AP Syllabus focus:

‘For a particle moving along a line, the definite integral of velocity over a time interval gives the particle’s net change in position, or displacement, on that interval.’

Displacement as the Integral of Velocity

This subsubtopic develops the fundamental idea that integrating a velocity function over a time interval yields the particle’s net change in position, helping students interpret motion through accumulated change.

Understanding Displacement Through Accumulated Change

Displacement in rectilinear motion describes how far, and in what direction, a particle moves along a line during a given time interval. Because velocity represents the rate of change of position, integrating velocity over time accumulates all instantaneous position changes, allowing us to measure overall movement. This aligns with the syllabus emphasis that the definite integral of a velocity function gives the particle’s net change in position, not necessarily the total distance traveled.

When we refer to net change in position, we mean the signed change from the starting location to the ending location. Positive velocity contributes positively to displacement, and negative velocity contributes negatively. Thus, the definite integral “adds up” these directional changes.

Connecting Velocity and Position

The relationship between position and velocity provides a natural framework for understanding displacement. Velocity is defined as the derivative of the position function, so integrating velocity returns the change in position. This allows the integral of a velocity function to be interpreted not as an area alone, but as the accumulation of infinitely many small changes in position.

Symbolically, if denotes velocity, the displacement from to is given by the definite integral .

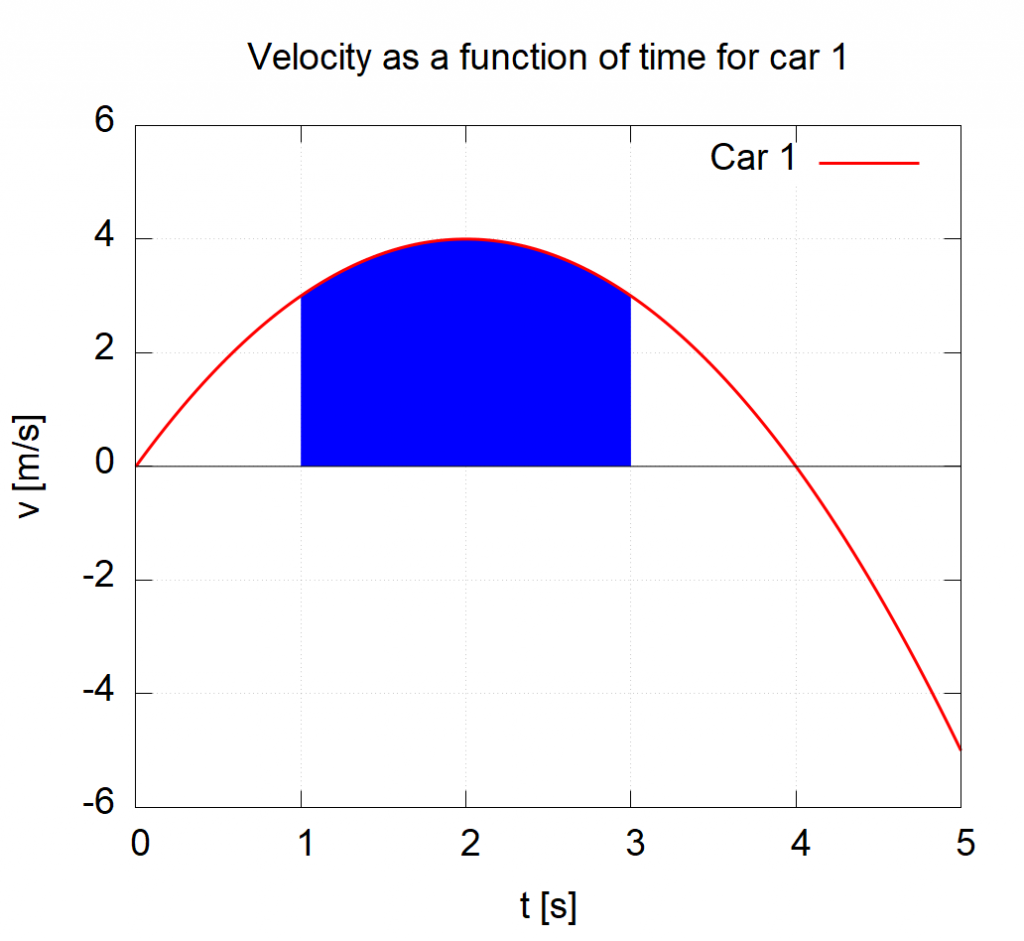

This velocity–time graph for a car shows a smooth red curve above the time axis, with the region between s and s shaded. The shaded area, with units of meters, represents the car’s displacement over that interval. The quadratic expression displayed is extra detail beyond what is required in the AP syllabus. Source.

A definite integral resulting in a positive value indicates net movement in the positive direction, a negative value indicates net movement in the negative direction, and zero displacement means the particle ends where it began, even if it moved along the way.

Interpreting Signed Displacement

Because displacement is a signed quantity, AP Calculus AB students must distinguish it clearly from total distance. The integral of velocity accounts for direction by allowing positive and negative contributions to offset each other. Understanding this makes interpretation of integrals in motion problems more meaningful.

Important ideas related to signed displacement include:

Positive velocity indicates movement in the positive direction.

Negative velocity indicates movement in the opposite direction.

Zero velocity marks moments when the particle stops instantaneously.

Sign changes in velocity correspond to direction reversals in motion.

When analyzing these features, students should carefully consider the behavior of the velocity graph, equation, or table on the given interval.

How the Definite Integral Represents Accumulation

A definite integral represents the limiting sum of the areas of infinitely thin rectangles under a curve. In a motion context, each thin rectangle has a height given by the velocity at that instant and a width representing a tiny change in time. Because velocity measures the instantaneous rate of change of position, each rectangle approximates a small displacement. Summing all such rectangles yields the net change in position.

The following features play central roles in interpreting this accumulation:

The sign of the integrand determines the sign of each small displacement.

The magnitude of velocity determines how quickly position is changing.

The duration of time spent at particular velocities influences the size of the integral.

The definite integral aggregates all changes into one comprehensive measure.

Using Different Representations of Velocity

Students must be skilled at computing and interpreting displacement from a variety of representations of the velocity function, provided they do not involve explicit numerical calculations here. Each representation requires understanding how the integral reflects accumulated change.

When velocity is given:

As a function: Students analyze algebraic expressions and their signs.

As a graph: Students view positive and negative regions visually and interpret areas relative to the axis.

In a table: Students estimate integrals using appropriate numerical methods elsewhere in the course.

For this subsubtopic, the emphasis remains on conceptual understanding rather than procedural estimation.

Key Interpretive Skills for AP Students

To apply displacement as the integral of velocity effectively, students should master several interpretive strategies:

Identify direction of motion by analyzing the sign of the velocity function.

Determine when a particle reverses direction by locating where velocity changes sign.

Describe movement qualitatively using intervals of positive and negative velocity.

Explain the meaning of a definite integral in words, linking it to net change in position over the specified time interval.

Recognize that equal positive and negative contributions can result in zero displacement, despite significant actual movement.

Conceptual Links to Other Motion Ideas

Although this subsubtopic focuses solely on displacement, its concepts support larger ideas in AP Calculus AB. Understanding the integral of velocity as net change forms the basis for interpreting distance traveled, motion modeling, and real-world accumulation problems later in the curriculum. By learning to interpret definite integrals of velocity correctly, students build a foundation for all integral-based motion analysis.

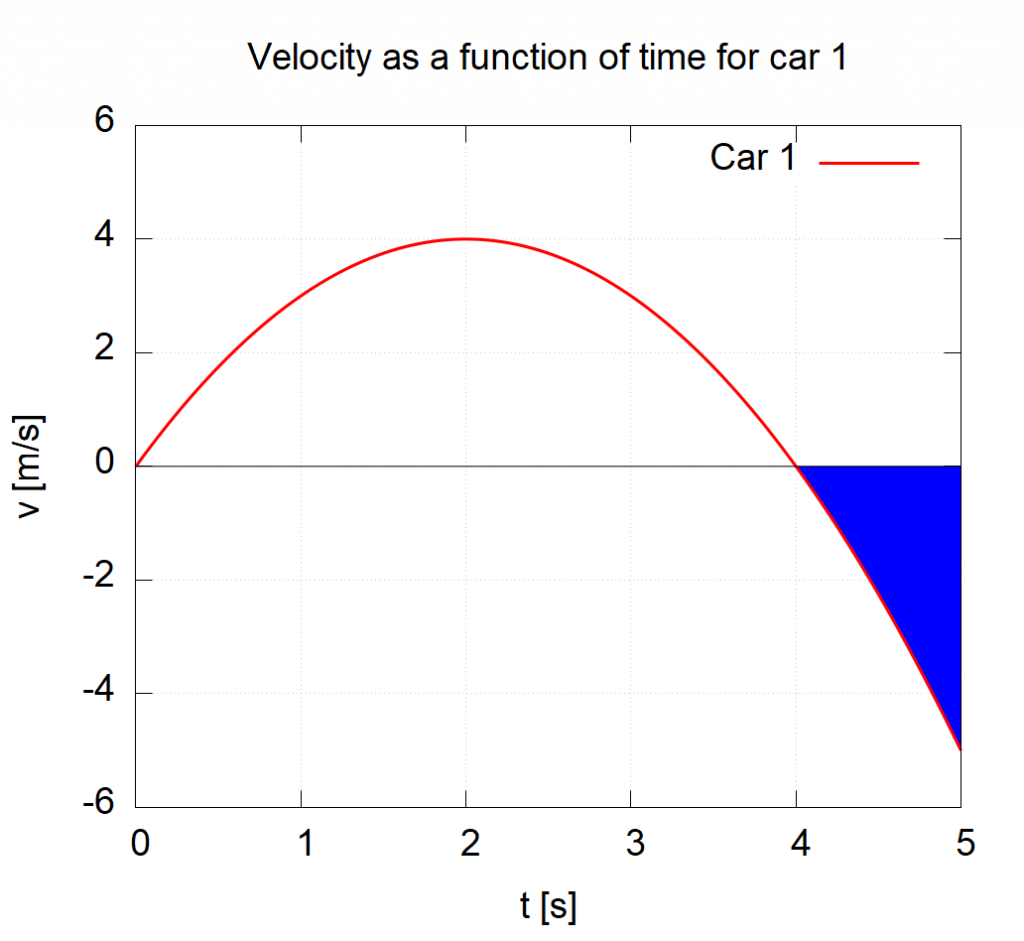

Regions where the velocity graph lies below the time axis contribute negative area to the integral, representing displacement in the negative direction along the line.

In this velocity–time graph, the shaded region lies below the time axis between two times, giving the region a negative area. This negative area represents displacement in the negative direction along the line. The exact numeric values and the quadratic form of shown are additional details not required in the AP curriculum. Source.

FAQ

When velocity changes sign many times, the definite integral effectively combines all small positive and negative contributions to produce a single net change in position.

To interpret such motion more clearly:

• Identify intervals where velocity is positive or negative.

• Consider whether positive or negative areas dominate.

• Recognise that large oscillations may result in a small net displacement even if the particle travels a long distance overall.

Zero displacement means only that the particle ends where it started; it does not describe the path taken.

The particle might have:

• Moved in the positive direction for some time, then back equally far.

• Oscillated around the starting point multiple times.

Displacement summarises final position relative to the start, not the total movement.

Units determine the physical meaning of the integral’s output. If velocity is measured in metres per second and time in seconds, displacement is in metres.

Changing units affects interpretation:

• Kilometres per hour would give displacement in kilometres.

• Mixed or inconsistent units can produce meaningless results.

Always ensure consistency before integrating velocity.

Yes. Displacement remains the signed area between the velocity graph and the time axis, even when the graph is piecewise or has corners.

In such cases:

• Compute the area of each piece separately.

• Apply signs based on whether the graph is above or below the axis.

• Add all contributions to obtain total displacement.

When velocity crosses zero, the particle changes direction instantaneously. At that moment, the contribution to displacement pauses.

Key points:

• A zero of velocity marks the transition between positive and negative motion.

• The integral accumulates positive area before the zero and negative area after, or vice versa.

• The precise timing of the zero can significantly influence the overall sign of displacement.

Practice Questions

A particle moves along a straight line with velocity v(t), measured in metres per second. Over the interval 0 ≤ t ≤ 4, the velocity is positive. Explain what the definite integral from 0 to 4 of v(t) dt represents for the motion of the particle.

(1–3 marks total)

• 1 mark: States that the integral gives the net change in position.

• 1 mark: Recognises that it represents the particle’s displacement.

• 1 mark: Mentions that because velocity is positive on the interval, the displacement equals the total distance travelled.

A particle moves along a line with velocity given by v(t) = t² − 4t + 3, where t is measured in seconds and v(t) in metres per second.

(a) Determine the displacement of the particle over the interval 0 ≤ t ≤ 3.

(b) Determine all times in the interval 0 ≤ t ≤ 3 at which the particle changes direction.

(c) Using your results, explain whether the particle ends to the left or to the right of its starting position, and justify your answer.

(4–6 marks total)

(a) (2 marks)

• 1 mark: Attempts correct integration of t² − 4t + 3.

• 1 mark: Correct evaluation of the definite integral from 0 to 3.

(b) (2 marks)

• 1 mark: Sets v(t) = 0 to find direction changes.

• 1 mark: Correctly identifies the solutions for t and selects values within the interval 0 ≤ t ≤ 3.

(c) (2 marks)

• 1 mark: States whether final displacement is positive or negative.

• 1 mark: Justifies the conclusion using the sign of v(t) or the computed displacement.