AP Syllabus focus:

‘Explain the role of the constant of integration C in representing families of antiderivative functions that differ by a vertical shift.’

AP Calculus AB students must understand how the constant of integration shapes entire families of antiderivatives, revealing how multiple valid functions can share the same derivative and differ only by vertical displacement.

The Role of the Constant of Integration

When integrating a function to find an antiderivative, students often encounter the appearance of + C, a term representing an unlimited family of possible functions. This constant is essential because differentiation eliminates all constant terms, meaning many distinct functions can share the same derivative. The constant of integration ensures that antidifferentiation accounts for every such possibility and expresses the complete set of functions whose slopes match the original rate of change.

Why the Constant of Integration Exists

The appearance of the constant of integration comes directly from the fact that differentiation is not a reversible process in a one-to-one sense. Since any constant disappears under differentiation, antidifferentiation must reintroduce the full range of those constants to capture all valid solutions. This concept guarantees that every antiderivative is included and avoids suggesting that only a single original function is possible.

Constant of Integration: The arbitrary constant C added to an antiderivative to represent all functions that share the same derivative and differ by vertical translation.

Understanding this idea links integration to families of curves, each representing a different but equally legitimate solution to an indefinite integral.

Families of Curves Generated by + C

Each value of C corresponds to a different member of a family of antiderivatives, all sharing the same shape but located at different vertical positions. The slopes of these curves are identical at every point because they come from the same underlying derivative function. What changes from one member of the family to another is only the vertical shift, reflecting the chosen value of C.

Interpreting Vertical Shifts

Because the derivative measures rate of change rather than absolute height, shifting a curve vertically does not alter its derivative. This means every antiderivative of a given derivative function must take the form:

= Antiderivative (units depend on context)

= One chosen antiderivative of the function

= Constant determining vertical shift

This expression shows how all possible antiderivatives relate to one another through vertical translation. Any specific context or initial condition selects exactly one curve from the family.

A sentence explaining the geometric meaning demonstrates how vertical shifts preserve shape while distinguishing individual solutions.

Graphically, the constant of integration creates a family of curves obtained by shifting a single antiderivative graph up or down.

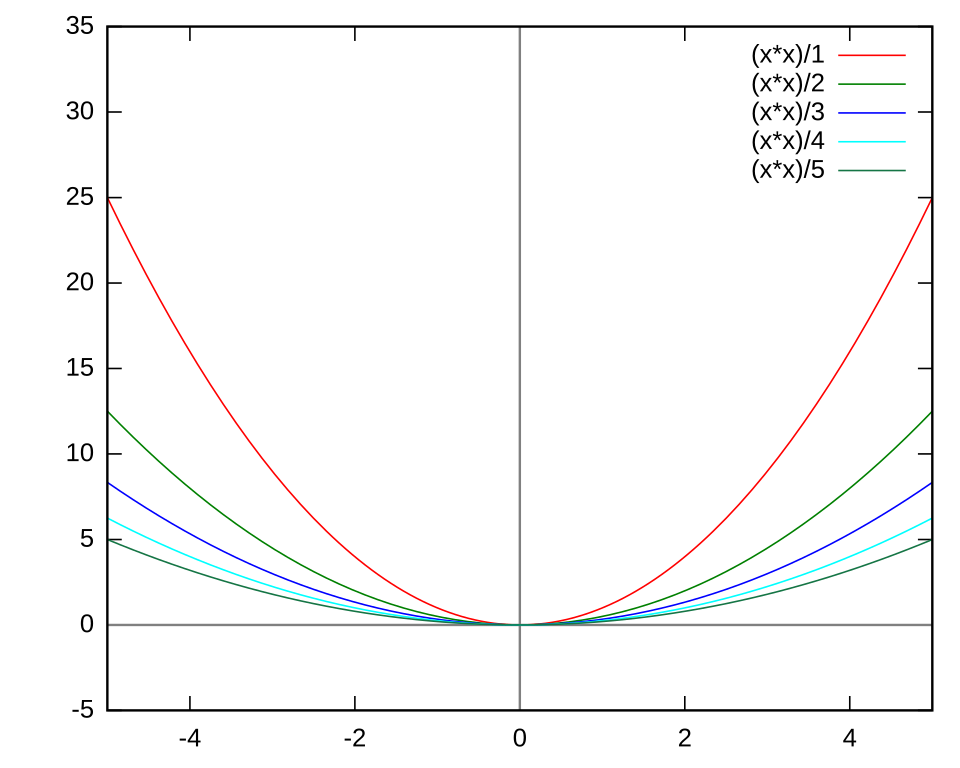

A family of parabolic graphs illustrates how a single functional shape can be repeated with different constants to form a family of curves. In an antiderivative context, shifts each curve vertically, producing many possible solutions with the same derivative. This image includes no extra concepts beyond the parameter-controlled family of functions. Source.

How Initial Conditions Determine C

While C is arbitrary when writing a general antiderivative, real-world contexts or initial-value information impose constraints that determine a specific value. In such cases, the constant of integration becomes calculable. Until such information is provided, students should always include + C to acknowledge the entire family of solutions.

Visualizing Families of Antiderivatives

When examining a family of curves generated by an indefinite integral, the curves appear as parallel or vertically translated copies of one another. They never intersect unless the constant changes correspondingly. Each curve maintains identical concavity and local behavior, because the second derivative of every member of the family is also the same. The only distinguishing feature is their position along the vertical axis, reinforcing the concept that C controls vertical displacement but does not affect any derivative-based characteristics.

An initial condition like F(x₀) = y₀ selects exactly one curve from the family, turning the general antiderivative with +C into a single particular solution.

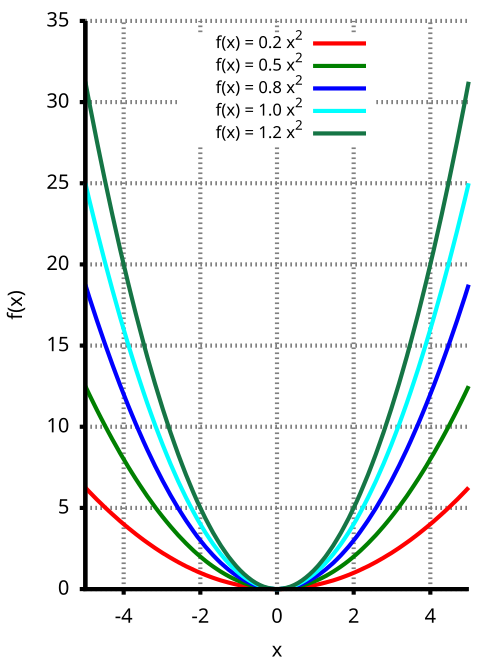

This graph shows a family of parabolas generated by varying a parameter. In the context of antiderivatives, each curve corresponds to a different constant of integration, while an initial condition selects just one curve. The broader theory of parameterized curve families appears in advanced mathematics, but only the vertical-shift idea is needed here. Source.

Importance in Mathematical Modeling

Many physical or applied problems depend on interpreting how accumulated quantities behave. Since integration often reconstructs total amounts from rates, the constant of integration can represent an unknown starting value, baseline level, or initial condition that must be determined externally. Whether describing position from velocity, volume from flow rate, or charge from current, the unspecified constant corresponds to real quantities that can be fixed only through contextual information.

Avoiding Common Errors with the Constant of Integration

Students must avoid omitting + C when writing general antiderivatives, as doing so incorrectly implies that there is a single solution rather than a family. Additional guidelines include:

Include + C for every indefinite integral, regardless of complexity.

Do not include + C in definite integrals, since the evaluation process cancels the constant automatically.

Recognize that the constant affects only vertical placement, not slope, curvature, or any derivative-based behavior.

Remember that different constants generate entirely different functions, even though they share identical derivatives.

One key insight is that the constant of integration is not a minor bookkeeping detail but a structural component of general antiderivatives.

Relationship to the Indefinite Integral Symbol

The notation ∫ f(x) dx represents all antiderivatives of f(x), not a single curve. The presence of C in the result communicates that this notation refers to a family of functions. Without the constant, the meaning of the indefinite integral would be incomplete and misleading.

Conceptual Summary of Families of Curves

The family-of-curves idea emphasizes that antidifferentiation produces not one function but infinitely many, all vertically shifted versions of a particular antiderivative. The constant of integration functions as a parameter that indexes these curves, with each choice of C selecting one specific member. Students should view the indefinite integral as a generator of function families, where C ensures completeness and aligns integration concepts with the geometric language of vertical translations.

FAQ

Only one constant is needed because differentiation removes only constant (zero-degree) terms, not higher-degree or variable terms.

If multiple constants were added, they would simply combine into a single constant. Any expression like C1 + C2 + C3 can be rewritten as one constant, keeping the family of antiderivatives both complete and simple.

Although usually written as a number, the constant can represent any fixed quantity determined by context.

For example:

• An unknown initial amount in a modelling scenario

• A reference height, baseline value, or offset

• Any constant determined by initial conditions

Its key property is that it does not depend on the variable of integration.

The constant does not alter the derivative, so the rate of change, curvature, turning points, and concavity remain identical for all curves.

However, the constant determines:

• Where specific features (such as intercepts) occur

• The vertical placement of all critical and inflection points

• Which curve is relevant in an applied setting with known starting values

When calculating definite integrals, any constant added to the antiderivative cancels out in the subtraction F(b) − F(a).

This means the definite integral depends only on the difference between two antiderivative values, not their absolute vertical positions. As a result, including the constant makes no numerical difference.

Initial conditions anchor the otherwise floating family of antiderivatives to a specific starting value.

Common examples include:

• A known initial displacement in motion problems

• A baseline population in growth models

• A starting temperature, charge, or volume

Substituting the given value into the general antiderivative yields the unique constant linked to that real-world situation.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

The derivative of a function F is given by F′(x) = 3x².

(a) Write down the most general form of F(x).

(b) Explain in one sentence what the constant in your answer represents.

Question 1

(a) 2 marks

• F(x) = x³ + C (1 mark for correct antiderivative, 1 mark for including + C).

(b) 1 mark

• States that the constant represents the vertical shift or the family of functions that all share the same derivative (1 mark).

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

A function G is defined as an antiderivative of g(x) = 2x – 4.

(a) Find the general expression for G(x).

(b) Given that G(1) = 10, determine the particular form of G(x).

(c) State clearly the role that the constant of integration plays in identifying the correct antiderivative in this context.

Question 2

(a) 2 marks

• Correct antiderivative: x² – 4x + C (1 mark for integrating 2x, 1 mark for integrating –4 and including + C).

(b) 2 marks

• Substitutes x = 1 into the general form and solves for C:

1 – 4 + C = 10 → C = 13 (1 mark for correct substitution, 1 mark for correct value).

(c) 1–2 marks

• Explains that the constant of integration represents all possible vertical shifts of the antiderivative (1 mark).

• States that the initial condition G(1) = 10 selects the unique member of this family (1 mark).