AP Syllabus focus:

‘In rectilinear motion, a position function describes a particle’s location along a line, and its rate of change describes velocity over time; definite integrals accumulate these changes.’

Rectilinear motion examines how an object moves along a straight line, using functions to describe its changing position, and applying calculus to connect displacement, velocity, and accumulated change.

Position Functions in Rectilinear Motion

Rectilinear motion involves the study of objects moving along a straight path, where their changing location can be modeled using a position function. The position function, commonly written as or , assigns each time value to a unique location along a one-dimensional axis.

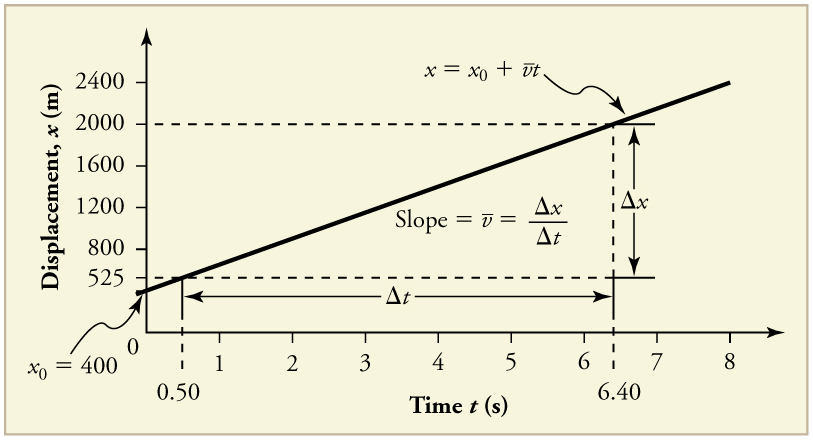

This graph shows displacement on the vertical axis and time on the horizontal axis, modeling a particle moving along a straight line with nearly constant velocity. The straight line illustrates that the position function changes at a constant rate, so the slope of the graph equals the particle’s velocity. This image includes the specific context of a jet car, but the underlying position–time relationship is identical for any rectilinear motion. Source.

When the term position function first appears, students must understand that it is a function giving the particle’s location relative to a chosen origin.

Position Function: A function that assigns the location of a particle on a straight line at each moment in time.

The position function is the foundation of rectilinear motion because every other motion quantity—velocity, acceleration, displacement—derives from it.

The top panel shows vertical position vs. time, the middle panel shows velocity vs. time, and the bottom panel shows acceleration vs. time for a rock moving straight up and down. The changing slope of the position graph matches the values on the velocity graph, illustrating that velocity is the derivative of the position function, while the constant negative acceleration reflects gravitational acceleration. The image includes explicit numerical values and a free-fall scenario, which go beyond the syllabus, but the relationships among the graphs directly support rectilinear motion concepts. Source.

A clear interpretation of this function helps students connect graphical, numerical, and symbolic descriptions of particle movement.

Between definition and equations we include a sentence as required. The position function’s behavior over time allows us to analyze motion qualitatively and quantitatively, including how far an object has traveled and whether it is moving forward or backward.

Rates of Change and Velocity

Velocity describes how quickly and in what direction the particle’s position changes. For rectilinear motion, velocity is defined as the derivative of the position function. This captures the instantaneous rate of change rather than an average change over an interval.

= instantaneous velocity at time

= position function in units of length

Velocity, being signed, distinguishes motion in the positive direction from motion in the negative direction. Positive velocity corresponds to movement to the right (or upward, depending on context), while negative velocity indicates motion to the left.

A sentence between blocks ensures clarity. Students should recognize that the sign of velocity offers immediate qualitative insight into how the particle is moving along the line.

Interpreting Motion from Velocity

Once velocity is understood as a derivative, students can examine its behavior to make statements about the motion. Important ideas include:

If , the particle moves in the positive direction.

If , the particle moves in the negative direction.

If , the particle is momentarily at rest.

Changes in the sign of velocity indicate turning points in the motion.

These interpretations allow students to translate derivative information into concrete physical behavior.

Definite Integrals and Accumulated Change

The syllabus emphasizes that definite integrals accumulate changes in position. When velocity is integrated over time, the total change in the position function is obtained.

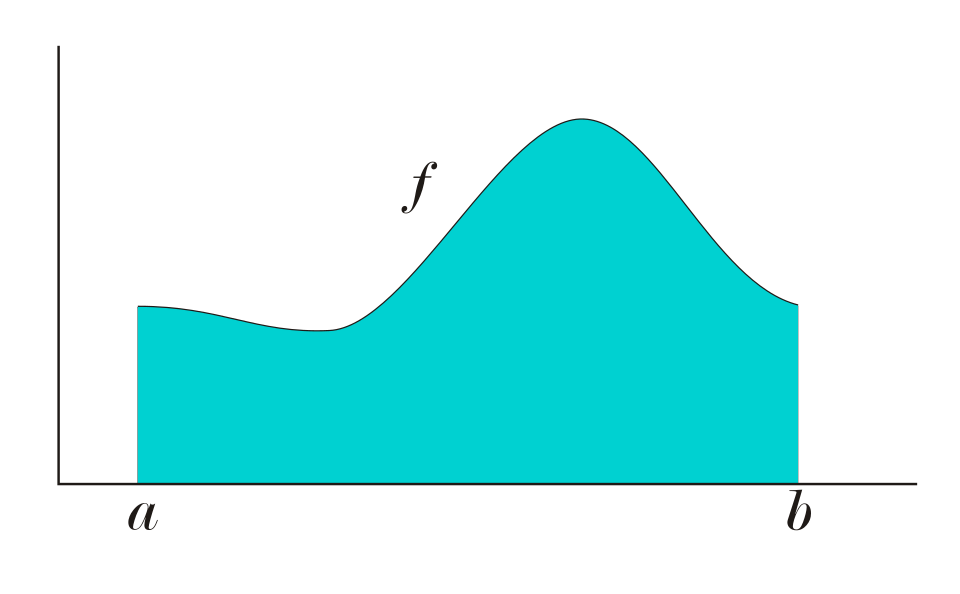

This graph shows a positive function with the area under the curve shaded between two bounds, representing accumulated change over an interval. In calculus, this area corresponds to the definite integral , which models accumulation. Although the curve is generic, students may interpret as to see how integrating velocity over time yields displacement in rectilinear motion. Source.

This accumulated value is known as displacement, which measures the net movement of the particle.

Displacement: The net change in a particle’s position over an interval, accounting for direction of motion.

A sentence between definition and equation keeps the structure correct. Because displacement captures net change, it may be smaller than the total distance traveled when back-and-forth movement occurs.

= velocity function

= time interval in seconds

One sentence must separate equation blocks. This integral expresses the idea that continuously summing infinitesimal changes in position yields the overall shift from the starting point to the ending point.

Using Position Functions with Integrals

Position functions and definite integrals work together to describe motion with accuracy. Students should understand:

The position function gives the exact location of the particle at any time.

The derivative of position gives velocity, revealing instantaneous motion.

The integral of velocity gives accumulated change, describing how far the particle’s position has shifted.

These relationships form the core framework for analyzing motion in AP Calculus AB and enable students to interpret mathematical representations—graphs, tables, formulas—in terms of physical movement.

FAQ

A change in direction occurs when the slope of the position graph changes sign. A positive slope indicates motion in the positive direction, while a negative slope indicates motion in the opposite direction.

You can identify a turning point by locating where the graph has a local maximum or minimum. At such points, the slope is zero, and the particle momentarily stops before reversing direction.

In one-dimensional motion, velocity conveys both speed and direction. The sign distinguishes whether the particle moves along the positive or negative orientation of the line.

This allows us to interpret motion even without a diagram:

• A positive velocity means the particle moves forward.

• A negative velocity means the particle moves backward.

• A zero velocity indicates an instant of rest.

The height of the velocity graph above or below the time axis indicates how the position function changes.

Key observations include:

• Where the graph is positive, the position increases.

• Where it is negative, the position decreases.

• Steeper sections correspond to faster changes in position.

• Zeros of the velocity graph mark moments when the particle is stationary.

Yes. Displacement measures net change in position, not total distance travelled. If the particle returns to its starting point, its displacement is zero regardless of how far it moved in between.

For example, moving 5 metres forward and 5 metres back yields a displacement of zero but a total distance travelled of 10 metres.

Areas above and below the axis represent positive and negative contributions to displacement.

• Area above the axis increases displacement in the positive direction.

• Area below the axis decreases displacement, representing motion in the negative direction.

• The definite integral combines these areas to produce the net displacement over an interval.

This helps explain why the particle may move significantly yet end up close to, or exactly at, its starting position.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

A particle moves along a straight line with position given by the function s(t), where t is measured in seconds and s(t) is measured in metres. At time t = 2, the velocity of the particle is 3 m/s.

State what the value s'(2) = 3 represents in the context of the particle’s motion.

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

• 1 mark: States that s'(2) represents the instantaneous velocity of the particle at time t = 2.

• 1 mark: States the numerical value meaning, i.e., the particle is moving at 3 metres per second at that instant.

• 1 mark: Includes direction: the positive value means the particle is moving in the positive direction along the line.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

A particle moves along a horizontal line, and its velocity v(t), in metres per second, is shown in the table below.

t (seconds): 0 1 2 3

v(t) (m/s): 4 2 -1 -3

(a) Estimate the particle’s displacement over the interval 0 ≤ t ≤ 3 using a trapezium (trapezoidal) rule based on the table.

(b) Determine whether the particle is moving in the positive or negative direction at t = 2 and justify your answer.

(c) Explain what the sign of your answer in part (a) indicates about the particle’s motion.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

(a) Displacement estimate (2–3 marks)

• 1 mark: Correct use of trapezium rule structure:

0.5 × (interval width) × (sum of first and last velocities + 2 × sum of interior velocities).

• 1 mark: Correct substitution:

0.5 × 1 × (4 + (-3) + 2 × (2 + (-1))).

• 1 mark: Correct final answer: displacement = 1 metre (accept 1 or 1.0).

(b) Direction at t = 2 (1 mark)

• 1 mark: States that v(2) = –1 m/s, so the particle is moving in the negative direction.

(c) Interpretation of sign of displacement (1–2 marks)

• 1 mark: States that the positive displacement indicates a net movement to the right (positive direction).

• 1 mark: Recognises this despite negative velocities occurring later, meaning forward motion initially outweighs backward motion.