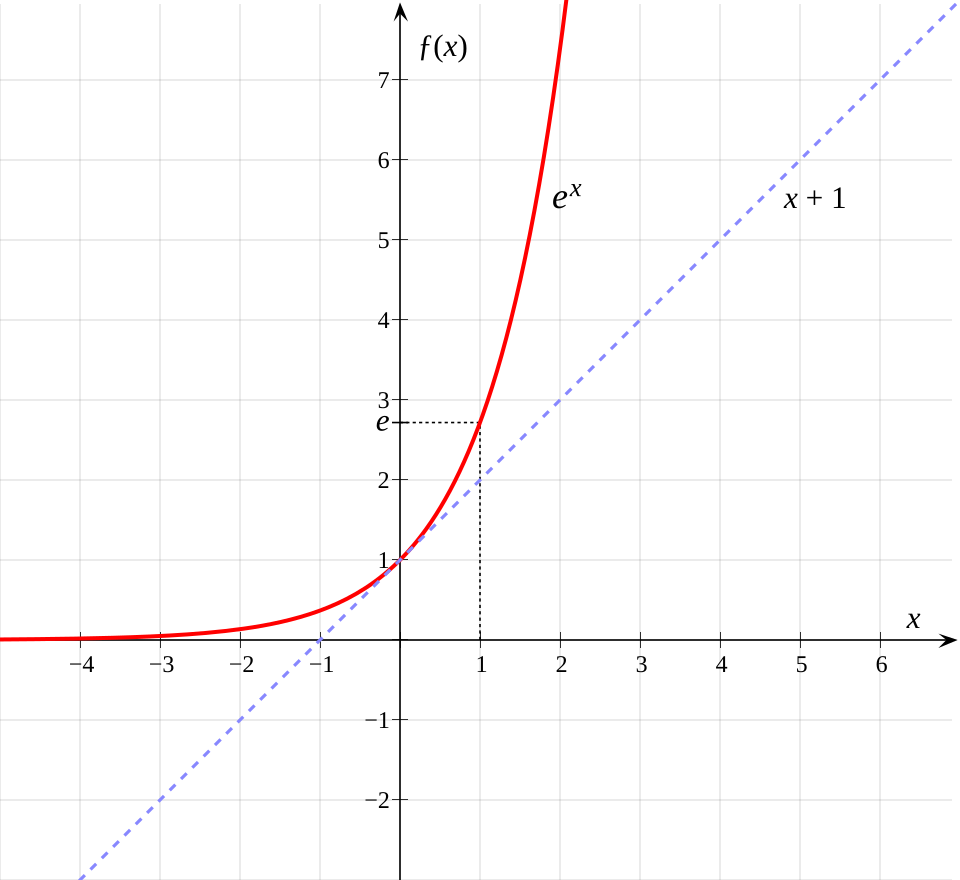

Graph of with its tangent line at , illustrating that the slope of the curve equals its own value at every point. This highlights why reversing the derivative rule yields . The tangent line is an extra detail depicting derivative behavior beyond the syllabus requirement. Source.

While basic AP Calculus AB emphasizes , students also encounter functions of the form where is a positive constant not equal to 1. Recognizing the derivative pattern for enables its reverse.

= Positive constant,

Integrating exponentials using reversed derivative rules reinforces the relationship between exponential growth models and their accumulated-change interpretations.

Trigonometric Rule Reversal

Reversing fundamental trigonometric derivative rules forms a central part of early integration skills. Students must recall which functions differentiate to produce the basic trigonometric outputs found in integrands. Key relationships include the derivatives of sine, cosine, and tangent, along with their reversed rules for antiderivatives. Before applying these reversed rules, students must recognize that trigonometric integration often depends on memorizing foundational derivative relationships so they can be undone quickly and accurately.

A sentence must appear between equation blocks to maintain clarity and spacing.

Students should also remember reversed rules for derivatives involving secant and tangent. These arise from commonly used differentiation relationships.

A short explanatory sentence here improves readability and meets spacing requirements.

Together, these reversed rules allow students to integrate many elementary trigonometric expressions without further manipulation.

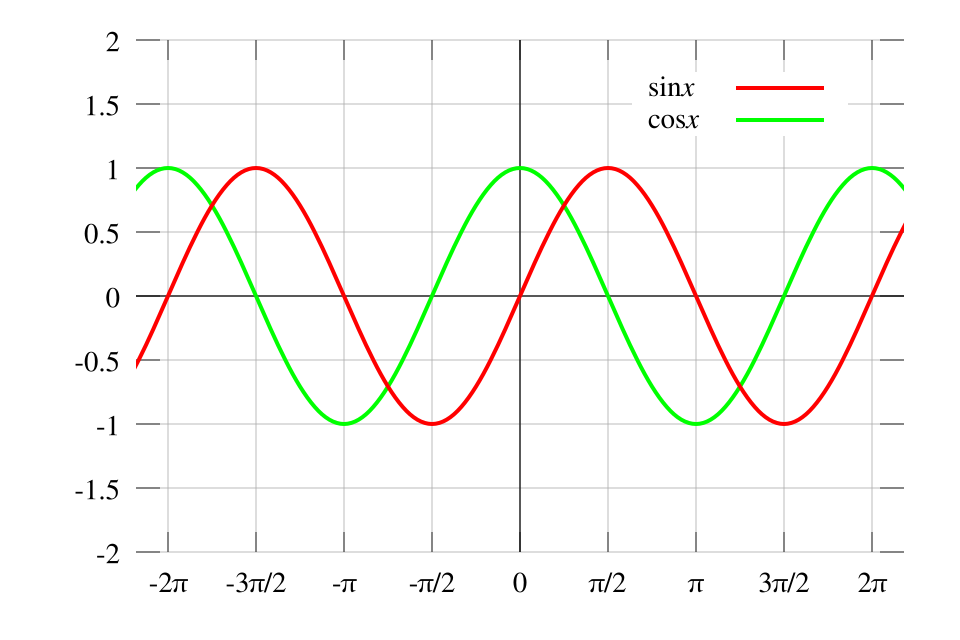

Plot of (red) and (green), showing their periodic behavior and phase shift. The markings in multiples of clarify the repeating nature of these functions. The full multi-period view extends slightly beyond the syllabus but helps reinforce the derivative–antiderivative relationship. Source.

Strategic Recognition of Derivative Patterns

Identifying the correct reversed rule relies on constant comparison to known derivative forms. Students should become comfortable asking themselves which differentiation rule produced the integrand they see. Useful strategies include:

Scan for recognizable forms such as , , , or .

Check for constants multiplying or accompanying familiar expressions. When necessary, factor constants out before applying a reversed rule.

Remember the constant of integration , which reflects the family of all possible antiderivatives.

Differentiate your answer mentally to confirm it reproduces the given integrand.

Reversing derivative rules forms a core integration method across the course. Students who master these patterns improve both accuracy and efficiency as they progress to substitution and more advanced techniques.

FAQ

A function may not match any familiar derivative pattern, even after factoring out constants.

Common indicators include:

• Expressions involving products of unrelated functions, such as x multiplied by a trigonometric function.

• Functions containing compositions that suggest substitution instead.

• Rational expressions that do not resemble simple power functions.

If none of the derivative rules for power, exponential, or basic trigonometric functions fit, a different integration technique is likely required.

The expression 1/x is equivalent to x raised to the power −1. The reversed power rule requires the exponent not to be −1 because increasing −1 by one gives 0, and dividing by 0 is undefined.

Instead, 1/x is the derivative of the natural logarithm function, so its antiderivative is the logarithmic form, which falls outside the strict reversal of the power rule.

A constant multiple never changes the underlying derivative pattern, so it can simply be factored out before integrating.

For example:

• If the integrand resembles a known derivative form multiplied by a constant, pull the constant outside.

• Apply the reversed rule to the remaining function.

This keeps the process systematic and reduces errors.

Differentiating the proposed antiderivative is the most reliable method.

A quick mental checklist includes:

• Does differentiating the candidate function reproduce the original integrand?

• Do signs match, especially for trigonometric functions?

• Have constant multiples been handled correctly?

If any part fails, reconsider which derivative pattern the integrand most closely resembles.

Several core trigonometric derivatives include negative signs, and forgetting these when reversing the rule leads to incorrect antiderivatives.

Key situations where errors occur:

• The derivative of cos x is −sin x, so reversing sin x requires careful attention.

• The derivative of tan x and sec x involve compound expressions, making their reversed rules appear less intuitive.

Checking each step against known derivative relationships helps prevent mistakes.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Find the general antiderivative of the function f(x) = 5x⁴ − 3 sin x.

Question 1 (3 marks)

• Correct use of the reversed power rule to integrate 5x⁴ (1 mark)

• Correct use of reversed trigonometric rule to integrate −3 sin x (1 mark)

• Correct inclusion of + C (1 mark)

Final answer: x⁵ − 3(−cos x) + C = x⁵ + 3cos x + C

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

A function h is defined on the real numbers and its derivative is given by

h'(x) = 2e^x + 4cos x − 12x².

(a) Find the general antiderivative h(x).

(b) Given that h(0) = 10, determine the specific value of the constant of integration and write the particular solution for h(x).

Question 2 (6 marks)

(a)

• Correct antiderivative of 2e^x (1 mark)

• Correct antiderivative of 4cos x (1 mark)

• Correct antiderivative of −12x² (1 mark)

• Proper inclusion of the constant of integration + C (1 mark)

General antiderivative: h(x) = 2e^x + 4sin x − 4x³ + C

(b)

• Correct substitution of x = 0 and h(0) = 10 to form an equation for C (1 mark)

• Correct solution for C and final particular solution (1 mark)

Since h(0) = 2e^0 + 4sin 0 − 4(0)³ + C = 2 + 0 + 0 + C = 10,

C = 8.

Particular solution: h(x) = 2e^x + 4sin x − 4x³ + 8