AP Syllabus focus:

‘Solutions to differential equations may have restricted domains, and students consider where the solution formula is defined and consistent with the original differential equation and context.’

Understanding when a solution to a differential equation is mathematically valid requires careful attention to its domain, ensuring consistency with both algebraic expressions and contextual limitations.

Domain Restrictions for Solutions

Solutions to differential equations do not always apply for all real values of the independent variable. Instead, their domain—the set of input values for which the solution is defined—may be limited by algebraic, analytic, or contextual constraints. These restrictions ensure that the solution aligns with the original differential equation, remains mathematically valid, and fits the situation being modeled.

Why Domains Matter in Differential Equations

When solving a differential equation, integration often introduces expressions such as logarithms, radicals, rational functions, or exponentials. Each of these mathematical elements carries inherent restrictions on permissible input values. A solution is only meaningful on intervals where:

The function is defined.

The derivative used in the differential equation is defined.

The relationship between the function and its derivative holds true.

The context of the problem allows the modeled quantity to exist.

For AP Calculus AB, it is essential to recognize that obtaining an explicit or implicit solution is only part of the process; verifying that it is valid on an appropriate domain is equally important.

Identifying Domain Restrictions from Algebraic Expressions

A solution may involve expressions that limit its domain. The most common restrictions arise from:

Denominators that cannot equal zero.

Radicands of even roots that must be non-negative.

Arguments of logarithms that must be positive.

Exponential expressions that must align with given initial conditions.

Domain of a Solution: The set of all input values for which a solution function is defined and for which the original differential equation remains valid.

When such a restriction is identified, the domain typically becomes an interval or collection of intervals excluding problematic values.

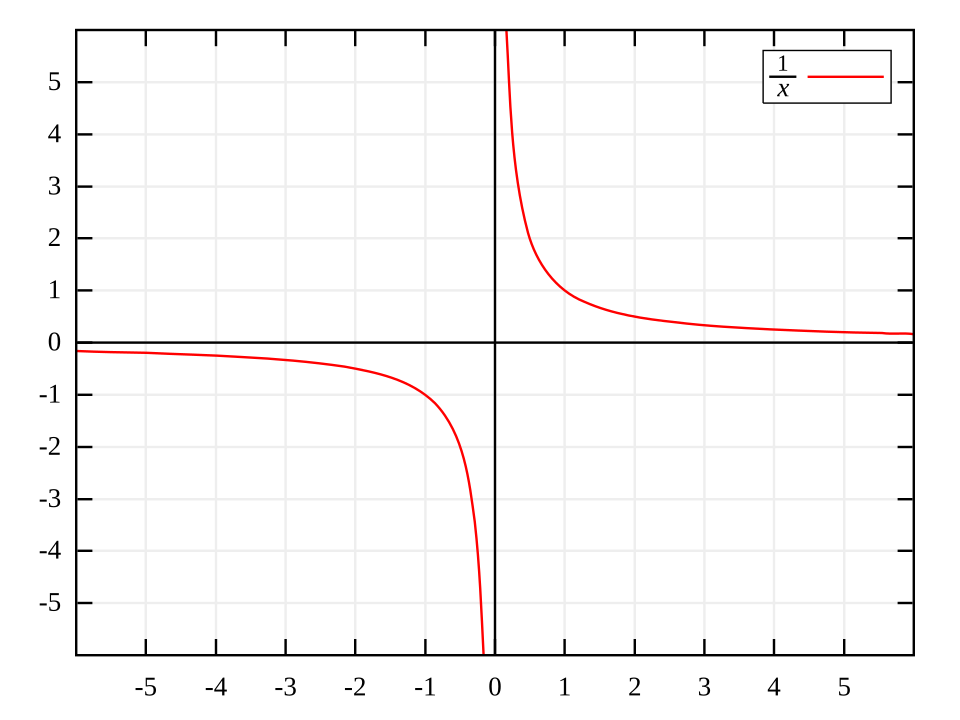

This graph of a reciprocal function, , shows a vertical asymptote at , where the function is undefined. The domain is the union of two intervals on either side of the asymptote, illustrating how excluded -values break the domain into separate pieces. The constant 8 and the precise scale are not important for AP Calculus AB; they simply provide a clear example of a function whose formula forces a domain restriction. Source.

Because differential equations rely on derivatives, any point where the derivative fails to exist or becomes infinite is automatically excluded.

A sentence of normal text is placed here to maintain the required formatting before including an equation block.

= independent variable

= dependent variable

= rate of change determined by the differential equation

This equation indicates that the solution must be defined wherever both and are defined. If is undefined or discontinuous at a point, a solution cannot extend through that point.

Consistency with the Original Differential Equation

Even after solving a differential equation, the solution’s domain must be checked against the original derivative expression. The integration process may produce an expression that appears valid over a wide interval, but the original equation may impose tighter constraints. For instance, a simplified or transformed form may hide discontinuities present before solving.

When considering domain restrictions:

The original differential equation takes priority over the solved expression.

Any value prohibited by the differential equation cannot lie in the domain of the solution.

A solution may be algebraically correct but invalid outside the interval where the differential equation behaves well.

Role of Initial Conditions in Determining Domains

When a particular solution is found using an initial condition, the domain must include the value of the independent variable given by that condition. However, the solution should not be automatically extended beyond nearby intervals without checking for:

Discontinuities in the derivative expression.

Values where the solution formula breaks down.

Context-driven constraints (e.g., negative time values may be meaningless).

Once a point is identified where the solution becomes undefined or inconsistent with the differential equation, the domain should be limited to the maximal interval around the initial condition on which the solution remains valid.

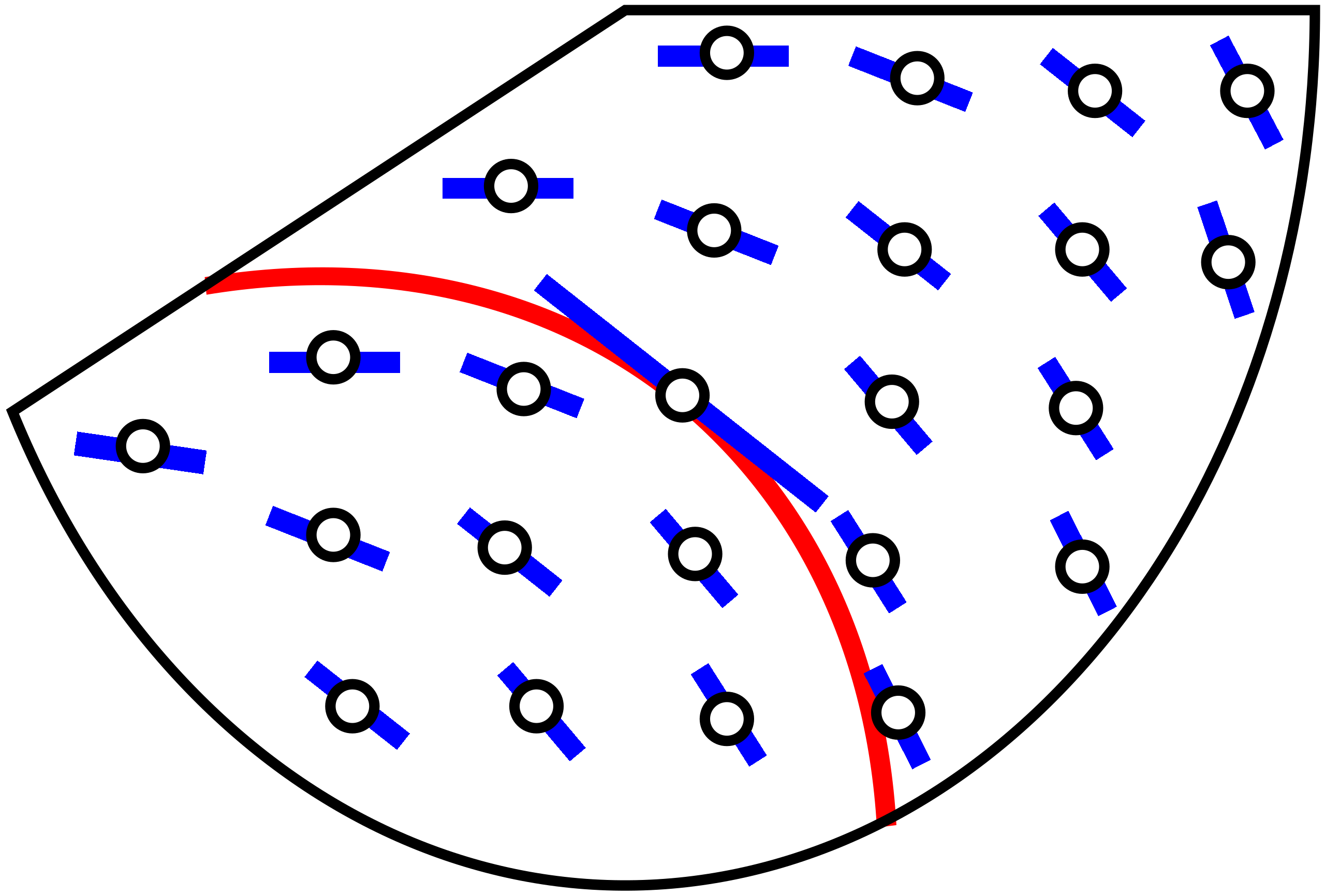

A slope field with a single solution curve illustrates how a particular solution follows the local tangent directions determined by the differential equation. The curve is valid only across the interval where the slope field is defined and smooth, emphasizing the idea of a maximal domain for the solution. The specific differential equation used in this plot is not required by the AP syllabus, but the visual relationship between direction field and solution is directly relevant. Source.

Contextual Domain Restrictions

Many differential equations model real-world quantities, such as populations, temperatures, or velocities. Context may impose additional restrictions beyond mathematics alone. In real scenarios:

Time often begins at a specific moment and cannot be negative.

Physical quantities may need to remain non-negative.

A model may only apply within a window where assumptions remain reasonable.

When interpreting a particular solution, ensuring that its domain matches the real-world situation is essential for meaningful conclusions.

Determining the Valid Domain in Practice

To identify domain restrictions effectively, students should:

Examine the solution expression for algebraic limitations.

Check where the derivative expression in the original differential equation is defined.

Ensure the solution is consistent with the initial condition.

Consider real-world constraints presented in the problem context.

Each of these steps ensures that the solution is both mathematically and contextually appropriate.

FAQ

Domain restrictions determine where a solution curve can be drawn without breaking or jumping. If the differential equation becomes undefined at a certain value, the graph must end before that point.

In practice, this often creates natural boundaries such as vertical asymptotes or gaps in the curve. The complete solution is therefore represented on the maximal interval that avoids the problematic value.

Yes. Even if the general solution is defined on a broad interval, a particular solution may reach a value that makes the original differential equation undefined.

This typically happens when the initial condition places the solution curve closer to a restricted value, such as a denominator approaching zero faster than for other members of the solution family.

The direction in which a solution evolves can influence whether it approaches or moves away from a restricted value.

For some differential equations, solutions on one side of a restriction stay safely away from the undefined point, while solutions on the other side are drawn towards it. The sign of the initial value can therefore determine which interval remains valid.

Yes. Integrating can sometimes hide restrictions that were present in the original differential equation.

For instance, a simplified expression may not show a denominator or root that was originally present. To avoid extending a solution into an invalid region, always check restrictions from the original differential equation, not just the solved expression.

Real-world settings may restrict the domain further than mathematics alone. Time often cannot be negative, and quantities such as mass or population cannot logically fall below zero.

When interpreting solutions, ensure the domain reflects both the mathematical restrictions and the practical limitations of the situation. This helps avoid drawing conclusions that are impossible within the model’s context.

Practice Questions

A function y satisfies the differential equation dy/dx = 3y/(x − 2).

(a) State the value of x that cannot be included in the domain of any solution to this differential equation.

(1 mark)

(a) Correctly identifies that x = 2 cannot be included in the domain.

• 1 mark

A differential equation is given by dy/dx = (x + 1)/(y − 4).

A particular solution passes through the point (0, 6).

(a) Determine the domain of the particular solution with respect to x.

(b) Explain why the solution cannot be extended beyond this domain.

(4–6 marks range)

(a) States that the domain consists of all x-values for which the solution curve does not reach y = 4.

Acceptable answers include:

• The solution is valid on an interval around x = 0 where y remains above 4.

• The domain is the maximal interval for which y does not equal 4.

• 2–3 marks for a clearly described interval or explanation showing understanding of the restriction.

(b) Explains that the solution cannot be extended because the differential equation is undefined when y = 4, creating a vertical asymptote or breakdown in the derivative.

Acceptable elements:

• References the denominator y − 4 becoming zero.

• States that the derivative becomes undefined or infinite.

• Notes that the solution curve cannot cross y = 4.

• 2–3 marks for a clear conceptual explanation.

Total for Question 2: 4–6 marks depending on completeness and clarity.