AP Syllabus focus:

‘Euler’s method gives a numerical procedure for approximating a solution to a differential equation by using tangent line slopes to step from one point to the next along a solution curve.’

Euler’s method provides a numerical strategy for approximating solutions to first-order differential equations, using the idea that a curve’s tangent line gives a local linear estimate of its behavior.

Understanding the Idea Behind Euler’s Method

Euler’s method is built on a central insight from differential equations: if a function satisfies a relationship between its value and its rate of change, then using the instantaneous rate of change allows us to predict how the function behaves over a short interval. This process approximates a true solution curve by constructing a sequence of small, stepwise movements guided by tangent line slopes.

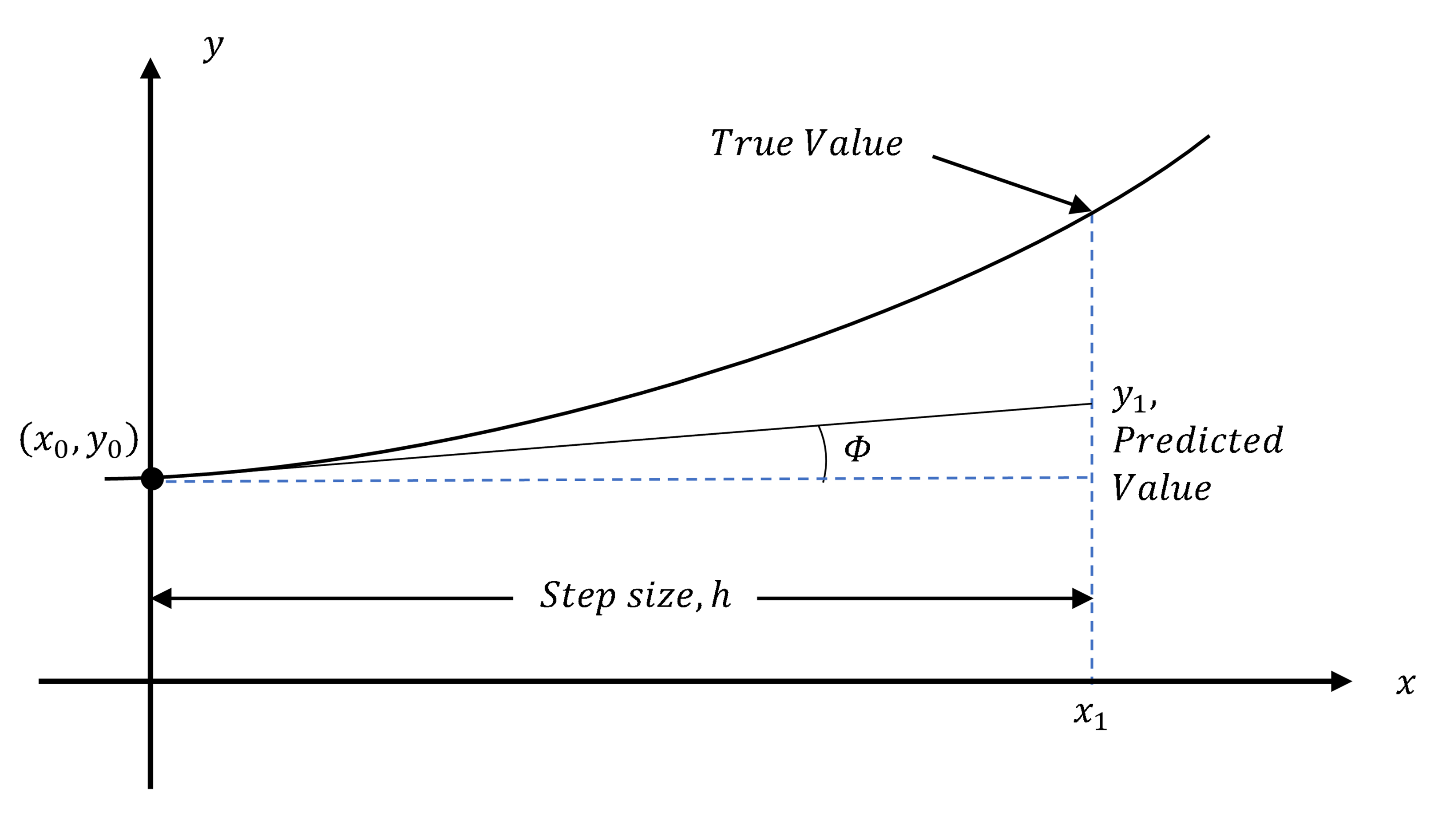

This figure illustrates the first Euler step, using the tangent line at (x0,y0)(x_0,y_0)(x0,y0) to predict the approximate value at x1x_1x1. The step size hhh marks the horizontal distance to the new point. The smooth curve shows the true solution, emphasizing that Euler’s method produces an approximation. Source.

The foundation of Euler’s method is the interpretation of the differential equation as giving the slope of the tangent line to the unknown solution curve at any point. Because the actual solution may be impossible to obtain algebraically, following these slopes provides a way to build an approximate path one segment at a time.

Differential Equations and Tangent Line Approximation

When a differential equation specifies that the derivative provides the slope of the solution curve at every point, it allows us to imagine the graph of the solution as being composed of many short tangent-line segments. The idea behind Euler’s method is to replace the unknown curve with these linear segments, effectively “walking” along the direction of the slope.

Tangent Line Perspective

A tangent line to a differentiable function locally resembles the function itself. Thus, using a tangent line to advance a short distance in the horizontal direction gives a reasonable approximation of the change in the dependent variable. Euler’s method formalizes this intuition by making each step small enough that the cumulative error remains manageable.

The Step-By-Step Movement

Each step in Euler’s method proceeds using the current point, the given slope from the differential equation, and a chosen step size. Students should understand that this method relies entirely on computing successive slopes and updating the dependent variable iteratively. The method works because a differential equation provides slope information everywhere, so each point becomes the starting point for the next linear approximation.

= Current approximate value of the dependent variable

= Updated approximate value after one step

= Step size in the independent variable

= Derivative given by the differential equation, representing slope

Euler’s method uses this update repeatedly, producing a chain of approximate points that trace the behavior of the underlying solution.

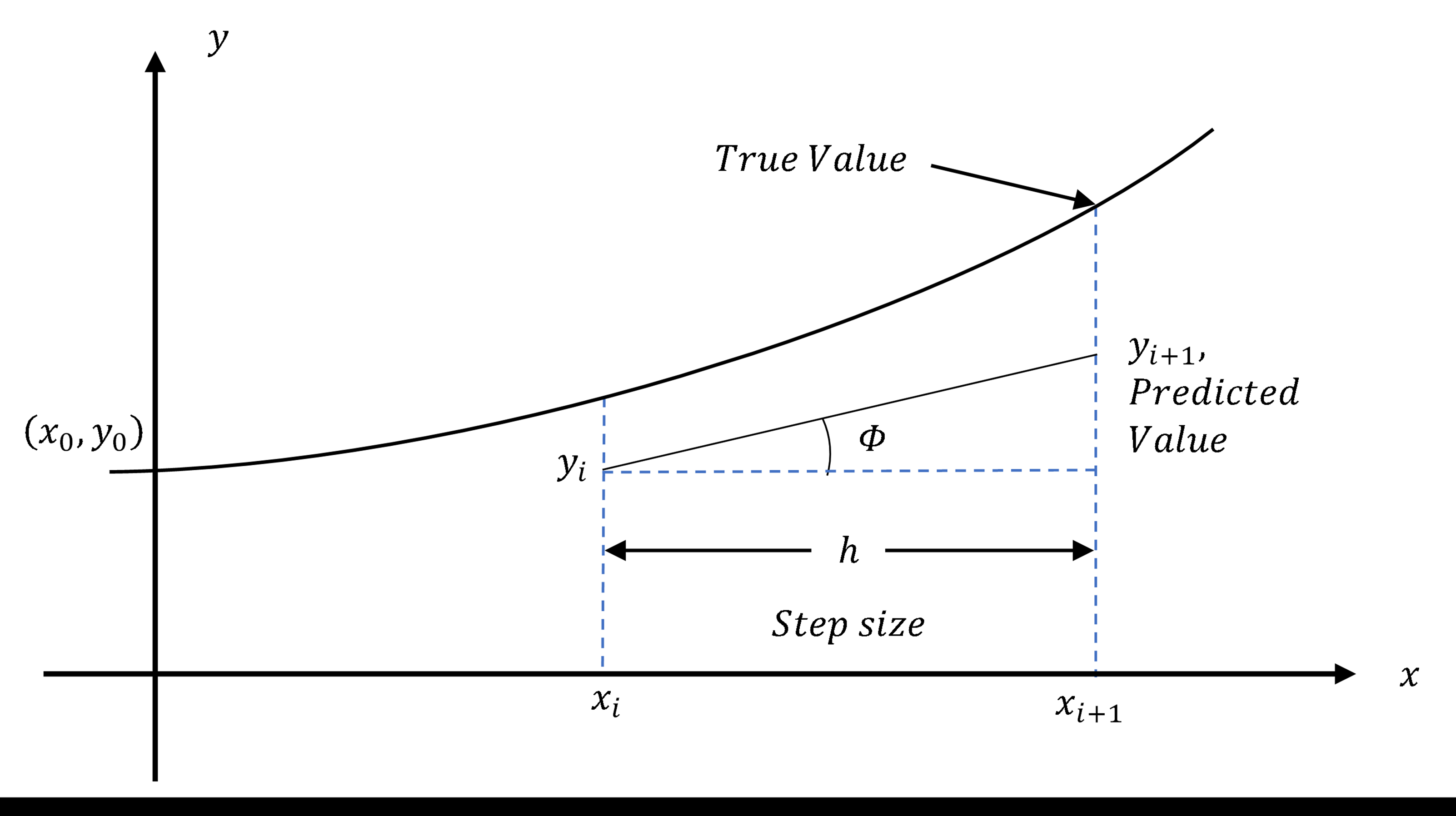

This diagram represents a general Euler step from (xi,yi)(x_i,y_i)(xi,yi) to (xi+1,yi+1)(x_{i+1},y_{i+1})(xi+1,yi+1). The tangent line gives the direction of the update, and the step size hhh determines the horizontal movement. The true curve is included to highlight the approximate nature of the method. Source.

Why Euler’s Method Works Conceptually

The success of Euler’s method depends on interpreting the differential equation as a rule that governs how the solution changes. Because a derivative measures instantaneous rate of change, it tells us the direction in which the function is moving at any specific point. Over a very small interval, the function behaves almost linearly, so applying the derivative as though the graph were a straight line offers a valid approximation.

Building Paths Along the Differential Equation

Using Euler’s method means constructing an approximate trajectory aligned with the differential equation’s slope field. Each Euler step can be visualized as a tiny segment tangent to the expected curve. Through this lens, Euler’s method provides both a conceptual and numerical way to follow the differential equation’s dynamics without solving it analytically.

This diagram compares the exact solution curve (blue) with the polygonal Euler approximation (red). Each red segment represents one Euler update based on the slope at the previous point. The figure suggests that smaller steps would make the polygonal path more closely follow the true curve. Source.

Key Features of Euler’s Method

The Role of Step Size

The step size controls how far the approximation moves at each stage. Shorter steps lead to smaller linearization errors, resulting in a more accurate accumulation of approximations. Larger steps provide quicker computations but may drift significantly from the true solution curve because the tangent line ceases to be a reliable approximation over longer intervals.

The Dependence on the Derivative Function

Euler’s method relies on repeatedly evaluating the derivative function, meaning that the method depends entirely on the accuracy and consistency of this function. Because the differential equation determines slope directly, the method adapts naturally to functions whose rates of change vary widely across the domain.

Predictive Movement from Known Information

The procedure always begins with an initial point that satisfies the differential equation’s context. From this starting point, Euler’s method predicts the next value by using the slope indicated at that specific location. This prediction-based movement continues iteratively, identifying a sequence of approximations that collectively outline the behavior of the actual solution.

Conceptual Importance in AP Calculus AB

Euler’s method reinforces important themes of differential equations: the relationship between a function and its derivative, the interpretation of slope as a rate of change, and the use of local linearity. By grounding numerical approximation in the structure of the differential equation itself, Euler’s method exemplifies how calculus provides tools for modeling change even when explicit solutions remain inaccessible.

FAQ

Euler’s method formalises the tangent line idea by applying it repeatedly with a fixed step size, producing a sequence of calculated points rather than a purely visual sketch.

Hand-drawn tangent approximations rely on estimation and may be inconsistent, whereas Euler’s method uses a systematic, repeatable numeric rule for every step.

Over very small intervals, most smooth functions behave almost linearly because their rate of change does not vary dramatically at that scale.

The tangent line captures the instantaneous direction of motion of the curve, so a short step along this line typically stays close to the true path.

No. Whether Euler’s method overshoots or undershoots depends on the concavity of the actual solution curve relative to the tangent line.

• If the true curve bends above the tangent line, Euler’s method may underestimate.

• If the curve bends below the tangent line, it may overestimate.

The behaviour can change over different intervals of the same problem.

A constant step size keeps the iteration simple and predictable, making it easier to organise computations and compare successive approximations.

Variable step sizes can improve accuracy but require additional rules for when and how to change the step, adding complexity that is usually beyond the scope of introductory methods.

If slopes change gradually across the region, Euler steps tend to stay close to the true curve because the tangent line remains a good local predictor.

However, if the slope field has steep or rapidly varying gradients, even small steps may drift noticeably, as the tangent line becomes less representative of the curve’s behaviour between steps.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

A differential equation is given by dy/dx = 3x − y.

Explain in words the idea behind how Euler’s method would approximate a solution curve starting from a known point.

Question 1

• 1 mark: States that Euler’s method uses the slope given by the differential equation at a known point.

• 1 mark: Explains that a small step is taken in the x-direction using this slope to estimate the new y-value.

• 1 mark: Recognises that repeated steps create an approximate solution curve.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Consider the differential equation dy/dx = x + 2y with an initial point (0, 1).

(a) Describe how a single Euler step of size h would be carried out from this point.

(b) Explain how repeated Euler steps use the structure of the differential equation to create an approximate solution.

(c) State one factor that would improve the accuracy of an Euler approximation and explain why.

Question 2

(a) (2 marks)

• 1 mark: States that the slope is found by substituting the current x and y values into dy/dx = x + 2y.

• 1 mark: States that the new y-value is estimated by adding the slope multiplied by the step size h to the current y-value.

(b) (2 marks)

• 1 mark: Explains that each new point becomes the starting point for the next calculation.

• 1 mark: Recognises that the differential equation supplies the slope at every new point, guiding the iterative approximation.

(c) (1–2 marks)

• 1 mark: States that using a smaller step size increases accuracy.

• 1 mark: Explains this is because the tangent line better matches the curve over shorter intervals.