AP Syllabus focus:

‘When using substitution for a definite integral, change the limits of integration to match the new variable so the final answer is expressed without back-substitution.’

Changing limits during substitution ensures definite integrals remain consistent with the substituted variable, allowing evaluation entirely in terms of the new expression and preventing unnecessary back-substitution errors.

Understanding Substitution in Definite Integrals

Substitution for definite integrals is closely connected to reversing the chain rule, which allows complex integrands to be rewritten in simpler terms. When performing this process, the essential idea is to transform both the integrand and the limits of integration so the final integral is expressed entirely in the substituted variable. This avoids the need to return to the original variable and maintains clarity about how the limits relate to the transformed expression.

A key component of substitution is the substitution variable , introduced to simplify the integrand. When the substitution is made, the differential and corresponding limits must be updated accordingly. This ensures the integral remains properly defined over the new interval.

Why Changing Limits Matters

When working with definite integrals, the limits specify the exact portion of the curve being accumulated.

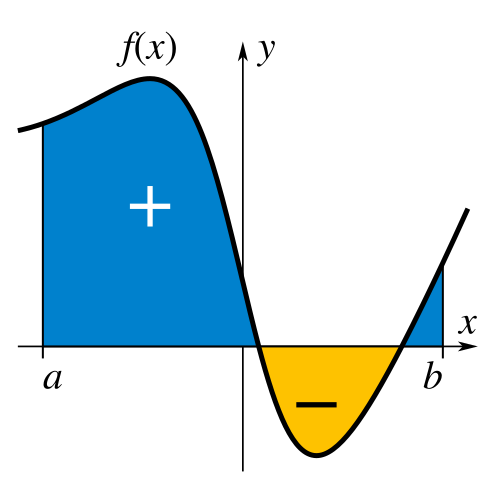

This figure depicts a function and the region whose signed area is represented by a definite integral from to . The shaded region corresponds to the net accumulation of over that interval. The image does not show substitution explicitly, but it represents the area that must be preserved when changing variables and limits. Source.

If a substitution transforms the variable, keeping the original bounds would create a mismatch between the integrand and the interval. Adjusting the limits creates a new, equivalent integral in terms of , preserving the meaning of the definite integral and preventing algebraic inconsistencies.

Changing limits also enhances conceptual understanding, as students see directly how input values in the original variable map into the new variable. This reinforces the importance of connecting rate-of-change behavior with accumulated values.

Identifying the Structure of a Definite Integral Suitable for Substitution

A definite integral is suited for substitution when it features a composite expression, typically matching the structure of the chain rule. Look for:

An inner function whose derivative (or a constant multiple of it) appears elsewhere in the integrand

A clearly identifiable substitution that simplifies the expression

Bounds that correspond directly to values of the original variable

Once the substitution variable is chosen, the limits must be updated by evaluating the substitution expression at both original bounds.

Changing Limits Step-by-Step

Although detailed examples are not included here, the general process for applying substitution with changing limits proceeds through the following structure:

Choose a substitution such that simplifies the integrand.

Differentiate the substitution to express in terms of .

Convert the integral by rewriting the integrand using and .

Update the limits of integration by substituting the original bounds into .

Evaluate the new definite integral using the transformed limits.

Avoid back-substitution, as the updated limits produce a final answer completely in terms of .

These steps maintain consistent relationships between variables while preserving the integrity of definite integration.

Conceptual Meaning of Changing Limits

The limits of a definite integral identify the start and end of the accumulation interval. Under substitution, each bound must be mapped from the original variable to the new one. This mapping ensures that the accumulated quantity represents the same physical or geometric interpretation.

For example, if the original integral measures accumulated change over from to , then the substituted integral measures the same accumulated change but expressed over from to . The transformation does not alter the real-world meaning of the integral; it alters only the variable used to compute it.

This process demonstrates an important conceptual point: changing limits in substitution is not optional, but essential to properly defining the integral in a new variable. Leaving limits unchanged while switching variables introduces contradictions, because the new integrand no longer corresponds to the original input values.

Formalizing Substitution for Definite Integrals

To support clarity, the substitution method for definite integrals can be expressed using a standard mathematical relationship.

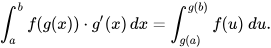

This displayed equation summarizes the substitution rule for definite integrals, converting an integral in to an integral in with bounds and . It highlights that the limits must be expressed in the new variable once the substitution and are used. The notation here is slightly more general than typical AP examples but remains fully compatible with AP Calculus AB expectations. Source.

= original independent variable

= substitution variable defined by

= original limits corresponding to

= transformed limits corresponding to

Changing limits aligns the evaluation process with the new variable while preserving the meaning of accumulation. The substitution variable becomes the primary lens through which the region under the curve is examined, making the evaluation more straightforward.

After expressing the integral in terms of and transforming the limits, the result can be computed without returning to the original variable. This practice keeps the solution aligned with formal calculus techniques and supports precision in multistep integration.

Key Principles for Students

To ensure accuracy when applying substitution in definite integrals, students should keep the following principles in focus:

Always adjust the limits when switching to a new variable.

Avoid back-substituting once limits have been changed.

Confirm that transformed limits match the substituted expression.

Ensure that the substitution simplifies the integrand, not complicates it.

Recognize that definite integrals reflect total accumulated change, which must remain consistent under variable transformations.

These principles support both procedural mastery and deeper conceptual understanding of definite integration with substitution.

FAQ

If you keep the original limits while switching variables, the new integral becomes inconsistent because the integrand and bounds no longer refer to the same variable.

This usually produces an incorrect numerical value, even if the algebraic steps look correct.

To fix this, either convert the limits immediately after substituting or revert fully to the original variable before evaluating.

In definite integrals, changing the limits is usually more efficient because it avoids extra algebra and prevents mistakes when simplifying expressions.

Changing limits is especially helpful when the substitution creates a much simpler integrand, leaving no reason to return to the original variable.

However, if the substitution leads to complicated expressions for the new limits, back-substitution can be a practical alternative.

Yes. Sometimes applying a substitution results in upper and lower limits that appear in reverse order.

When this happens, you can:

• Swap the limits and attach a negative sign, or

• Leave them reversed if you prefer, as long as you evaluate the integral correctly.

This phenomenon is normal and simply reflects how the substitution changes the direction of the interval.

Multiple substitutions are allowed, but each substitution requires its own update of the limits.

To stay organised:

• Change the limits for the first substitution.

• If a second substitution is needed, update the limits again based on the new variable.

This stepwise approach avoids mixing variables and prevents errors caused by reverting to a previous substitution too early.

Changing limits ensures that the resulting integral is fully written in the new variable, allowing the Fundamental Theorem of Calculus to be applied cleanly.

By aligning the integrand and limits in the same variable, the theorem can be used without the added step of back-substituting.

This produces a direct evaluation and reinforces the idea that definite integrals depend only on the endpoints, not on the variable used.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Evaluate the definite integral

∫ from x = 0 to x = 2 of 4x(2x + 3)^5 dx

using the substitution u = 2x + 3.

Give your final answer without converting back to x.

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

• 1 mark for correct substitution u = 2x + 3 and du = 2 dx or dx = du/2.

• 1 mark for correctly changing limits from x-values 0 and 2 to u-values 3 and 7.

• 1 mark for correct evaluation of the resulting integral and giving final answer in terms of u only.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Let F be defined by

F(x) = ∫ from t = 1 to t = x of (t^2 + 1)(3t^2 − 2)^4 dt.

(a) Use the substitution u = 3t^2 − 2 to rewrite F(x) as an integral in terms of u with correctly changed limits.

(b) Hence or otherwise evaluate F(3).

(c) Explain briefly why changing the limits removes the need for back-substitution.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

(a)

• 1 mark for correct substitution u = 3t^2 − 2 and du = 6t dt, or equivalent rearrangement.

• 1 mark for correctly changing the limits: when t = 1, u = 1; when t = x, u = 3x^2 − 2.

• 1 mark for correctly rewriting F(x) as an integral in u.

(b)

• 1 mark for correct substitution of x = 3 into the new limits to obtain an integral from 1 to 25.

• 1 mark for correctly evaluating the integral in u.

(c)

• 1 mark for noting that because the limits are in the new variable, the integral can be evaluated entirely in terms of u without returning to t.