AP Syllabus focus:

‘Students solve the resulting equation for y when possible and recognize that the arbitrary constant represents a family of general solutions to the differential equation.’

Solving for a function after separation of variables clarifies the structure of differential-equation solutions, revealing how the constant of integration determines an entire family of possible solution curves.

Solving for the Dependent Variable After Integration

Once a separable differential equation has been rewritten with all -terms on one side and all -terms on the other, antidifferentiation produces an implicit general solution. At this stage, the relationship between the variables may still be intertwined. The process of solving for the dependent variable—almost always —allows the solution to be expressed explicitly, which is often more readable and more useful for interpreting behavior. The AP syllabus emphasizes that students should identify when it is feasible to isolate and understand the conceptual significance of the constant of integration in the resulting expression.

Implicit Versus Explicit Forms

An implicit equation expresses a relationship between and without isolating fully. An explicit equation, in contrast, gives as a function of .

This distinction matters because explicit solutions make long-term behavior, comparative growth, or contextual interpretations easier to read directly.

Implicit Solution: A relationship between and obtained after integrating a differential equation in which is not isolated.

A sentence describing context is always helpful before an explicit form is introduced, especially when solving highlights patterns or families of solutions across different constants.

Explicit Solution: A form of a differential-equation solution in which the dependent variable is isolated as a function of the independent variable.

When Solving for Is Possible

Not every implicit solution can be rearranged into a simple expression for . However, many AP-level differential equations—particularly those encountered through separation of variables—lead to functions such as exponentials, logarithms, or polynomial relationships that are straightforward to rewrite explicitly.

Students typically check the following:

• Algebraic isolatability: Whether terms involving can be separated cleanly.

• Function type: Whether the resulting expression can be inverted using familiar functions (exponential, logarithmic, root, polynomial rearrangements).

• Domain constraints: Whether isolating introduces extraneous restrictions or requires selecting between multiple branches (e.g., positive versus negative roots).

A sentence describing the next concept ensures clarity and flow before definitions related to constants are introduced.

The Constant of Integration and Families of Solutions

Every general solution obtained by integrating includes an arbitrary constant, typically denoted . This constant is essential because it represents infinitely many functions that all satisfy the same differential equation. The AP syllabus stresses that students recognize this family structure after solving for .

Constant of Integration: The arbitrary constant added during antidifferentiation that represents all possible antiderivatives and generates a family of solutions to a differential equation.

Meaning and Role of the Constant in the Explicit Form

Solving for often reveals how affects the graph or behavior of the solution. In many cases, the constant determines:

• Vertical shifts, especially in exponential or logarithmic solutions

• Initial output values, linking directly to initial conditions later in the unit

• Family structure, where each constant describes one specific curve among many satisfying the differential equation

Because the constant appears after integration, students must understand that each different value of produces a distinct function, even though all share identical local rate behavior given by the differential equation.

Family of parabolas illustrating how changing a parameter generates many related curves from a single formula. Each curve corresponds to a different value of a constant in , analogous to how an integration constant generates a family of solutions. The parameter here comes from a sequence index rather than directly from integration, but the visual analogy still clearly supports the idea of a one-parameter family of functions. Source.

A sentence after the equation ensures continuity in the discussion and avoids placing two equation blocks consecutively.

Algebraic Implications When Solving for

When isolating , the constant may appear:

• Inside a logarithm or exponential

• As a multiplicative constant after exponentiation

• As part of a factor that shifts the entire family of curves

In each case, the constant of integration still represents the same core idea: multiple possible functions that all satisfy the differential equation before any additional information is applied.

= arbitrary constant determining a specific member of the family

= constant from the differential equation

A sentence after the equation ensures continuity in the discussion and avoids placing two equation blocks consecutively.

Interpreting the Constant Without an Initial Condition

Even before learning how to find a particular solution, students should interpret constants qualitatively. For example:

• Different constants produce parallel solution curves in many exponential families.

• The constant may determine whether a solution is positive, negative, or crosses a particular threshold.

• The presence of the constant ensures that differential equations describe sets of solutions rather than a single unique function.

Importance for Modeling and Future Topics

Understanding how to solve for and interpret the constant of integration prepares students for later topics involving initial conditions, particular solutions, accumulation models, and real-world interpretations. These skills form a foundation for AP Calculus AB’s broader study of differential equations and how they capture patterns of change through families of functions.

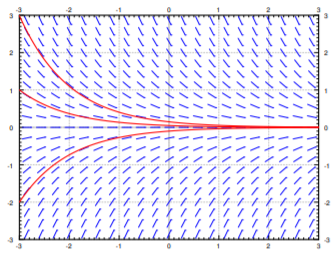

Slope field for with several solution curves superimposed. Each curve follows a shared slope pattern but begins at a distinct initial value, representing different choices of the constant in the general solution . The image includes the added detail of the slope field, which extends beyond the subsubtopic but reinforces the idea of a family of solutions determined by an integration constant. Source.

FAQ

Multiple explicit forms arise when isolating y requires taking a square root or another operation that naturally has two branches.

To identify this:

• Look for even powers of y in the implicit equation.

• Check whether solving introduces a plus–minus choice.

• Consider domain restrictions that may limit which branch is valid in context.

During manipulation, constants often combine with numerical factors or appear inside exponentials or logarithms.

Instead of tracking the original symbol, it is standard practice to replace the transformed expression with a new constant, because:

• Its precise algebraic form is irrelevant.

• It still represents the entire family of solutions.

• It preserves the idea of one arbitrary constant, even after multiple steps.

An explicit form makes it easier to see how y behaves as x increases or decreases.

For example:

• Exponential expressions show growth or decay directly.

• Rational forms reveal asymptotes or boundedness.

• The constant of integration shifts the curve but does not change the basic long-term trend.

After isolating y, examine the expression for possible restrictions.

Key checks include:

• Denominators that could become zero.

• Logarithmic arguments that must remain positive.

• Square roots that require non-negative radicands.

• Whether the original differential equation allows y to cross certain values.

Implicit forms can show structural relationships between variables that get obscured when y is isolated.

For instance:

• Symmetry between x and y may disappear in the explicit version.

• Critical points or special values may be more visible before rearranging.

• The implicit form may reveal constraints that require extra care when interpreting the explicit result.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

A differential equation has the implicit general solution

3y² = 2x + C.

Solve explicitly for y, and state how the constant of integration is represented in your final answer.

Question 1

• 1 mark: Correct algebraic rearrangement leading to y² = (2x + C)/3.

• 1 mark: Correct solution for y as y = ± sqrt((2x + C)/3).

• 1 mark: Clear statement that the constant of integration remains within the expression (inside the square root) and determines the particular member of the family of curves.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

A differential equation has been solved using separation of variables, yielding the implicit general solution

ln(y + 4) = 5x + C.

(a) Solve explicitly for y.

(b) Describe how the constant of integration affects the family of solutions.

(c) Explain why different values of the constant of integration still satisfy the same differential equation.

Question 2

• 1 mark: Exponentiating both sides to obtain y + 4 = K e^(5x), where K is a constant.

• 1 mark: Correct explicit solution y = K e^(5x) − 4.

• 1 mark: Statement that the constant of integration K shifts or rescales the solution curve, producing a family of distinct functions.

• 1 mark: Recognition that each value of the constant corresponds to a different initial condition.

• 1 mark: Explanation that substituting the explicit solution and its derivative into the original differential equation would show all members of the family satisfy it.

• 1 mark: Clear reasoning that the differential equation specifies rate behaviour, which multiple curves can share even though they differ by the constant of integration.