AP Syllabus focus:

‘Students use an initial condition, usually given as a point on the solution curve, to substitute into a general solution and solve for the constant of integration, producing a unique particular solution.’

Initial conditions allow us to convert a general antiderivative with an arbitrary constant into a unique particular solution that reflects a specific situation described by the differential equation.

Using Initial Conditions to Determine Constants

When solving a first-order differential equation through antidifferentiation or separation of variables, the result is typically a general solution containing an arbitrary constant. This constant represents an entire family of functions that satisfy the differential equation. To identify the single function relevant to a given context, we use an initial condition, which specifies the value of the dependent variable at a particular value of the independent variable.

Understanding the Role of Initial Conditions

An initial condition is a statement that gives one point on the solution curve. It ensures the model aligns with the specific scenario being described. Because many differential equations allow infinitely many antiderivatives, the initial condition selects the only member of the family that passes through the given point.

Initial Condition: A value specifying the dependent variable at a particular independent variable input, typically written as .

The presence of an initial condition links the general mathematical relationship to the physical or contextual situation being modeled, such as population at time zero or velocity at a specific moment.

Structure of General Solutions

When solving a differential equation such as , antidifferentiation produces an expression that includes an arbitrary constant . This constant appears because differentiation removes constant information, leaving an entire family of antiderivatives.

Family of parabolas of the form for various values of the parameter . The curves illustrate how a general solution like represents many possible functions. An initial condition selects exactly one curve from this family. Source.

= Dependent variable

= Independent variable

= Arbitrary constant representing the family of solutions

A single sentence separating blocks: This general form illustrates the need for further information to identify a specific function.

How Initial Conditions Produce a Particular Solution

To move from the general solution to a particular solution, we substitute the values from the initial condition into the general form and solve for . This step anchors the curve to the exact point required by the context.

The Process of Applying an Initial Condition

Students must understand the precise sequence used to determine the constant of integration:

Begin with the general solution obtained from integrating the differential equation.

Substitute the given values of the independent and dependent variables from the initial condition.

Solve the resulting equation for the constant .

Substitute the determined value of back into the general solution to form the particular solution.

Express the resulting function clearly, ensuring it satisfies both the differential equation and the initial condition.

The resulting expression is the unique function that fits the specified situation.

Meaning and Interpretation of the Constant

Although the constant may appear purely algebraic, it has meaningful implications. In many contexts, it encodes initial states such as initial population, initial temperature, or starting position of an object. The value of tells us how the modeled system begins at the designated point and ensures the solution curve reflects that starting state.

Particular Solution: A single function obtained by applying an initial condition to a general solution, producing the unique solution curve that fits the specified scenario.

One sentence between blocks: This definition reinforces how the arbitrary constant is eliminated in order to describe a specific model outcome.

Importance in Mathematical Modeling

Differential equations describe how quantities change, but without initial conditions the descriptions are incomplete. Only after applying the given point do we obtain a solution that corresponds to a real measurement or observed value. In applied settings, the initial condition often represents a baseline measurement, such as the amount of a substance at time zero or the height of fluid in a tank at the start of an experiment.

Common Situations Involving Initial Conditions

In AP Calculus AB contexts, initial conditions are typically provided in one of the following ways:

A statement like “when , ,” written symbolically as .

A contextual description specifying a starting time or initial measurement.

A graph or slope field showing the solution must pass through a particular point.

Across these situations, the purpose remains the same: pin down the correct member of the solution family.

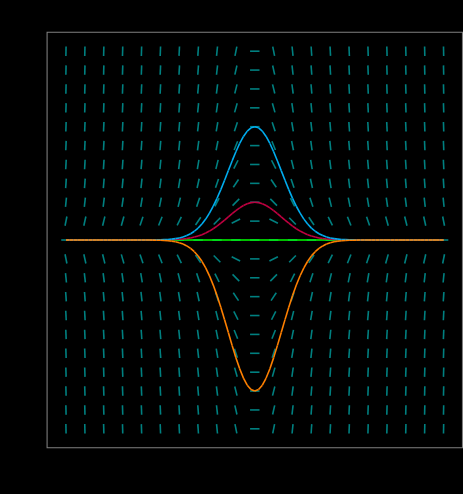

Direction field with multiple solution curves for a first-order differential equation. Each curve shows a different solution corresponding to a different initial condition. Although the diagram contains more detail than required by the syllabus, it clearly illustrates how an initial value selects one unique solution from many. Source.

Ensuring Consistency with the Differential Equation

After determining the particular solution, it is essential to verify that the resulting function satisfies both the differential equation and the initial condition. This reinforces mathematical accuracy and emphasizes the interconnected roles of derivatives, antiderivatives, and conditions supplied by the problem context.

By understanding how initial conditions allow us to determine constants, students gain a clearer view of how differential equations produce meaningful, situation-specific solutions within the framework of AP Calculus AB.

FAQ

You know the initial condition has been fully applied when the arbitrary constant no longer appears in the final expression for the solution. The resulting function should contain only the independent and dependent variables.

You can also check by substituting the initial condition back into the final solution. If it satisfies the given point exactly, the condition has been correctly used.

Yes. If applying the initial condition leads to contradictions, undefined expressions, or results that don’t make sense in the context, the issue usually lies in one of two areas:

• The differential equation might restrict the domain in ways that the initial point violates.

• The chosen antiderivative or algebraic manipulation may have introduced extraneous forms.

In such cases, reconsider the general solution or verify whether the model permits the stated initial condition.

Some general solutions involve squared terms, absolute values, or other expressions that produce more than one algebraic solution for the constant. Both values may be mathematically valid before context is applied.

To select the correct constant, consider:

• Constraints from the situation being modelled.

• Expectations such as positivity, continuity, or physical feasibility.

Translate the contextual statement into a clear point. For example, “the tank initially contains 30 litres at time zero” becomes the point (0, 30).

Ensure you identify:

• Which quantity is dependent.

• The correct units.

• The moment or position at which the measurement is taken.

Once translated into a point, apply it exactly as you would a standard initial condition.

A general solution is suitable if the dependent variable can be evaluated immediately when the independent variable is substituted. If the relationship is implicit or has multiple branches, you may need to rearrange.

Consider rearranging when:

• The expression for the dependent variable contains two or more potential forms.

• Solving for the constant requires isolating the dependent variable first.

• The general solution includes inverse functions or logarithms that introduce different domains.

Once rearranged into a usable form, substitute the initial condition to determine the constant.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

A differential equation has the general solution y = 4x + C. Given that the particular solution passes through the point (2, 11), determine the value of the constant C and state the particular solution.

Question 1

• Correct substitution of the point (2, 11) into y = 4x + C to give 11 = 8 + C – 1 mark

• Correct value C = 3 – 1 mark

• Correct particular solution y = 4x + 3 – 1 mark

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

A population P(t) (in hundreds) satisfies the differential equation dP/dt = 3√P. By separating variables, a student obtains the general solution P = (3t + C)².

(a) Use the initial condition P(0) = 16 to determine the value of C.

(b) Write down the particular solution.

(c) State one reason why an initial condition is necessary when solving a differential equation in a modelling context.

Question 2

(a)

• Correct substitution of t = 0 and P = 16 into P = (3t + C)² to give 16 = C² – 1 mark

• Correct value C = 4 or C = -4, with selection of C = 4 for a positive population – 1 mark

(b)

• Correct particular solution P = (3t + 4)² – 1 mark

(c)

• Correct explanation that an initial condition selects one specific solution from a family of possible solutions – 1 mark

• Clear reference to modelling, for example ensuring the solution reflects the real starting value of the quantity – 1 mark