AP Syllabus focus:

‘Recognize that many functions do not have simple closed-form antiderivatives, requiring numerical methods or series representations instead.’

Many commonly used functions lack elementary antiderivatives, meaning they cannot be expressed using standard functions. Understanding this limitation guides appropriate integration strategies and strengthens conceptual fluency.

Understanding Functions Without Elementary Antiderivatives

Some integrands cannot be antidifferentiated using standard rules, substitutions, or algebraic techniques. These integrals appear frequently in calculus, physics, biology, and engineering, so recognizing them is essential for deciding when to apply alternative strategies such as numerical approximation, series expansion, or defining new special functions.

When we say a function has no elementary antiderivative, we mean that no finite combination of algebraic operations and elementary functions—polynomials, exponentials, logarithms, trigonometric and inverse trigonometric functions—can produce an antiderivative for that function.

Elementary Antiderivative: An antiderivative expressible using a finite combination of elementary functions such as polynomials, exponentials, logarithms, trigonometric functions, and their inverses.

This limitation does not mean the integral cannot be evaluated or approximated; rather, it cannot be written in a simple closed form. This distinction is a central idea in this subsubtopic and shapes how integrals involving such functions are handled in practice.

Recognizing When No Elementary Antiderivative Exists

Students should learn to recognize broad categories of functions whose antiderivatives do not simplify to known formulas. Although AP Calculus AB does not require proof of non-existence, developing intuition about common examples supports effective problem-solving.

Typical functions without elementary antiderivatives include:

e^(x²) and related exponential compositions.

(sin x) / x and other ratio functions that do not simplify under substitution.

ln(ln x) and deeply nested compositions.

1 / ln x and logarithmic reciprocals that defy substitution-based simplification.

√(1 + x³) and certain radicals involving higher-degree polynomials.

These forms resist standard antidifferentiation strategies because substitutions lead to expressions equally complex, and algebraic manipulation does not reduce the integrand to known integrable forms.

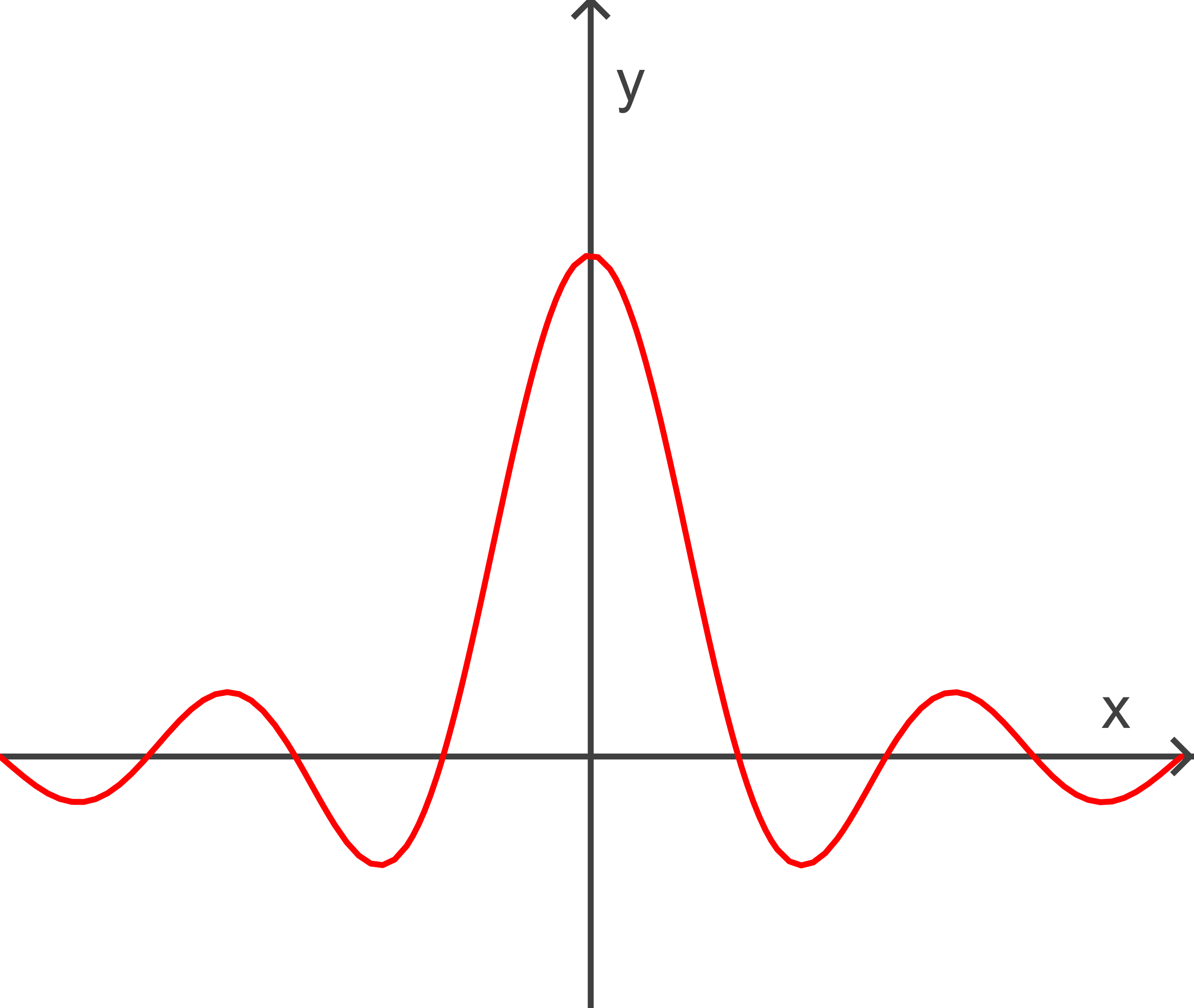

Graph of the function f(x) = (sin x)/x, a classic example whose antiderivative has no elementary closed form. The oscillatory behavior illustrates how the function behaves for large values of x. The extended domain shown includes more detail than required for AP Calculus AB but remains helpful for intuition. Source.

A key expectation for AP students is not memorizing specific exceptions but instead recognizing situations where typical techniques fail, signaling that an elementary antiderivative is unlikely to exist.

Why Some Functions Lack Elementary Antiderivatives

At a conceptual level, the set of elementary functions is limited, while compositions and products of functions form an extremely broad category. Many natural functions—especially those arising from oscillatory, exponential, or layered growth processes—produce integrands outside the scope of standard antidifferentiation tools.

This idea aligns with a major theme in the AP syllabus: not all integrals have exact algebraic solutions, reinforcing the importance of approximation methods and conceptual reasoning about accumulation.

Strategies for Working with Non-Elementary Integrals

When encountering a function without an elementary antiderivative, students rely on alternative approaches. These strategies allow meaningful analysis even without closed-form antiderivatives.

Numerical Integration

Numerical integration provides approximations of definite integrals when symbolic integration fails. Techniques include:

Left Riemann sums

Right Riemann sums

Midpoint sums

Trapezoidal approximation

Though covered elsewhere in the syllabus, these methods become especially important when dealing with integrands lacking elementary antiderivatives.

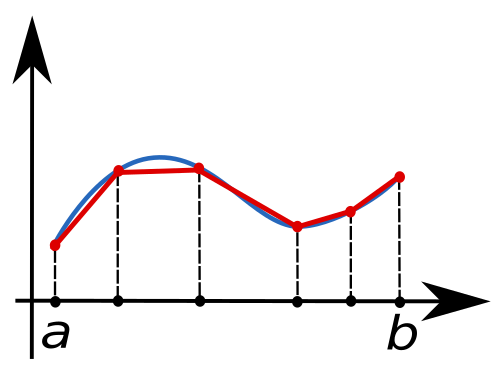

Illustration of the composite trapezoidal rule, where the curve is approximated by adjacent trapezoids. This supports numerical approaches used when symbolic antiderivatives do not exist. The specific curve depicted includes more detail than necessary for AP Calculus AB but serves the same conceptual purpose. Source.

Students should understand that numerical methods can approximate accumulated change to any desired accuracy, given sufficiently refined partitions.

Using Known Special Functions

Some non-elementary integrals give rise to special functions—new function definitions created specifically to represent these integrals.

Special Function: A function defined to represent the value of an integral that has no elementary antiderivative, often arising in mathematical modeling or scientific applications.

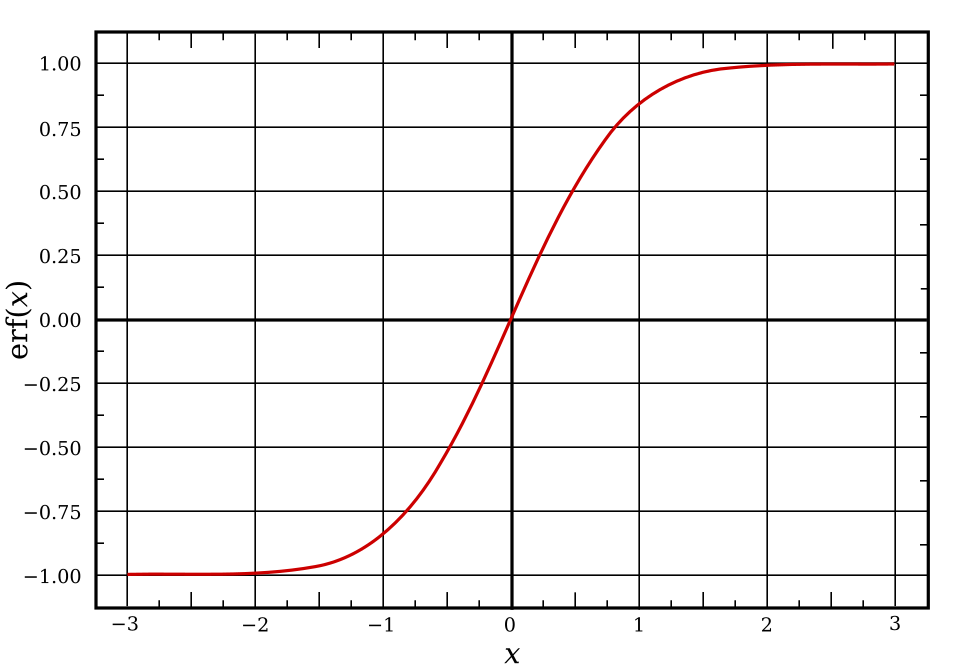

These functions, while beyond the scope of AP Calculus AB in formal use, illustrate how mathematics expands to accommodate new phenomena. For example, the error function erf(x) arises from the integral of e^(-t²), a function known to lack an elementary antiderivative.

Graph of the error function erf(x), which represents accumulated area from the integrand e^(−t²). The curve’s sigmoidal shape and horizontal asymptotes reflect how the accumulation levels off for large values of x. The full interval shown provides additional context beyond AP requirements but remains conceptually aligned. Source.

Understanding that such functions exist helps students grasp why some integrals cannot be expressed in familiar terms.

Series Representations

Another approach is expressing functions as power series in order to integrate term-by-term. Power series are introduced in AP Calculus BC, not AB, but students in AB should still understand that complex integrals sometimes rely on expanding functions into infinite sums.

This reinforces the idea that antiderivatives need not be elementary to be meaningful or useful.

Implications for the Study of Calculus

Recognizing the existence of non-elementary antiderivatives is not a sign of failure in integration but a natural extension of the subject. This awareness helps students:

Avoid wasting time seeking nonexistent closed forms.

Strengthen decision-making about integration techniques.

Appreciate the necessity of numerical methods.

Understand how the concept of accumulation applies even when algebraic expressions fail.

FAQ

Clues often appear when common techniques fail quickly. If standard substitutions make the expression more complicated, or derivatives of component functions do not resemble other parts of the integrand, this is usually a sign that no simple antiderivative exists.

You may also notice that functions formed from nested logs, products of unrelated function families, or unusual compositions commonly fall into this category.

These antiderivatives frequently appear in real scientific models, especially when describing diffusion, wave behaviour, or probability distributions.

Even without closed forms, they define meaningful functions whose properties can be studied using approximations, special function definitions, or qualitative analysis.

Yes. One can study the accumulation function’s behaviour without finding a closed form by examining the sign, continuity, and monotonicity of the integrand.

Graphical or numerical tools also reveal turning points and long-term trends of the accumulation function.

Not always. Sometimes the exam provides a graph or table, removing the need to recognise the function as non-elementary.

Other times, an integral may be presented in a way where students are only expected to interpret or compare values, not compute them exactly.

Yes. A function may be defined using a non-elementary integral but still possess a derivative expressible using familiar functions.

This happens because the derivative of an accumulation function simply returns its integrand, regardless of whether the integrand itself has an elementary antiderivative.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

A function is defined by the integral F(x) = ∫ from 0 to x of e^(t²) dt.

Explain why F does not have an elementary antiderivative and state one method that could be used to approximate F(2).

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

• 1 mark: States that e^(t²) does not have an elementary antiderivative or that no combination of standard functions can express its antiderivative.

• 1 mark: Notes that therefore F cannot be written in closed form using elementary functions.

• 1 mark: Identifies a valid approximation method such as the trapezoidal rule, midpoint rule, or Riemann sums.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Consider the function g(x) = ∫ from 1 to x of (sin t)/t dt.

(a) Explain why the integrand does not have an elementary antiderivative.

(b) Describe how you could obtain an approximate value for g(4) using a numerical method.

(c) Without carrying out any calculations, state how increasing the number of subintervals in your numerical method affects the accuracy of the approximation.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

(a)

• 1 mark: States that (sin t) / t has no elementary antiderivative.

• 1 mark: Provides a reason, such as standard techniques (substitution, algebraic manipulation) do not simplify the integrand.

(b)

• 1 mark: Identifies a correct numerical method (e.g., trapezoidal rule, left or right Riemann sums, midpoint method).

• 1 mark: Describes how the selected method would be applied on the interval from 1 to 4 using subintervals.

(c)

• 1 mark: States that increasing the number of subintervals improves accuracy or reduces error.