AP Syllabus focus:

‘To solve a separable differential equation, students rewrite it with dy and dx on opposite sides, then antidifferentiate both sides to obtain an implicit general solution that includes a constant of integration.’

Separating variables provides a structured method for solving differential equations by isolating dependent and independent variable terms, allowing students to integrate each side and derive an implicit general solution.

Separating Variables in First-Order Differential Equations

Separable differential equations form one of the most important families of equations students encounter in AP Calculus AB, because their structure allows direct manipulation into an integrable form. A differential equation is considered separable when its expression for the derivative can be rewritten so that all terms involving the dependent variable appear on one side and all terms involving the independent variable appear on the other. This process leads to a pathway for integrating both sides, ultimately obtaining a general solution containing an arbitrary constant.

When using separation of variables, it is essential to remember that the differential and should be treated symbolically as part of the notation rather than literal quantities. The method works because the derivative represents a ratio of infinitesimal changes, allowing algebraic manipulation under appropriate conditions.

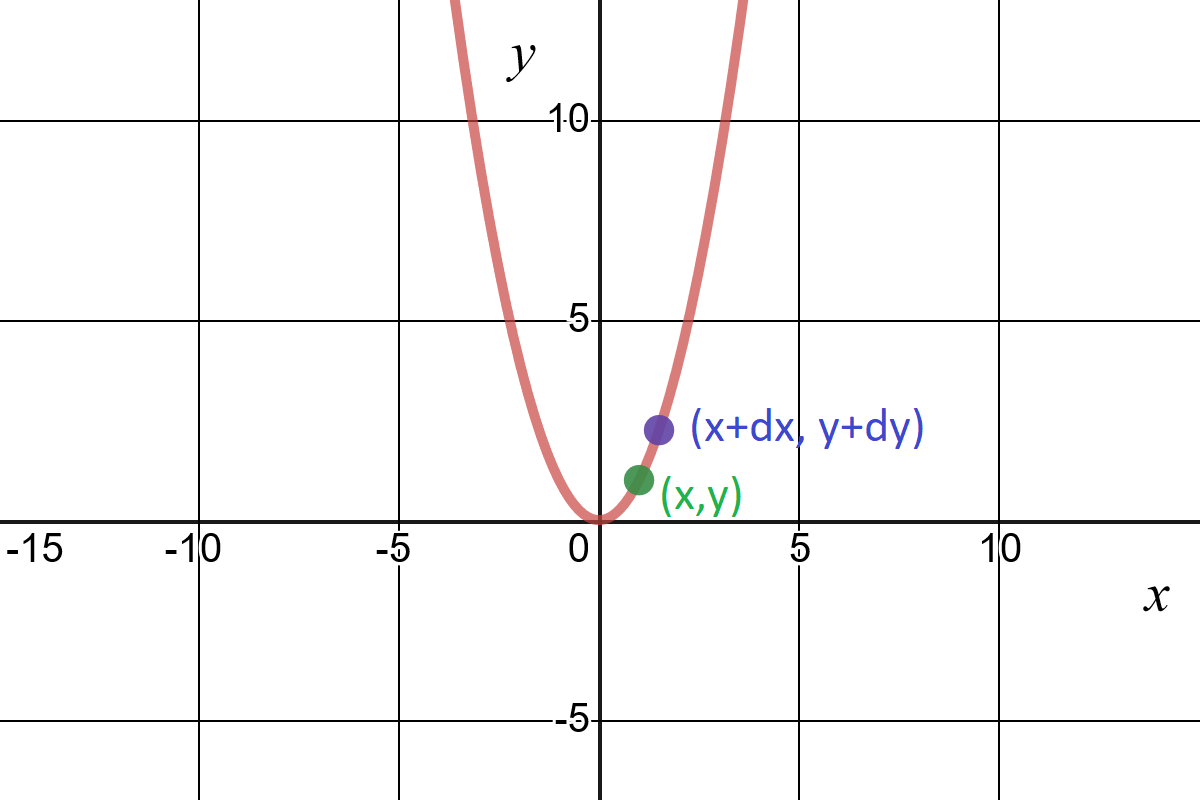

A graph of a parabola illustrates how is a small horizontal change and is the corresponding vertical change, reinforcing the interpretation of as a ratio of infinitesimal changes. The figure visually supports the symbolic manipulation of differentials used in separation of variables. No additional mathematical content beyond the notes is included. Source.

Structure of a Separable Differential Equation

A separable differential equation typically begins in the form , where the rate of change of the dependent variable can be expressed as a product of a function of and a function of . Once recognized, the goal is to isolate the expressions involving and from those involving and .

Separable Differential Equation: A differential equation in which the derivative can be expressed as a product of a function of the independent variable and a function of the dependent variable, allowing the variables to be rearranged on opposite sides for integration.

After recognizing separability, students rewrite the equation by dividing or multiplying to group both -related terms with and both -related terms with . This prepares the equation for the antidifferentiation step.

A typical rearrangement follows this structure:

.

This form ensures that each variable appears only on one side of the equation, creating a clear path to integration.

Integrating Both Sides

Once separation is complete, the next step is to antidifferentiate each side with respect to its variable. This step produces an implicit equation, because the antiderivatives may not naturally solve for the dependent variable.

= Dependent variable representing the unknown function

= Independent variable representing the input to the function

The result of this process is an implicit general solution, which must include a constant of integration to account for the infinitely many solutions satisfying the original differential equation.

Between the integration steps, it is important for students to understand that both sides of the equation represent antiderivatives, and so each side individually would produce its own constant. However, when solving equations of this form, these constants can be combined into a single overall constant added on one side.

Steps in Solving by Separation of Variables

To solve a separable differential equation effectively, students can follow a systematic sequence of steps. This process ensures correct manipulation and integration.

Step 1: Identify separability

The equation must be expressible so that equals a product of a function of and a function of . Students should check that all -related terms can be grouped and all -related terms can be grouped.

Step 2: Rearrange to isolate variables

Students place all values and on one side, and all values and on the other.

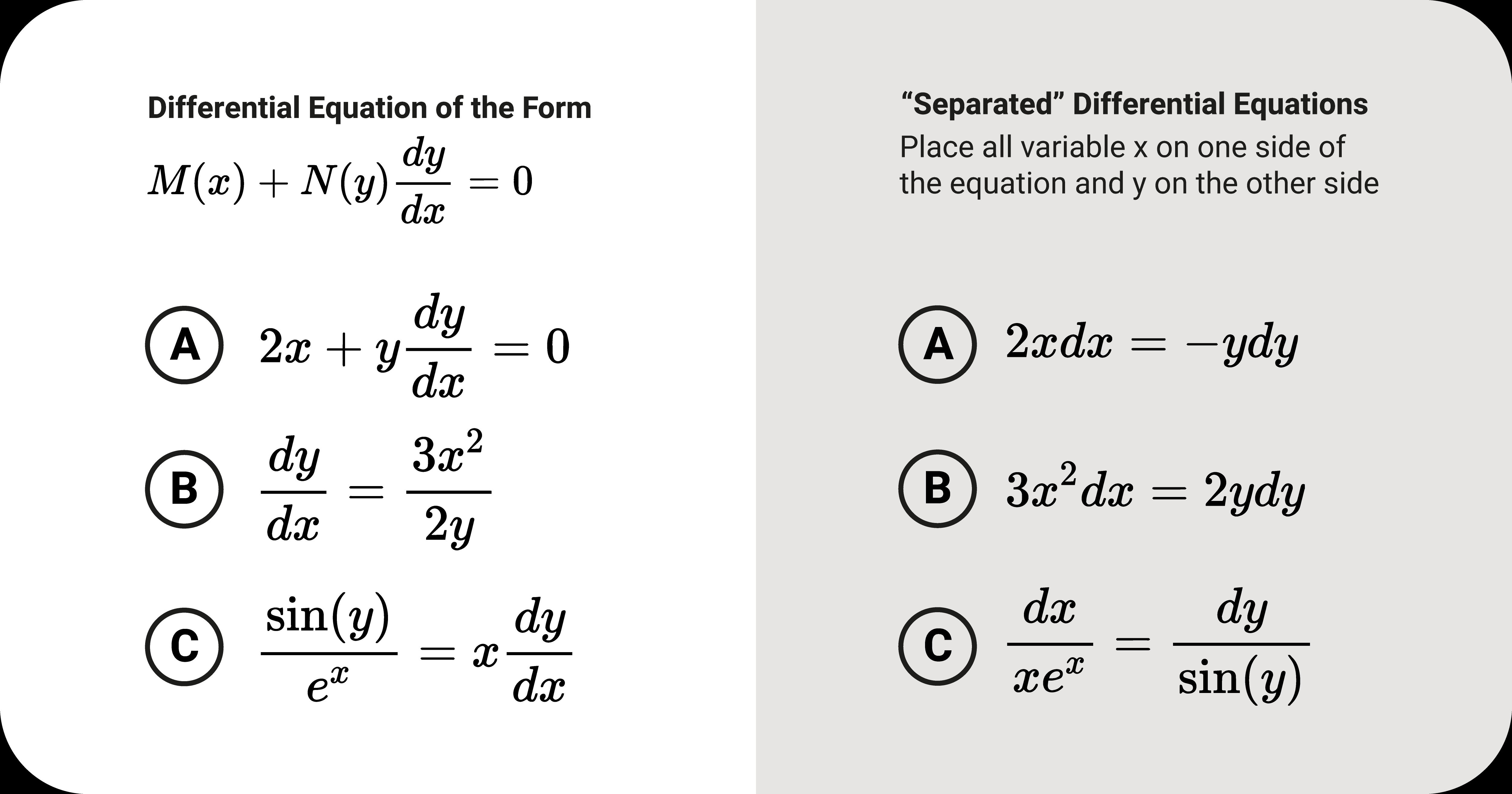

A side-by-side illustration contrasts mixed-variable differential equations with their separated counterparts, highlighting the rearrangement needed so that -dependent and -dependent expressions lie on opposite sides. The image aligns directly with the procedural step described in the notes, though it includes additional example equations that follow the same principle. Source.

Step 3: Integrate both sides

Using standard integration techniques, students antidifferentiate each side with respect to its associated variable. Typical integrals may include power functions, exponential functions, trigonometric functions, or logarithmic expressions depending on the form of the equation.

Step 4: Include the constant of integration

The constant must be included because differential equations describe entire families of solutions. Whether left on the side or within the implicit expression, the constant ensures that all valid solutions are represented.

Step 5: (When possible) Solve for the dependent variable

Though not always required to complete the solution, writing the solution explicitly for can make interpretation easier. Some differential equations, especially those involving logarithmic or exponential relationships, allow relatively straightforward solving for . In cases where isolating is overly complex, the implicit form remains a valid and complete solution.

Importance of the Implicit General Solution

The final implicit solution produced through separation of variables communicates the relationship between the variables without necessarily providing an explicit function. This is acceptable and expected in many cases. Because implicit solutions still satisfy the original differential equation, they serve as the foundation for determining particular solutions once initial conditions are introduced in later subsubtopics.

Through careful manipulation, integration, and interpretation, students see how separable differential equations form a bridge between rate-based models and the functions that satisfy them, reinforcing core calculus ideas about change and accumulation.

FAQ

Separation of variables is justified because the derivative represents a limiting ratio of increments, allowing dy and dx to behave symbolically in manipulations.

A more formal explanation comes from interpreting dy and dx through differential forms, where rearrangement corresponds to multiplying or dividing both sides by appropriate functions.

This symbolic method mirrors a rigorous structure, even though dy and dx are not standalone quantities.

Students often mix variables across sides or forget to move all instances of a variable with its correct differential.

Frequent errors include:

• Leaving a stray y on the x side (or vice versa)

• Failing to factor out functions before dividing

• Neglecting absolute value when integrating reciprocal functions

• Assuming separability when the equation cannot be factored into variable-only components

A quick check is to verify that each side contains only one variable before integrating.

Yes. The method naturally produces an implicit expression because integrals of separated terms rarely isolate the dependent variable immediately.

Students may later solve for the dependent variable explicitly if algebraically feasible.

However, in many realistic settings, the implicit solution is considered complete, particularly when the equation involves logarithmic or inverse trigonometric integrals.

Each side of the separated equation generates its own constant because both represent indefinite integrals.

These constants can be merged because subtracting one from the other still produces an arbitrary constant, just with a different label. Only one constant is necessary to represent the entire family of solutions.

This simplification avoids redundancy and keeps the implicit general solution tidy and interpretable.

Check whether the right-hand side can be written as a product of a function of the independent variable and a function of the dependent variable.

If rearranging produces an expression where all y terms can be grouped with dy and all x terms with dx, the equation is separable.

Common indicators include:

• Expressions like f(x)g(y)

• Rational expressions where numerator and denominator depend on different variables

• Situations where factoring isolates terms by variable

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

A differential equation is given by dy/dx = (3x)(y).

(a) Show how this equation can be rewritten by separating variables.

(b) Write the corresponding integrals that would be used to begin solving the equation.

Question 1

(a)

• Correct separation of variables: dy / y = 3x dx (1 mark)

(b)

• Correct integral setup on both sides:

∫(1/y) dy = ∫3x dx (1 mark)

• Both integrals included and correctly matched to each side (1 mark)

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

A population P satisfies the differential equation dP/dt = kP(5 − P), where k is a positive constant.

(a) Separate the variables to express the equation in the form f(P) dP = g(t) dt.

(b) Write down the integrals required to obtain an implicit solution.

(c) Explain why the constant of integration must be included when finding the general solution.

Question 2

(a)

• Correct rearrangement placing all P terms with dP: dP / [P(5 − P)] = k dt (1 mark)

• Expression shown clearly in separated form (1 mark)

(b)

• Correct integral on the left: ∫ dP / [P(5 − P)] (1 mark)

• Correct integral on the right: ∫ k dt (1 mark)

(c)

• Clear explanation that integration introduces an arbitrary constant because many functions satisfy the same differential equation (1 mark)

• Recognition that the constant is required to represent the family of all general solutions (1 mark)